Inside Cape Town

Tourists are flocking to the city, but a former resident explains how the legacy of apartheid lingers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/capetown_apr08_631.jpg)

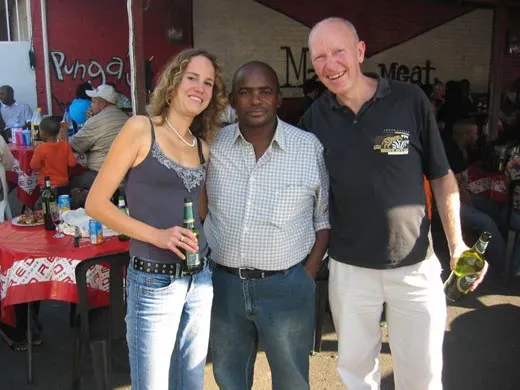

From the deck of a 40-foot sloop plying the chilly waters of Table Bay, Paul Maré gazes back at the illuminated skyline of Cape Town. It is early evening, at the close of a clear day in December. Maré and his crew, racing in the Royal Cape Yacht Club's final regatta before Christmas, hoist the jib and head the sloop out to sea. A fierce southeaster is blowing, typical of this time of year, and Maré's crew members cheer as they tack round the last race buoy and speed back toward shore and a celebratory braai, or barbecue, awaiting them on the club's patio.

Maré, the descendant of French Huguenots who immigrated to South Africa in the late 17th century, is president of the yacht club, one of many white colonial vestiges that still thrive in Cape Town—South Africa's "Mother City." The club, founded in 1904 after the Second Boer War, has drawn an almost exclusively white membership ever since. (Today, however, the club administers the Sail Training Academy, which provides instruction to disadvantaged youth, most of them blacks and coloureds.)

After Nelson Mandela's African National Congress (ANC) won power in South Africa in the democratic elections of 1994 (it has governed since), some of Maré's white friends left the country, fearing that it would suffer the economic decline, corruption and violence that befell other post-independence African nations. Maré's two grown children immigrated to London, but the 69-year-old engineering consultant does not regret remaining in the land of his birth. His life in suburban Newlands, one of the affluent enclaves on the verdant slopes of Table Mountain, is stable and comfortable. His leisure time is centered around his yacht, which he owns with a fellow white South African. "We'll be getting ready for our next crossing soon," says Maré, who has sailed three times across the often stormy south Atlantic.

More than a decade after the end of apartheid, Cape Town, founded in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company's Jan van Riebeeck, is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country. Much of this sprawling metropolis of 3.3 million people at Africa's southern tip has the feel of a European or American playground, a hybrid of Wyoming's Tetons, California's Big Sur and the Provence region of France. White Capetonians enjoy a quality of life that most Europeans would envy—surfing and sailing off some of the world's most beautiful beaches, tasting wine at vineyards established more than 300 years ago by South Africa's first Dutch settlers, and mountain biking on wilderness trails high above the sea. Cape Town is the only major city in South Africa whose mayor is white, and whites still control most of its businesses. Not surprisingly, it's still known as "the most European city in South Africa."

But a closer look reveals a city in the throes of transformation. Downtown Cape Town, where one saw relatively few black faces in the early 1990s (the apartheid government's pass laws excluded nearly all black Africans from the Western Cape province), bustles with African markets. Each day at a central bus depot, combis, or minibuses, deposit immigrants by the hundreds from as far away as Nigeria and Senegal, nearly all of them seeking jobs. The ANC's "black economic empowerment" initiatives have elevated thousands of previously disadvantaged Africans to the middle class and created a new generation of black and mixed-race millionaires and even billionaires. With the racial hierarchy dictated by apartheid outlawed, the city has become a noisy mix of competing constituencies and ethnicities—all jockeying for a share of power. The post-apartheid boom has also seen spiraling crime in black townships and white suburbs, a high rate of HIV infection and a housing shortage that has forced tens of thousands of destitute black immigrants to live in dangerous squatter camps.

Now Cape Town has begun preparing for what will be the city's highest-profile event since the end of white-minority rule in 1994. In 2004, the world soccer federation, FIFA, selected South Africa as the venue for the 2010 World Cup. Preparations include construction of a $300 million, 68,000-seat showcase stadium in the prosperous Green Point neighborhood along the Atlantic Ocean and massive investment in infrastructure. Not surprisingly, the project has generated a controversy tinged with racial overtones. A group of affluent whites, who insist that the stadium will lose money and degrade the environment, has been pitted against black leaders convinced that opponents want to prevent black soccer fans from flooding into their neighborhood. The controversy has abated thanks to a promise by the Western Cape government, so far unfulfilled, to build an urban park next to the stadium. "For Capetonians, the World Cup is more than just a football match," says Shaun Johnson, a former executive of a newspaper group and a top aide to former President Mandela. "It's an opportunity to show ourselves off to the world."

