Finders, Keepers: Five of the Best Places to Go Gem Hunting in the U.S.

From diamonds to emeralds, the United States is full of buried bling

:focal(1380x238:1381x239)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/ea/d0ea1dd7-4a0c-449d-905b-b563fb3b5c26/42-17493873.jpg)

Do you dream of the good life? For a lucky few, treasure may lie hidden beneath your feet. Across the United States there are dozens of public mining and digging sites packed with everything from diamonds and emeralds to jade and sunstone. The secret is knowing where to sink your shovel.

Often called “rockhounding,” the search for gems and minerals has been popular for decades. One of the earliest accounts of mining in what is now the United States comes from the Pueblo, a Southwestern tribe that began mining for turquoise some 2,600 years ago. As early Anglo settlers spread the word about the wealth of buried treasures beneath the land, immigrants flocked to the colonies to stake their claim.

The hunt for buried treasure is so interwoven into U.S. history that even today every state in the union has either a state gem or mineral—or both. (Generally speaking, minerals are inorganic objects containing a specific chemical makeup and molecular structure. Gems are precious or semiprecious minerals that can be cut and polished into colorful stones. Gold is neither a gem nor a mineral—it’s a chemical element.)

Today nearly every state has at least one fee-based mine or dig site that’s open to the public with a "finders, keepers" policy that allows visitors to pocket their finds. (Some places will even cut, polish and set found minerals into jewelry for a fee.) In North Carolina, for example, 50,000 treasure hunters try their luck at Emerald Hollow Mine each year. It’s the only site in the country where the public can search for emeralds and North Carolina Hiddenite, a lime-green gem (from the mineral spodumene) discovered in the area in 1879. The rare specimen can prove elusive, but it’s all about the thrill of the hunt.

“Hiddenite is small and can be difficult to find,” Jason Miller, co-owner of Emerald Hollow Mine, tells Smithsonian.com. “Oftentimes people mistake it for green bottle glass, because a shard of glass looks very similar.” North Carolina isn’t the only state that can call dibs on a unique gem or mineral.

Most gem hunters visit sites like Emerald Hollow Mine for the fun of it, but for others, like Karla Proud, it’s a profession. Proud has been hunting gems since her grandfather, a miner during the Great Depression, took her on a digging expedition in the 1950s. She specializes in finding Oregon Sunstone, the state gem (from the mineral labradorite) characterized by its glittery, orange-red hue and formed as the result of lava flow from volcanic eruptions that occurred millions of years ago.

Proud sells the cut and polished gems as jewelry, but sometimes her work takes her beyond her home state. One of her greatest hauls was in 1972, when she discovered massive quantities of tourmaline in a mine she and her ex-husband leased in Pala, California, 60 miles north of San Diego. One of her finds, called the “Candelabra” tourmaline (from the mineral elbaite), is now on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Another, also a tourmaline, wound up on a ten-cent postage stamp in 1974.

“One of the foremen called me on the phone late at night, and his voice was shaking,” Proud tells Smithsonian.com. “At first I thought someone had been hurt, but he was just so excited. [My ex-husband and I] grabbed a case of beer—you didn’t have plastic water bottles back then—and drove to the cave. It was so dark inside that we were pouring beer on the specimens to see what their colorations were.”

Although Proud hasn’t struck similar paydirt in a while, she’s still an avid collector and is well known within the greater gem and mineral community. She joins pros and amateurs alike most winters at the Tucson Gem & Mineral Show in Arizona. The largest show of its kind in the world, annual event features panel discussions, lectures, booths and gems galore.

Though many attendees go for the jewelry, Gloria Quigg, publicity and show chair for TGMS, tells Smithsonian.com that part of the draw is the chance to mingle with other collectors who see the show as a chance to show off their finds. Not every gem on display looks impressive, but don’t discount seemingly simple rocks and stones. Quigg says that often, rockhunters choose to keep their finds intact rather than cut and polish them. Either way, the show offers plenty of chances to see specimens without getting dirty.

