Macau Hits the Jackpot

In just four years, this 11-square-mile outpost on the coast of China eclipsed Las Vegas as gambling’s world capital

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/macau_sept08_631.jpg)

It's Saturday night and jet foils are pulling into Macau's ferry terminal every 15 minutes, bearing crowds from Hong Kong and the Chinese city of Shenzhen, each about 40 miles distant. A mile to the north, arrivals by land elbow their way toward customs checkpoints in a hall longer than two football fields. By 9 o'clock, visitors will arrive at the rate of some 16,000 an hour. They carry pockets full of cash and very little luggage. Most will stay one day or less. They will spend almost every minute in one of Macau's 29 casinos.

On their way to the hospitality buses that provide round-the-clock transit to the casinos, few of the land travelers will give more than a glance to a modest stone arch built in 1870 by the Portuguese, who administered Macau for almost 450 years.

Outside the two-year-old Wynn Macau casino, a bus pulls up by an artificial lake roiling with bursts of flame and spouting fountains. The passengers exit to the strains of "Luck Be a Lady Tonight." But inside, the Vegas influence wanes. There are no lounge singers or comedians, and the refreshment consists mainly of mango nectar and lemonade served by middle-aged women in brown pantsuits. Here, gambling rules.

This 11-square-mile outpost on the Pearl River Delta is the only entity on the Chinese mainland where gambling is legal. And now, almost ten years after shedding its status as a vestige of Portugal's colonial past and re-entering China's orbit, Macau is winning big. "In 2006 Macau surpassed Las Vegas as the biggest gaming city in the world," says Ian Coughlan, Wynn Macau president. "More than $10.5 billion was wagered [last year], and that's just the tip of the iceberg."

Coughlan is guiding me past rooms with silk damask wallcoverings, hand-tufted carpets and taciturn guards. "Here's our Chairman's Salon," he says. "The minimum bet here is 10,000 Hong Kong dollars [about $1,300 U.S.], so it's very exclusive gaming." But the 25th-floor Sky Casino is his favorite. "It's for people who can afford to lose a million dollars over a 24-hour period," he confides. "God bless them all."

I first visited Macau 30 years ago to report on criminal gangs called triads, then responsible for much of the city's violent crime and loan-sharking. Brightly painted shops that once served as brothels ran the length of Rua da Felicidade in the old port district. Around the corner, on Travessa do Ópio, stood an abandoned factory that had processed opium for China. A mansion built by British merchants early in the 19th century was still standing, as was the grotto where in 1556 Portuguese poet Luis de Camões is said to have begun Os Lusiadas, an epic tale of Vasco da Gama's explorations of the East.

In 1978, residents described the place as "sleepy"; its only exports were fish and firecrackers. Four years earlier, Portugal had walked away from its territories in Angola, Mozambique and East Timor and by 1978, was trying to extricate itself from Macau as well. Secret negotiations concluded in 1979 with an agreement stipulating that Macau was a Chinese territory "under Portuguese administration"—meaning that Portugal relinquished the sovereignty it seized after the Opium War in the 1840s but would run the city for 20 more years. The Portuguese civil servants, army officers and clergy then living there seemed content to take long lunches and allow their enclave to drift.

The police, who wore trench coats and rolled their own cigarettes, allowed me to tag along on what was described as a major triad sweep. But after several desultory inspections of brothels (more discreetly run than their Rua da Felicidade forerunners), they grew tired of the game and headed for the Lisboa Casino, a seedy, threadbare place where men in stained singlets placed bets alongside chain-smoking Chinese prostitutes.

The Lisboa belonged to Stanley Ho, the richest man in town thanks to a government-sanctioned gambling monopoly and his control of the ferries linking Macau to the outside world. But the Macau police showed little interest in Ho, and police officers were barred from frequenting his 11 casinos. So after a quick look around, Macau chief of security Capitão Antonio Manuel Salavessa da Costa and I headed for a drink at a nightclub.

"We can't do anything here," he sighed, looking about the room. "In Macau today the triads are out of control because they're getting into legal businesses. That guy over there is here to protect the place. Those four near the band are his soldiers."