For nearly two years, from August 2005 until April 2007, I experienced Cape Town's often surreal contradictions firsthand. I lived just off a winding country road high in the Steenberg Mountains, bordering Table Mountain National Park and overlooking False Bay, 12 miles south of Cape Town's city center. From my perch, it was easy to forget that I was living in Africa. Directly across the road from my house sprawled the Tokai forest, where I jogged or mountain-biked most mornings through dense groves of pine and eucalyptus planted by Cape Town's English colonial masters nearly a century ago. A half mile from my house, an 18th-century vineyard boasted three gourmet restaurants and a lily-white clientele; it could have been plucked whole from the French countryside.

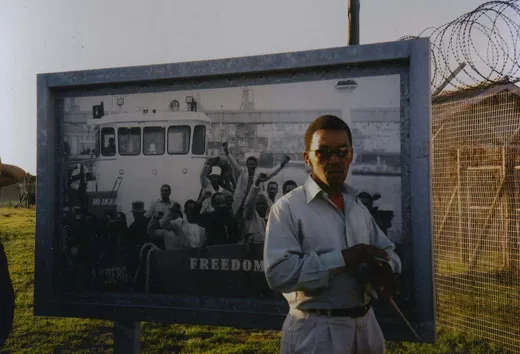

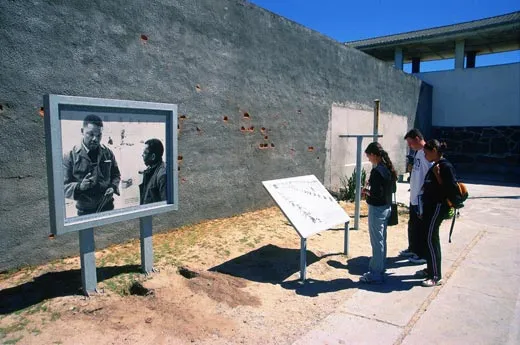

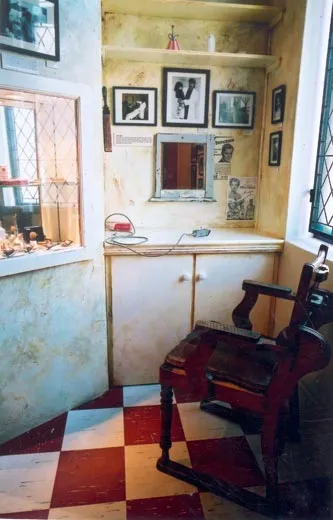

Yet there were regular reminders of the legacy of apartheid. When I drove my son down the mountain to the American International School each morning, I passed a parade of black workers from the townships in the Cape Flats trudging uphill to manicure the gardens and clean the houses of my white neighbors. Next to my local shopping mall, and across the road from a golf course used almost exclusively by whites, stood an even starker reminder of South Africa's recent past: Pollsmoor Prison, where Mandela spent four and a half years after being moved from Robben Island in April 1984.

I also lived within sight of Table Mountain, the sandstone and granite massif that stands as the iconic image of the city. Formed 60 million years ago, when rock burst through the earth's surface during the violent tectonic split of Africa from South America, the 3,563-foot peak once rose as high as 19,500-foot Mount Kilimanjaro. No other place in Cape Town better symbolizes the city's grand scale, embrace of outdoor life and changing face. Table Mountain National Park—the preserve that Cecil Rhodes, prime minister of the Cape Colony in the late 19th century, carved out of private farms on the slopes of the mountain—has grown into a 60,000-acre contiguous wilderness, extending from the heart of the city to the southern tip of the Cape Peninsula; it includes dozens of miles of coastline. The park is a place of astonishing biodiversity; 8,500 varieties of bush-like flora, or fynbos—all unique to the Western Cape—cover the area, along with wildlife as varied as mountain goats, tortoises, springboks and baboons.

One December day I drive up to the park's rustic headquarters to meet Paddy Gordon, 44, area manager of the park section that lies within metropolitan Cape Town. Gordon exemplifies the changes that have taken place in the country over the past decade or so: a mixed-race science graduate of the once-segregated University of the Western Cape, he became, in 1989, the first nonwhite appointed to a managerial job in the entire national park system. Within 12 years he had worked his way up to the top job. "Before I came along we were only laborers," he says.

