This Lake Is One of Montana’s Best Kept Secrets

Every summer, writer Boris Fishman returns to Flathead Lake, a pristine spot in northwestern Montana, for rest and reflection

Oh, man, I'm jealous as hell," the guy said, shaking his head, when I told him I'd be spending the Fourth of July weekend at Flathead Lake, in northwestern Montana. We were in Hamilton, at the southern end of the Bitterroot Valley — not exactly ugly country. The snow-crowned brows of the Sapphire Mountains (where you can pan yourself a sapphire in the tailings of the area's numerous mines) peered down at us through the window of the coffee shop where he was pulling my iced mocha. The man himself was heading to the Madison River, near West Yellowstone, a worldwide destination for fly-fishing.

But even in a state as naturally blessed as Montana, which has more than 3,000 lakes, Flathead has distinction. Not only because it runs longer than a marathon — it's the largest freshwater natural lake west of the Mississippi — and ripples with water of gemlike translucence but because often it feels like so few people know about it. Of course, if the lake is little more than a drive-by for the swarm of travelers en route to Glacier National Park and Whitefish, the high-end ski town just to the north, that's just fine with the locals. When I rhapsodize about Flathead, they nod and smile patiently, then say, "Well, don't tell people about it."

I found my way to Flathead a few years ago, shortly after I had published my first novel to a reception that was as unexpectedly enthusiastic as it was draining. In two months, I had performed in front of dozens of rooms, and I desperately wanted silence — and an infusion of energy — for an even longer book tour in the fall, as well as for edits on my second novel. Montana, which I'd been visiting steadily since 2007, has the best silence I've ever found, and I managed to persuade a writer friend to accompany me. (Few other careers offer spontaneous availability and a professional use for silence.) Averill's Flathead Lake Lodge, a much-lauded luxury dude ranch on the northeastern edge of the lake, hits a writer's wallet too hard, and the Islander Inn, eight elegant rooms designed in a coastal aesthetic, was still preparing to open. So we tried Airbnb, where we found a farmhouse on Finley Point, at the lake's southeastern tip, with the water sparkling on one side and the Mission Mountains grandstanding on the other.

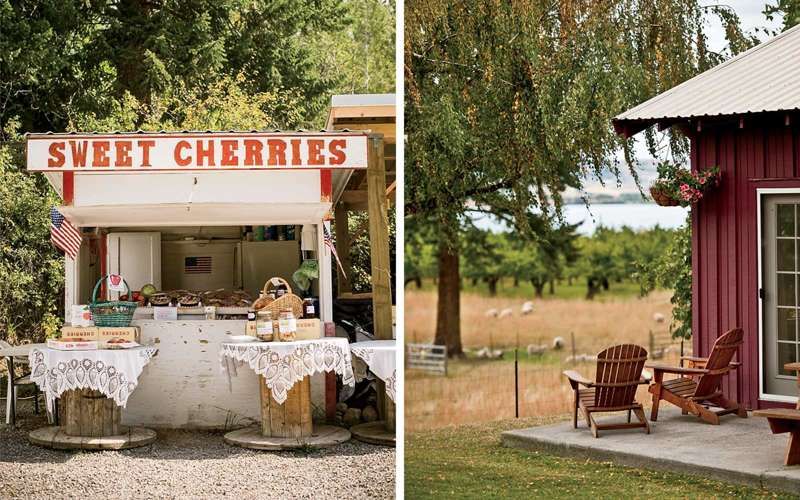

We arrived to find, in the guesthouse fridge, a welcome bowl of cherries, each the size of two thumbs and as dense as a sweetmeat. Flathead is famous for its Lambert cherries, so plump with juice they stain your fingers. Our hosts, Barry and Anita Hansen, grow acres of them, along with a supermarket aisle's worth of vegetables and eight-foot-tall sunflowers, the plot surrounded by the requisite Montana husbandry mix of pigs, chickens, and sheep. (They'd left eggs in our welcome bowl, too, their yolks as orange as tangerines.) Anita, a retired nurse, manages the bursting garden in front of their home — its views even more stupendous than ours — while Barry looks after the farm. After introductions, we scraped the Hansens' cats, Simon and Mia, off the still-warm hood of our car and headed to the lake.

Flathead is a paradox. Its eastern side has attracted snowbirds wealthy enough to keep the heat on even when they are away (to protect the art on the walls), but the small beaches offer little beyond the glory of the lake, to say nothing of fashionable restaurants and shops. In a state sometimes hurting for the dollars that would come with better amenities and more visitors, this is baffling to a New Yorker. "You're looking at it from the human perspective," Barry said to me once. "I'm looking at it from the perspective of the fish."