Macau's prospects changed little over the next two decades. Despite Ho's casinos, visitors numbered about 7 million a year to Hong Kong's 11.3 million in 1999. Almost half the hotel rooms were empty. Gangland murders occurred with numbing regularity. For much of that time, Macau's gross domestic product grew more slowly than Malawi's.

But in 1999, the year Portugal formally handed administration of Macau back to the Chinese, the city became a "special administrative region," like Hong Kong after the British turned it over two years earlier. The designation is part of China's policy of "one country, two systems," under which it allows the newly reunited entities autonomy over their own affairs, except in foreign policy and national defense. In 2002, the new Macau government ended Ho's 40-year gambling monopoly and allowed five outside concessionaires, three of them American, to build competing resorts and casinos that would both reflect—and accommodate—China's growing wealth and power. Beijing also made it easier for mainland Chinese to enter Macau.

"China wanted Macau to have growth, stability, American management standards and an international appreciation of quality," says the director of the city's Gaming Inspection & Coordination Bureau, Manuel Joaquim das Neves, who, like many Macanese, has Asian features and a Portuguese name. "Beijing also wanted to show Taiwan that it is possible to prosper under the Chinese flag."

When the Sands casino opened in 2004, the first foreign operation to do so, more than 20,000 Chinese tourists were waiting outside. Stanley Ho—who rarely gives interviews and whose office did not respond to a request for one for this article—was not amused. "We are Chinese, and we will not be disgraced," he was quoted as saying at the time. "We will not lose to the intruders."

The newcomers set the bar high. A mere 12 months after opening the Sands Macau, the Las Vegas Sands Corp. had recouped its $265 million investment and was building a grander emporium, the Venetian Casino and Resort Hotel. At 10.5 million square feet, the $2.4 billion complex was the largest building in area in the world when it opened in 2007 (a new terminal at Beijing's airport surpassed it this year). Its 550,000-square-foot casino is three times larger than Las Vegas' biggest.

This year, Macau is on track to draw more than 30 million tourists—about as many as Hong Kong. At one point, so many mainland Chinese were exchanging their yuan for Macanese patacas that banks had to place an emergency order for more coins.

Macau's casino revenues for 2008 are expected to be 13.5 billion, 30 percent more than last year. By 2012, they are projected to outstrip the revenues of Atlantic City and the state of Nevada combined. With a population of just 531,000, Macau now has a GDP of more than $36,000 per capita, making it the wealthiest city in Asia and the 20th-richest economy in the world. Says Philip Wang, MGM's president for international marketing: "It took 50 years to build Las Vegas, and this little enclave surpassed it in four."

And it did so despite its unusual relationship with China's communist rulers—or, perhaps, because of the rulers' unusual relationship with capitalism. On one hand, the Chinese government is so hostile to gambling that it prohibits Macau casinos from advertising even their existence in Chinese media. On the other, having such a juggernaut on its shores serves China's development goals. (All casino taxes—35 percent of gross revenue, plus 4 percent in charitable contributions—go to Macau.) Says MGM Mirage International CEO Bob Moon: "We're working with China to move the Macau business model beyond day-tripping gamblers to that of an international destination that attracts sophisticated travelers from the four corners of Asia."

This modern magnet was once called "The City of the Name of God in China, No Other More Loyal," at least by the Portuguese, after Ming dynasty Emperor Shizong allowed them to set up an outpost here in 1557. Jesuit and Dominican missionaries arrived to spread the Gospel, and merchants and sailors followed. Macau quickly became a vital cog in the Portuguese mercantile network that reached from Goa, on India's Malabar Coast, to Malacca, on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, to the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

The Jesuits opened the College of Madre de Deus in 1594 and attracted scholars throughout Asia. By 1610, there were 150,000 Christians in China, and Macau was a city of mansions, with Portuguese on the hills and Chinese living below. Japanese, Indians and Malays lived beside Chinese, Portuguese and Bantu slaves, and they all rallied to defeat the Dutch when they tried to invade in 1622. There was little ethnic tension, partly because of intermarriage and partly because the Ming rulers, having never relinquished sovereignty, had a vested interest in the city's prosperity.