We drive high above the city along Kloof Road—a lively strip of nightclubs, French bistros and pan-Asian restaurants. After parking the car in a tourist lot at the base of the mountain, we begin climbing a rocky trail that hundreds of thousands of hikers follow each year to Table Mountain's summit. In a fierce summer wind (typical of this season, when frigid antarctic currents collide with southern Africa's warming landmass), Gordon points out fields of wild olives and asparagus, fynbos and yellow fire lilies, which burst into flower after wildfires that can erupt there. "We've got the greatest diversity in such a small area of anywhere in the world," he says, adding that development and tourism have made the challenges of conservation more difficult. In January 2006, at the height of Cape Town's summer dry season, a hiker dropped a lit cigarette in a parking lot at the base of this trail. Within minutes, fire spread across the mountain, asphyxiating another climber who had become disoriented in the smoke. The fire burned for 11 days, destroying multimillion-dollar houses and requiring the efforts of hundreds of firefighters and helicopters ferrying loads of seawater to extinguish. "It burned everything," Gordon tells me. "But the fynbos is coming up pretty well. This stuff has an amazing ability to regenerate itself."

Gordon points out a clear trailside stream created by mist condensation at the top of the plateau. "It's one of the only water sources on the mountain's western face," he says. The stream, Platte Klipp, was the primary reason that the 17th-century Dutch seaman Jan van Riebeeck built a supply station for the Dutch East India Company at the base of Table Mountain. The station grew into a thriving outpost, Kaapstadt; it became the starting point for the Voortrekkers, Dutch immigrants who crossed desert and veld by ox wagon to establish the Afrikaner presence across southern Africa.

The Mother City has steered the nation's destiny ever since. In 1795, the British seized Cape Town, maintaining their hold over the entire colony for more than 100 years. Even today, English- and Afrikaans-speaking whites gravitate toward opposite corners of the city. English speakers prefer the southern suburbs around Table Mountain and beachfront communities south of the city center. Afrikaners tend to live in northern suburbs a few miles inland from the Atlantic coast. The British introduced the first racist laws in the country, but it was the Afrikaner Daniel François Malan—born just outside Cape Town—who became the main proponent of white-racist philosophy. In 1948, Malan's National Party swept to victory; he became prime minister and codified his racist views into the legal system known as apartheid.

The Group Areas Act of 1950 banished all black Africans from Western Cape province, except those living in three black townships. Cape coloureds (predominantly mixed-race, Afrikaans-speaking descendants of Dutch settlers, their slaves and local indigenous inhabitants) became the main source of cheap labor; they remained second-class citizens who could be evicted from their homes by government decree and arrested if they so much as set foot on Cape Town's segregated beaches. From 1968 to 1982, the apartheid regime forcibly removed 60,000 coloureds from a neighborhood near the city center to the Cape Flats, five miles from downtown Cape Town, then bulldozed their houses to make room for a proposed whites-only development. (Protests stopped construction; even today, the neighborhood, District Six, remains largely a wasteland.)

During the height of anti-apartheid protests in the 1970s and 1980s, Cape Town, geographically isolated and insulated from racial strife by the near absence of a black population, remained quiet in comparison with Johannesburg's seething townships. Then, during the dying days of apartheid, blacks began to pour into Cape Town—as many as 50,000 a year over the past decade. In the 1994 election campaign, the white-dominated National Party exploited coloureds' fear that a black-led government would give their jobs to blacks; most chose the National Party over the ANC. While many blacks resent mixed-race Capetonians for their failure to embrace the ANC, many coloureds still fear black competition for government grants and jobs. "The divide between blacks and coloureds is the real racial fault line in Cape Town," I was told by Henry Jeffreys, a Johannesburg resident who moved to Cape Town last year to become the first nonwhite editor of the newspaper Die Burger. (A former editor was the architect of apartheid, D. F. Malan.)

But the gap is closing. The Western Cape province, of which Cape Town is the heart, boasts one of the fastest-growing economies in South Africa. An infusion of foreign and local investment has transformed the once moribund city center into what civic leader Shaun Johnson calls a "forest of cranes." In late 2006, a Dubai consortium paid more than $1 billion for the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront, a complex of hotels, restaurants and shops—and the terminal for ferries that transport tourists across Table Bay to Robben Island. The price of real estate has skyrocketed, even in once-rundown seaside neighborhoods such as Mouille Point, and the bubble shows no signs of bursting.

The new economic activity is enriching South Africans who couldn't dream of sharing in the wealth not that long ago. One bright morning, I drive south along the slopes of Table Mountain to Constantia Valley, a lush expanse of villas and vineyards; its leafy byways epitomize the privileged lives of Cape Town's white elite—the horsey "mink and manure set." I have come to meet Ragavan Moonsamy, 43, or "Ragi," as he prefers to be called, one of South Africa's newest multimillionaires.

