As much of the world continues to shelter in place, those states and countries slowly easing restrictions are heading out into a world adorned with new art. Graffiti artists, street artists and muralists have been taking over public spaces during the pandemic, using their art forms to express beauty, support and dissent.

One of the newest pieces is in Milwaukee, a colorful, geometric mural by local artist Mauricio Ramirez that depicts a front-line medical worker in prayer. In Dublin, a neon-hued psychedelic coronavirus graces a wall, painted by SUBSET, an artist collective that focuses on social issues. In Berlin, there's a mural of Gollum from Lord of the Rings worshipping a roll of toilet paper. Even more coronavirus-inspired art can be found on walls in Russia, Italy, Spain, India, England, Sudan, Poland, Greece, Syria, Indonesia and elsewhere.

Smithsonian magazine spoke to Rafael Schacter—anthropologist and curator focusing on public and global art, senior teaching fellow in material culture at the University College London and author of The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti—about the current coronavirus art movement. Schacter addressed why the art is so important to our collective experience during this pandemic, and what it means for the art world in the future.

Why is this type of creativity needed right now, during this time of crisis?

The very concept of 'the public,' both in terms of people and in terms of space, is really being stretched right now. We’re also in a time where scrutiny of public policy, discourse and debate is hugely important. One of the spaces where that debate can emerge, especially among those who are marginalized or less able to speak within the media, is the street. A lot of issues of public space that were issues before the crisis—like increasing privatization, surveillance, increasing marginalization, corporatization, housing—are coming forward with the crisis. And these are issues which are often discussed through the medium of the street.

The crisis is not a leveling one. This whole idea of the crisis targets everyone the same, it really doesn’t. All our struggles are being exacerbated by the virus. Discourse emerges out of our ability to congregate, to protest, to come together. At a time where our ability to be in public is lessened, when the public space is being evaporated and displaced, it’s even more important that we’re able to have that space for debate. Yet we’re in a situation where we can’t be in that space. When one’s voice needs to be heard in public and public becomes a danger itself, it’s even more important that scrutiny and dissent is able to be articulated. Graffiti is a space where dissent can be articulated and discourse can be pronounced. And even though it’s in many ways more difficult to produce because you can’t be in the public space, the focus on it becomes ever sharper because everything else is so empty around it.

How is coronavirus street art and graffiti pushing forward the world conversation about art and the virus itself?

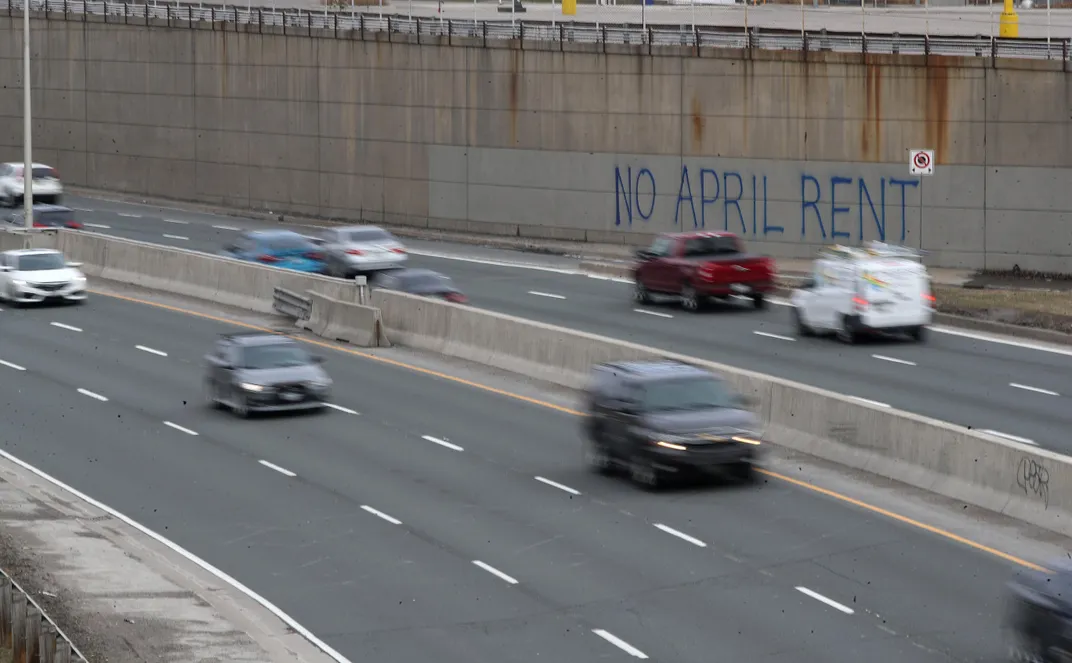

We’re having to use the digital public sphere for sharing and viewing art for the most part. So on that side of things, perhaps this will be the moment where that shift really does take place. There will actually be more thought taken about the way we view art online. On a more a local scale, there’s a lot of graffiti popping up about issues such as rent strikes and issues related to basic needs of survival. Plus, a lot of graffiti now is about 5G or conspiracy theories. Of course, that leads us to think about the people who fall into conspiracy theory thinking. When you’re most powerless, it’s the safest thing to have a conspiracy theory to make us feel better about understanding things. I’m noticing a lot of that kind of graffiti emerging.

Have you seen any parallels between graffiti and street art during the coronavirus and during other pivotal moments of history?

It’s such an odd situation we’re in now, where just being in a public space is more difficult than ever. Not only does that make it more difficult to produce graffiti because there’s a more surveilled view of the public space, meaning you can’t hide in plain sight, but also our ability to see it is lessened because we’re all at home. The public is now in private so in many ways it’s hard to parallel this with anything in the more recent frame. I think the rent strike graffiti, which is what I’ve seen most prominently, is something we’ve seen throughout politics of the last ten years. I saw some really interesting graffiti from Hong Kong recently. It said, 'There can be no return to normal, because normal was the problem in the first place.' That’s very powerful. A lot of the most powerful work I’ve seen is coming out of that occupy, anti-austerity protest aesthetic. This is political graffiti. This is graffiti that is part of the debate around contemporary politics, but from a voice which is often unable to enter into more mainstream political debate.

What does art mean to the human experience?

Humans have been producing art before they were even human. We’ve found wonderful cave paintings, Neanderthal decorative art. There’s an innate need to relate our experience, and I think a lot of art is also about relating with each other. It’s about trying to transmit one’s experience to others or create experiences together in a more classical ritual. The way we understand art now, in western history, is a tiny dot in the history of humankind’s relationship with producing art. But an integral part of human existence is producing art. It will always be a necessity. There’s this idea that it’s only produced when you have all your other basic needs taken care of, but art is a basic need.

How do you feel that this current movement will be reflected in art in the future?

The one thing I hope is that we rethink digital public art [public art that is shared online through social media or other internet capabilities]. Rather than just being an addition to the existing practice, we can really try and start thinking about a way to use the digital public sphere to really engage the people that otherwise wouldn’t be engaged by this kind of practice. There’s a real possibility of creating new audiences.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/ea/1aeaf0e2-4a88-4447-833d-a5e1404b667f/coronavirus_street_art-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/7a/b57abf4d-1812-454c-ba8d-7534c1872de5/coronavirus_street_art-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)