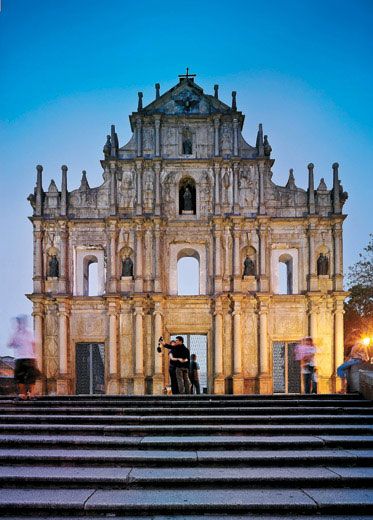

In the 1630s, the Portuguese completed St. Paul's Church, a massive house of worship with an elaborate granite facade surmounted by a carving of a ship with billowing sails watched over by the Virgin Mary. It was the grandest ecclesiastical structure in Asia. But the mercantile empire that funded Catholic evangelism fell under increasing attack from Protestant trading companies from Holland and Great Britain.

In 1639, Portugal was expelled from Japan and lost the source of silver it had used to purchase porcelain, silk and camphor at Cantonese trade fairs. The following year, the dual monarchy that had linked Portugal with Spain for 60 years ended, and with it went Macau's access to the Spanish-American galleon trade. The Dutch captured Malacca in 1641, further isolating Macau. Three years later, Manchu invaders toppled the Ming dynasty.

Macau's glory days were drawing to a close. In 1685, China opened three other ports to competition for foreign trade. By the time St. Paul's accidentally burned in 1835, leaving little beyond the facade, Macau Chinese outnumbered Portuguese six to one and the city's commercial life was dominated by the British East India Company. China's defeat in the Opium War, in 1842, ended the cooperation between the mandarins and the Portuguese. China ceded Hong Kong to Britain and, after nearly three centuries as a guest in Macau, Portugal demanded—and received—ownership of the city.

Still, Hong Kong continued to eclipse Macau, and by the early 20th century, the Portuguese city's golden age was but a memory. "Every night Macau grimly sets out to have fun," French playwright Francis de Croisset observed after visiting the city in 1937. "Restaurants, gambling houses, dance halls, brothels and opium dens are crowded together, higgledy-piggledy.

"Everybody at Macau gambles," de Croisset noted. "The painted flapper who is not a school girl but a prostitute, and who, between two brief spells of dalliance, wagers as much as she can earn in a night; . . . the beggar who has just managed to cadge a coin and now, no longer cringing, stakes it with a lordly air; . . . and finally, the old woman who, with nothing left to wager, to my amazement took out three gold teeth, which, with a gaping smile, she staked and lost."

The Portuguese legacy can still be found in Senate Square, the 400-year-old plaza where black and white cobblestones are arranged to resemble waves hitting the shore. Two of the colonial-era buildings surrounding the square are especially noteworthy: the two-story Loyal Senate, which was the seat of secular authority from 1585 to 1835, and the three-story Holy House of Mercy, an elaborate symbol of Catholic charity with balconies and Ionic columns.

"Prior to the transition [in 1999], I worried about the fate of Portugal's patrimony, but it seems China intends to protect our old buildings," says Macau historian Jorge Cavalheiro, although he still sees "an enormous task" ahead for preservationists. Indeed, the city is growing not by clearing old buildings, but by reclaiming new land from the sea.

Nowhere is that reclamation more evident than in the area called Cotai, which links two islands belonging to Macau, Taipa and Coloane. In Cotai, three of the six gambling concessionaires are spending $16 billion to build seven mega-resorts that will have 20,000 hotel rooms.

"This is the largest development project in Asia," says Matthew Pryor, the senior vice president in charge of more than $13 billion in construction for the Las Vegas Sands Corp. "Three of the world's five largest buildings will stand alongside this road when we're complete in 2011. Dubai has mega-projects like these, but here we had to create the land by moving three million cubic meters of sand from the Pearl River."

