Iceland Be Dammed

In the island nation, a dispute over harnessing rivers for hydroelectric power is generating floods of controversy

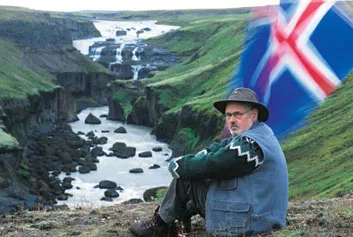

Beginning with this footstep, we would find ourselves underwater,” says wildlife biologist Skarphedinn Thorisson as he starts walking down the slope of a wide, bowl-shaped valley. It lies just beyond the northeastern- most reaches of Iceland’s vast, volcano-studded Vatnajokull glacier. He crosses an invisible line into imperiled terrain: a proposed hydroelectric dam project would inundate 22 square miles of rugged landscape, a place scored by a glacial ice-melt river, the Jokulsa a Bru, and ice-melt streams. As Thorisson heads deeper down the steep incline layered in black, gravel-strewn soil, he adds: “What is at risk here is Western Europe’s largest highland wilderness.”

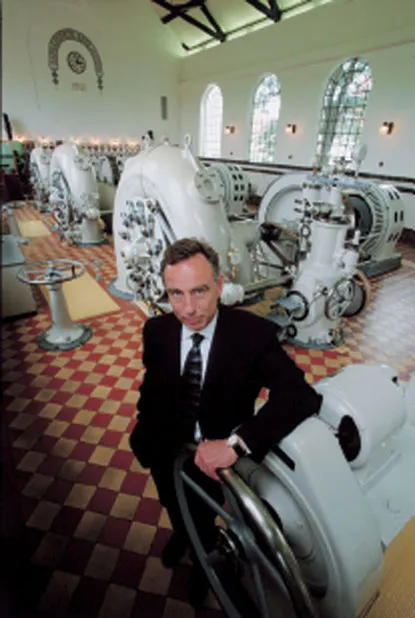

The plan is as complex as it is controversial. The river, dammed and diverted to flow into a 25-mile-long tunnel, would then funnel into a second river. The combined wa- terways, feeding into a new underground power plant, would generate up to 750 megawatts of electricity to supply a proposed aluminum smelter in Iceland’s eastern fjord country.Pro-developmentfactionspointoutthat600 workers could be employed at such a facility. Iceland’s prime minister, David Oddson, insists the project “will not spoil the landscape.”

Even more is at stake than the construction of a single dam, the Karahnjukar (named after the conical peak rising just east of the dam site). If it gets built, plans call for a se- ries of perhaps as many as eight smaller dams. Inevitably, a network of roads would follow. At some point decades hence, critics maintain, a wilderness of about 400 square miles would cease to exist.

Iceland’s 283,000 inhabitants are divided on the question of whether to dam the rivers. While 47 percent of Ice- landers support the project, 30 percent oppose it. (Another 23 percent say they are undecided.)

In this upland microclimate, outside the icy recesses of the glacier, “the weather is milder, the snowfall lighter,” says Thorisson. As a result, alpine vegetation, important sustenance for both reindeer and flocks of pink-footed geese, flourishes on the threatened hillsides.

Advocates of the project contend there is more than enough untrammeled territory to go around. As for the reindeer, they assert, herds are thriving. In addition, a state- of-the-art smelter would incorporate pollution-control technology. “The new factories are nothing like the manufacturing facilities that existed in the past,” says one official. Critics counter that tourism is more vital to the national economy than industrialization. “Travelers come to Iceland be- cause they have an image of a country that is relatively un- touched,” says Arni Finnsson of the Iceland Nature Conserva- tion Association. “These pristine areas will only become more valuable as time goes by.” Ecotourism is increasing exponen- tially. In 1995, for instance, 2,200 visitors came to Iceland for whale-watching cruises; last year, that number had soared to more than 60,000.

Both sides agree that if the dam is built, water levels at the new reservoir would fluctuate seasonally. Estimates range from 170 to nearly 250 feet. As a result, environmentalists claim, most submerged vegetation would die off, leaving a muddy morass when the waters recede. The sunbaked mud would turn to dust, to be carried on the winds and coating alpine uplands for miles around. Critics say further that damage could extend far beyond the highlands. The increased volume of water, from the combined and diverted rivers, would eventually flow toward the sea, mostlikelyraisingwater levelsinestuarineareasalongthe coast and causing potentially serious erosion.

On land overlooking that coastal area, farmer Orn Thorleifs- son established his hayfields and a youth hostel 20 years ago. He worries that his low-lying fields are at risk. “The project could destroy agriculture in a place where farming has been carried on for a thousand years.”

The project’s outcome remains unresolved. Last summer, Iceland’s Planning Agency ruled that the plan’s benefits did not outweigh the potential for “irreversible” harm to Iceland’s wilderness. Then, in December, the environmental minister re- versed that decision and gave the project a green light. A citizen coalition is appealing that decree, and a final judgment may be a matter of months—or it could take years.

Should the activists prevail, they already have a name for the 8,000-square-mile preserve they hope to create. Says environ- mentalist Arni Finnsson: “We would call it the National Park of Fire and Ice.”