Pulitzer-Prize Winning Author John McPhee Recalls Alaska Before Cell Phones, GPS and Most of Its National Parks

McPhee’s trips to Alaska in the 1970s inspired his seminal outdoors narrative “Coming Into the Country” and helped launch his career

:focal(622x723:623x724)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/e7/e6e70038-bd5d-449b-b448-2c5c080fc49e/mcphee_2010c_yolanda_whitman.jpg)

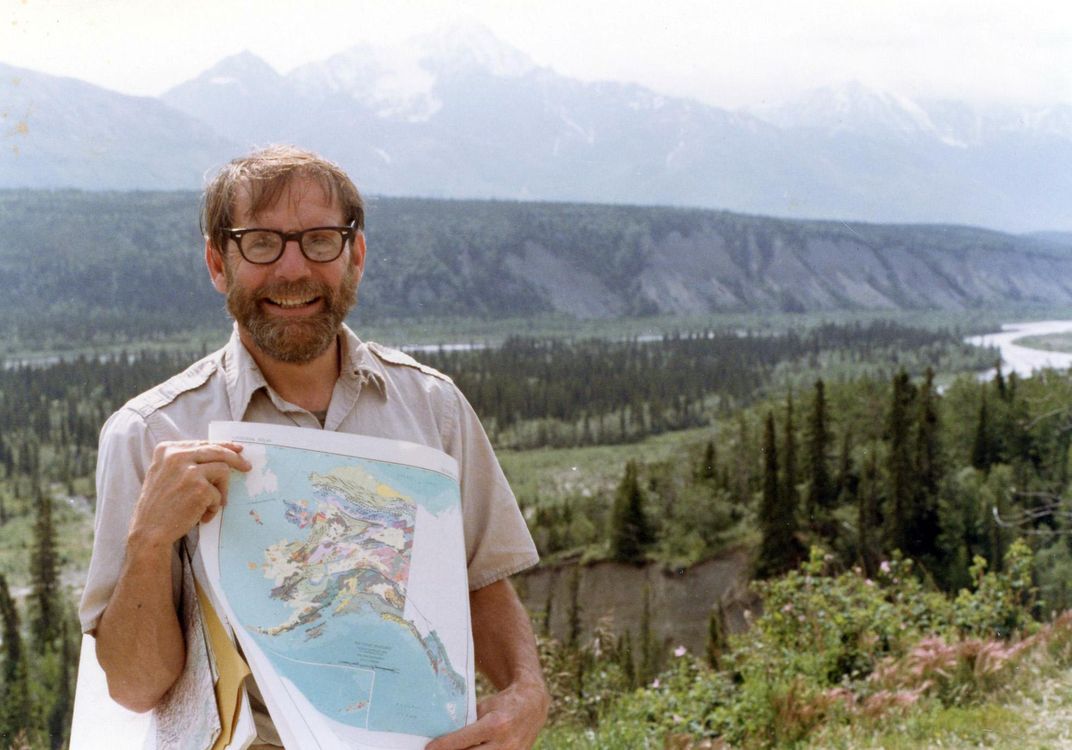

There may be no richer account of Alaska’s great outdoors than John McPhee’s Coming into the Country. His precise language and deft reporting on the place and its people took the longtime New Yorker writer to new heights, earning him a National Book Award nomination. Four decades after the book’s first printing in 1976, McPhee glances back at those early days. From his home in Princeton, New Jersey, he told Smithsonian Journeys quarterly’s associate editor Sasha Ingber about how it all started, from meeting the locals who would become central figures in his book to the sweetness of Alaska snow.

I read that you once took a job at a firm that shipped products, partnered with Pan American Airways, and produced paper from sugarcane—and that you were attracted to “this incredible array of stuff they did.” You also wrote about an “incredible array of stuff,” including geology, truckers, oranges, a basketball player. But what drew you to environmental subjects, such as the upper Yukon region of Alaska in Coming Into the Country?

I went to a summer camp, Keewaydin, in Vermont, from age 6 to 20, ending up as a swimming instructor and canoe-trip leader there. The place specialized in canoes and backpacking, and had an in-camp program that I have described as a “classroom of the woods.” A high percentage of my thematic choices for pieces of writing derive from Keewaydin, and certainly all the environmental subjects, including Alaska.

Beyond your camp years in Vermont and friendship with a park planner, what made Alaska’s Yukon region so intriguing to you?

On my first trip up I accompanied some National Park Service people who were holding hearings in the region of the Upper Yukon. In Circle, Ginny and Ed Gelvin, who lived 33 miles away, told me I should get to know real Alaskans. I said, “So take me home with you.” They did—right after the hearings. The Gelvins would become central figures in Coming Into the Country.

In Eagle I had said to a trapper named Richard O. Cook, “If I come back here someday, will you talk with me?” He said, “Maybe.”

In the 1970s, before cell phones, Google maps, and the establishment of most of Alaska's national parks, what did you expect this remote state to be like? How was it different or similar to what you imagined?

John Kauffmann, on visits back to the East, had told me countless stories about people in Alaska, so they're what I expected. The geography—the wild vastness of Alaska—was something I thought I understood on paper but did not in any tangible sense expect.

Can you share something surprising that you learned about the area or its people while researching? And does it still hold true today?

I remember playing volleyball outdoors with schoolkids in Eagle at 15 below zero and peeling garments until I was playing in a T-shirt. Such a scene was in large part enabled by a lack of wind. The absence of winter wind up there—in the coldest and hottest part of Alaska—was phenomenal. Dry snow in amounts the size of large loaves of bread would build up on each bough of spruce. The snow was so light and dry that you could walk over to a tree, blow on one of those loaves of snow, and—poof—it would vanish. Happy birthday.

You’ve mentioned that your bias is toward the environmental movement. Did the reporting and writing of Coming Into the Country play a role in shaping your environmental awareness?

Not so much shaping as enhancing, I suppose. But my purpose was to present the various sides of the environmental issue and let the reader do the judging.

Have you returned to Alaska since writing the book? If so, how recently and where?

Three times. The hardest thing about what I do is saying farewell to what I’ve done—in this instance as much as any other. When two of my daughters were in college, I took them on a 500-mile canoe trip up there. When Eagle turned 100 as an incorporated community, the town asked me to come to the celebration. That was in 1997. I haven't been back to Alaska since.

Is there one moment that you sometimes look back on from when you were in Alaska?

After three years of long visits, I made a three-mile, midnight walk on the frozen river on my last night there. I still see the green aurora, millions of stars hanging like grapes. The memory makes me both happy and sad.