After my friend and I deposited our towels on a pebbly beach, we quickly learned that, even in late August — when the coldest lakes in the Mountain West lose some of their harshness — Flathead's water is bracing enough to revive a dead man. And no matter how far out I swam, I could see my feet kicking below the sparkling surface. But I could see barely anything else. On that perfect day — 75 degrees, a breeze, zero humidity — my friend and I were almost the only people there.

When the sun began to let up around dinnertime, we drove north to Woods Bay, a town at the lake's northern end that is home to a handful of shops and restaurants, including the Raven, a shambolic, vaguely tropical, mostly open-air tavern with spectacular views of the lake and the most satisfying food in the area — we had fish tacos, braised pork shank, pumpkin roulade, and the kind of cocktails you drink only when you've moved away from a certain kind of urban reality. Clutching our Caribbean Breezes, we were as giddy as the cheesiest tourists, asking again and again to have photos of us taken in the jubilant traveler's well-known delusion that this view of the lake will turn out completely different from that one. It's just the high of witnessing astounding beauty.

By the time we reached home, it was cool enough for sweaters — in the summer, these mountains have a desert-like climate. When it got dark, the sky turned jet-black, and we were treated to a freckling of stars that looked as large as dimes. (No, they were just…visible.) Not a sound from anywhere, save the occasional bleat from one of the Hansens' sheep. I knew I would sleep like a satisfied stone, but I was worried about the next day. I had a passel of second-novel rewrites to deal with, but I'm no good at resisting the kind of sunny enchantment we had encountered. My friends are always amused that this snowbound son of Belarus craves the sun; I'm amused that they don't understand.

But here, too, Flathead seemed intent on serendipity. We woke up to clouds and light rain. (And Simon and Mia scratching at the screen door.) The time it took to dissipate was all I needed at the writing desk. Then we went to the lake. This would become our pattern over the next two weeks: we rose, we wrestled Simon and Mia off our laps as we wrote — "zzzzzzzzzzzzzzz," Simon managed to insert into one of my paragraphs when I stepped away (he wasn't wrong) — and then we headed off to the lake. By early evening, I would be dispatched to the supermarket in the nearby town of Polson or to one of the many family farm stands that line the lake to procure provisions for dinner. (My friend, who is Iranian, cooks only from scratch, and Anita had to forgive quite a few turmeric stains on the guesthouse kitchen counter.) In the evening, we read, talked, walked, and stared at the stars with wine in our hands. We got Internet access from a hot spot lent to us by Anita, but we used it only in the morning. I consulted no newspapers and no social media. The pages I wrote while at Flathead remain, to my mind, some of the strongest in my second novel, which came out last year. Titled Don't Let My Baby Do Rodeo, nearly half of it takes place in Montana.

Before the visit was up, I booked two weeks for the following summer. Tragically, work interfered, so I sent my parents instead. To them — people who'd found the courage to come to America from the Soviet Union — Montana might as well have been Mars, so I flew along to help them settle in. At the Raven, I nearly had to hold their hands (their other hands were on their Caribbean Breezes) as I reassured them all would be well. Then they met Barry and Anita, and I was rapidly forgotten. The Hansens took them out in their boat, had them over for dinner, all but found them housing and jobs. My folks were like children about leaving.

Then last summer, after a volunteer stint at a farm in the Bitterroot Valley, I managed to return, this time with a girlfriend. The splendor around us left her in the same hushed marvel I'd experienced two years before. All the same, I don't think Flathead would mean what it does without Barry and Anita. On this visit, the guesthouse was rented, so they just put us up in their home. We ate dinner together (braised elk and a salad of vegetables from the garden spiked with garlic) and talked past midnight about everything — gun rights, staring, and the Philippines, where their son and his fiancée served in the Peace Corps. Anita got me thinking about her gluten-free, dairy-free diet — with a loophole for logs of grass-fed butter — and I got Barry, a devotee of technical journals, thinking about opening a novel for the first time in years.

One night, to celebrate their son Warren's return from the Philippines, we went out for ice cream, then to a bar in Columbia Falls, 45 minutes away, for some beers amid taxidermy. Later, when Warren wanted to stay behind with his friends, I drove Barry and Anita home. Is there night more lightless than Montana night? But we passed the long ride by playing a ridiculous word game, and our hollering laughter made the surrounding darkness feel only wondrous and tranquil.

You leave a place like Flathead vowing to do things differently at home — waking up with the light, seeing friends more regularly, cooking more — but these plans curdle. Busy urban environments don't tolerate repetition. Perhaps no non-vacation environments do: I haven't been able to subject the hypothesis to adequate testing. I do know that, one day, I would like to bring my kids to Flathead. I would like them to be as versed in silence and serenity as in skyscrapers and subways.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/20/1d206636-d09f-4dd4-afca-bc3928ad036b/istock-186697223.jpg)