Here, bougainvillea-shrouded mansions lie hidden behind high walls; horse trails wind up forested hills cloaked in chestnut, birch, pine and eucalyptus. Armed "rapid response" security teams patrol the quiet lanes. I drive through the electric gates of a three-acre estate, passing landscaped gardens before I pull up in front of a neocolonial mansion, parking beside a Bentley, two Porsches and a Lamborghini Spyder. Moonsamy, wearing jeans and a T-shirt, is waiting for me at the door.

As recently as 15 years ago, the only way that Moonsamy would have gained entrance to this neighborhood would have been as a gardener or laborer. He grew up with eight siblings in a two-room house in Athlone, a dreary township in the Cape Flats. His great-grandparents had come to the South African port of Durban from southern India to work the sugar-cane fields as indentured servants in the late 19th century. Moonsamy's parents moved illegally from Durban to Cape Town in the 1940s. He says he and his siblings "saw Table Mountain every day, but we were indoctrinated by apartheid to believe we do not belong there. From the time I was a young teenager, I knew I wanted to get out."

After graduating from a segregated high school, Moonsamy dabbled in anti-apartheid activism. In 1995, as the ANC government began seeking ways of propelling "previously disadvantaged" people into the mainstream economy, Moonsamy started his own finance company, UniPalm Investments. He organized thousands of black and mixed-race investors to buy shares in large companies such as a subsidiary of Telkom, South Africa's state-owned phone monopoly, and bought significant stakes in them himself. Over ten years, Moonsamy has put together billions of dollars in deals, made tens of millions for himself and, in 1996, purchased this property in the most exclusive corner of Upper Constantia, one of the first nonwhites to do so. He says he's just getting started. "Ninety-five percent of this economy is still white-owned, and changing the ownership will take a long time," he told me. Speaking figuratively, he adds that the city is the place to seize opportunity: "If you want to catch a marlin, you've got to come to Cape Town."

Not everybody catches marlin. Zongeswa Bauli, 39, is a loyal member of the ANC who wears Nelson Mandela T-shirts and has voted for the party in every election since 1994. One afternoon I travel with her to her home at the Kanana squatter camp, an illegal settlement inside the black township of Guguletu, near Cape Town's airport. In 1991, the dying days of apartheid, Bauli arrived here from destitute Ciskei—one of the so-called "independent black homelands" set up by the apartheid regime in the 1970s—in what is now Eastern Cape province. For nine years, she camped in her grandmother's backyard and worked as a domestic servant for white families. In 2000, she purchased a plot for a few hundred dollars in Kanana, now home to 6,000 black migrants—and growing by 10 percent annually.

Bauli leads me through sandy alleys, past shacks constructed of crudely nailed wood planks. Mosquitoes swarm over pools of stagnant water. In the courtyard of a long-abandoned student hostel now taken over by squatters, rats scurry around heaps of rotting garbage; residents tell me that someone dumped a body here a month ago, and it lay undiscovered for several days. While free anti-retroviral drugs have been introduced in Cape Town, the HIV rate remains high, and the unemployment rate is more than 50 percent; every male we meet, it seems, is jobless, and though it's only 5 p.m., most appear drunk. As we near her dwelling, Bauli points out a broken outdoor water pump, vandalized the week before. At last we arrive at her tiny wooden shack, divided into three cubicles, where she lives with her 7-year-old daughter, Sisipho, her sister and her sister's three children. (After years of agitation by squatters, the municipality agreed in 2001 to provide electricity to the camp. Bauli has it, but thousands of more recent arrivals do not.) After dark, she huddles with her family indoors, the flimsy door locked, terrified of the gangsters, called tsotsis, who control the camp at night. "It's too dangerous out there," she says.

Bauli dreams of escaping Kanana. The ANC has promised to provide new housing for all of Cape Town's squatters before the World Cup begins—the "No Shacks 2010" pledge—but Bauli has heard such talk before. "Nobody cares about Guguletu," she says with a shrug. Bauli's hopes rest on her daughter who is in second grade in a public primary school in the affluent, largely white neighborhood of Kenilworth—an unattainable aspiration in the apartheid era. "Maybe by 2020, Sisipho will be able to buy me a house," she says wryly.

Helen Zille, Cape Town's mayor, largely blames the ANC for the housing crisis: the $50 million that Cape Town receives annually from the national government, she says, is barely enough to build houses for 7,000 families. "The waiting list is growing by 20,000 [families] a year," she told me.