It's a bitterly cold day, and rain clouds hide the nearby Lotus Flower Bridge to China. But some 15,000 men are working round-the-clock to complete those 20,000 hotel rooms. They are paid an average of $50 a day. Nobody belongs to a union. "The Sheraton and the Shangri-La are over there," says Pryor, pointing to the skeletons of two reinforced-concrete towers disappearing into the clouds. "That cluster on the opposite side will contain a 14-story Four Seasons, 300 service apartments and a luxury retail mall I call the Jewelry Box."

Carlos Couto arrived in Macau in 1981 as the director of planning and public works and today runs the city's leading architectural firm, CC Atelier de Arquitectura, Lda. Couto has approved plans for nearly $9 billion worth of construction over the next four years. "Portuguese here are working harder than ever before," he says, "because China's ‘one country, two systems' model depends on Macau becoming an international city."

Not everyone is pleased with the city's transformation. When Henrique de Senna Fernandes, an 84-year-old lawyer, looks out the window of his office building on what once was Macau Pria Grande, he sees not the languid quayside and bat-winged fishing junks of his youth but a forest of casinos and banks. "The sea used to be here," he sighs, looking at the sidewalk below. "Now all the fishing junks are gone, and Macau is just a big city where people talk only about money."

Perhaps that is inevitable when so much of it changes hands in such a confined space. U.S. investors are making more than enough in Macau to compensate for declines in Las Vegas. But Stanley Ho, now 86, has bested them. Last year his company, Sociedade de Jogos de Macau, led Macau gambling concessionaires with profits of $230 million. And his daughter Pansy, managing director of his company, Shun Tak Holdings, is a partner in the MGM Grand Macau.

Pansy Ho was born 45 years ago to the second of Ho's four wives. She attended prep school in California and received a degree in marketing and international business management from Santa Clara University. She then moved to Hong Kong, where she started a public relations firm and the local tabloids dubbed her "Party Girl Pansy."

Ho says her Las Vegas colleagues wanted to build a mass-market casino, skeptical that China was rich enough for VIP play. "So four years ago I took MGM's CEO to Shanghai, which was just beginning to show its glamour," Ho says. "I took him to galleries and restaurants and introduced him to billionaires in the making. Now MGM understands what the high-net-worth lifestyle is about."

Foreign investment has changed the character of development, but Macau owes most of its new prosperity to China. The economy of the People's Republic has grown more than 11 percent a year for more than a decade—in Guangdong, the province next to Macau, it's growing 25 percent a year. Shenzhen, across the Pearl River estuary north of Hong Kong, had 230,000 residents in 1980. Now it has 12 million.

Few of today's Chinese visitors are old enough to remember the decade of crushing conformity that came with Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. They are largely the pampered products of one-child families raised under a capitalistic form of communism, and they seem to revel in such touches as the solid gold bars embedded in the lobby floor of Macau Grand Emperor Hotel and the 33-foot-tall, 24-karat gold Tree of Prosperity that rises on the half-hour from beneath an atrium floor at the Wynn casino. Next to the Tree of Prosperity a hallway is lined with deluxe shops. On weekends, lines form outside the Louis Vuitton store, which routinely records monthly sales of $3 million. Watch and jewelry stores regularly achieve daily sales over $250,000. Says a foreign diplomat: "Westerners who come here cross into China to buy fakes, while the Chinese come here to buy the real stuff."

Macau airport is operating at nearly double its capacity, but with 2.2 billion people living within five hours' flying time, it's a good bet that the number will soon double again. Construction on a bridge linking Hong Kong, Macau and Zhuhai in southern China is scheduled to begin soon. Work has begun to expand Macau's northern border gate to accommodate 500,000 visitors a day.

For foreign gambling executives, the biggest challenge would seem to be matching Macau profits back home. "We just have to get more Chinese tourists into the U.S.," jokes Sands Corp. President William Weidner. "This way we can increase our revenues and balance the U.S. trade deficit by winning all the money back at the baccarat tables."

David Devoss has covered Asia for Time and the Los Angeles Times.

One of Justin Guariglia's photographs of Singapore in the September 2007 issue won a Pictures of the Year award.