Zille's own story reflects the city's complex racial dynamics. In the last local election, her Democratic Alliance (DA), a white-dominated opposition party, formed a coalition with half a dozen smaller parties to defeat the incumbent ANC. (Many coloured voters turned against the ANC once again and helped give the DA its victory.) It was one of the first times in South Africa since the end of apartheid that the ANC had been turned out of office; the election results created a backlash that still resonates.

Zille, 57, is one of only a few white politicians in the country who speak Xhosa, the language of South Africa's second-largest tribe, and lives in a racially integrated neighborhood. She has an impressive record as an activist, having been arrested during the apartheid years for her work as a teacher in Crossroads, a black squatter camp. Despite her credentials, the ANC-controlled Western Cape provincial government launched an effort last fall to unseat and replace her with a "mayoral committee" heavily represented by ANC members. Their complaint: the city was not "African" enough and had to be brought in line with the rest of the country. After protests from Zille supporters and criticism from even some ANC allies, the leadership backed down.

The wounds are still raw. Zille bristled when I asked her about being heckled at a rally she attended with South African President Thabo Mbeki. She said the heckling was "orchestrated" by her enemies within the ANC. "This election marked the first time that the party of liberation has lost anywhere in South Africa," she said as we sat in her spacious sixth-floor office in the Civic Center, a high-rise overlooking Cape Town's harbor. "The ANC didn't like that." As for the claim that Cape Town wasn't African enough, she scoffed. "Rubbish! Are they saying that only Xhosa people can be considered African? The tragedy is that the ANC has fostered the misimpression that only black people can take care of blacks."

The Koeberg Nuclear Power Station, Africa's only nuclear power plant, was inaugurated in 1984 by the apartheid regime and is the major source of electricity for the Western Cape's 4.5 million population. I've come to meet Carin De Villiers, a senior manager for Eskom, South Africa's power monopoly. De Villiers was an eyewitness to one of the worst crises in South Africa's recent history, which unfolded at Koeberg for two frantic weeks in early 2006. It may well have contributed to the defeat of the ANC in the last election.

On February 19, 2006, an overload on a high-voltage transmission line automatically tripped the nuclear reactor's single working unit (the other had earlier sustained massive damage after a worker dropped a three-inch bolt into a water pump). With the entire reactor suddenly out of commission, the whole Western Cape became dependent on a coal-fueled plant located more than 1,000 miles away. As engineers tried desperately to get one of the two 900-megawatt units back on line, Eskom ordered rolling blackouts that paralyzed Cape Town and the region, as far as Namibia, for two weeks. "It was a nightmare," De Villiers told me. Businesses shut down, traffic lights stopped working, gas pumps and ATMs went dead. Police stations, medical clinics and government offices had to operate by candlelight. After the city's pumps shut down, raw sewage poured into rivers and wetlands, killing thousands of fish and threatening the Cape Peninsula's rich bird life. Tourists were stranded in cable cars on Table Mountain; burglars took advantage of disabled alarms to wreak havoc in affluent neighborhoods. By the time Eskom restored power on March 3, the blackouts had cost the economy hundreds of millions of dollars.

For De Villiers and the rest of Cape Town's population, the power failures provided an unsettling look at the fragility that lies just beneath the city's prosperous surface. It drew attention to the fact that Eskom has failed to expand power capacity to keep up with the province's 6 percent annual growth and opened the ANC to charges of poor planning and bad management. Now Eskom is scrambling to build new plants, including another nuclear reactor, as the city prepares for the World Cup. The power collapse also laid bare racial grievances: many whites, and some nonwhites as well, saw the breakdown as evidence that the official policy of black economic empowerment had brought unqualified people into key positions of responsibility. "Given the mismanagement of this economy à la Eskom, I am beginning to prefer my oppressors to be white," one reader wrote to Business Day, a South African newspaper.

Paul Maré considers such rough patches a natural, if frustrating, part of the transition to real democracy. Standing on the deck of the Royal Cape Yacht Club at twilight, with a glass of South African chardonnay in one hand and a boerewors (grilled sausage) in the other, Maré takes in the glittering lights of downtown Cape Town and the scene of prosperous white South Africa that surrounds him. Maré's partner, Lindsay Birch, 67, grumbles that in the post-apartheid era, "it's hard for us to get sponsorship for our regattas. Sailing isn't a black sport." Maré, however, is putting his bets on Cape Town's future—and his place in it. "I'm an African," Maré says. "I've got 350 years' worth of history behind me."

Formerly Newsweek's bureau chief in Cape Town, writer Joshua Hammer is a freelancer who is based in Berlin.

Photographer Per-Anders Pettersson resides in Cape Town.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)