Jeffrey Post, who curates the Smithsonian Institution's National Gem and Mineral Collection, was at the Tucson show last February, where he rubbed shoulders with amateur and pro rockhounds and scored some rare gems. Among his finds was a tourmaline crystal cluster from Brazil called "the cranberry crown": a gem studded with delicate, nine-inch-long crystals that jut away from its base in all directions. He purchased a domestic, gem, too—an emerald from North Carolina that he tells Smithsonian.com "was unlike anything we've ever seen."

Post, who has been collecting and hunting for gems since he was a kid, says that there's a growing trend of treating and presenting gems as fine art. That rising cachet means rising prices, too. But he says that people can enjoy gem hunting no matter what the budget. Last year, he spent time at Rock Creek, Montana at a working sapphire mine that's also open to the public. He brought along a group of donors and friends, all of whom soon became enamored by the simple task of sifting through a pile of rocks for hidden treasure. "There's a legitimate sense of being able to find something that could be valuable," he says. "I couldn't drag them away."

Intrigued by the idea of finding a bit of bling in plain sight? Here are five public dig sites worth rolling up your sleeves for:

Emerald Hollow Mine (Hiddenite, North Carolina)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c6/bf/c6bf2b81-33a8-4b7e-b633-d73bdf60f556/20150922_160121.jpg)

Tucked in the foothills of the Brushy Mountains in western North Carolina, Emerald Hollow Mine is the only emerald mine in the United States that’s open to the public. It’s also the only spot in the country where North Carolina Hiddenite, a rare gemstone discovered by geologist William Earl Hidden in 1879, can be found. The stone is known for its high chromium content, which gives it a lime-green hue, and forms in the hydrothermal veins of rocks. Visitors to the mine are equipped with a shovel, a pickaxe and a bucket and can hunt for emeralds, hiddenite, quartz and 60 other gems and minerals at its seven-acre dig site. There’s also a full-service lapidary on site that can transform rough stones into glittering mementos.

Crater of Diamonds State Park (Murfreesboro, Arkansas)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/ea/d0ea1dd7-4a0c-449d-905b-b563fb3b5c26/42-17493873.jpg)

A visit to most state parks includes a hike or a bit of fly fishing. But Crater of Diamonds State Park brings something different to the table: some serious bling. Located about 115 miles southwest of Little Rock on the site of a volcanic crater, the park is a hotbed of buried diamonds crystallized from carbon, which formed in the earth's mantle billions of years ago and were thrust to the surface by the crater's explosion. In June 2015, one lucky visitor unearthed an 8.52-carat diamond—the fifth largest specimen found at the park since it opened in 1972—and the site regularly updates its list of record finds. Thanks to the mineral’s brilliant luster, a would-be diamond hunter’s best tool is often their own eyes, and it's not uncommon to find diamonds glistening in the soil.

Jade Cove Trail (Big Sur, California)

Don’t let the breathtaking ocean views that surround this central California trail distract you from something just as spectacular: the ground. The one-and-a-half mile Jade Cove Trail is a popular spot for jade hunters searching for the greenish-hued gemstone, which forms due to subduction or when oceanic and continental plates collide. Because the trail is part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has released strict guidelines for jade hunting, but as long as specimens are in plain sight, rockhounds are welcome to pocket them. The region is also home to the annual Big Sur Jade Festival. This year, due to the Soberanes forest fire, the event has been rescheduled for the spring.

Morefield Mine (Amelia County, Virginia)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/2b/a82b1ea6-7142-49d6-b89d-cae306f7976c/8656953067_8560a827e2_o.jpg)

During World War II, Morefield Mine, located just outside of Richmond, Virginia, was used by military suppliers in search of strategic minerals like mica, beryl and tantalum for use in tanks and artillery. Today, it’s privately owned and is a popular site to hunt for amazonite, a greenish gem named after the Amazon River, and 80 other gems and minerals. Located 300 feet under ground and stretching 2,000 feet in length, the mine is always growing and changing. The area formed more than 250 million years ago when magma pushed from the center of the earth to the surface and cooled, leaving behind massive deposits of minerals. The mine owners periodically use explosives to blast the cave and open up new areas for visitors to explore. Equipped with five-gallon buckets (hammers and pickaxes aren’t allowed), diggers can bring home whatever they can fit into a single bucket.

Graves Mountain (Lincolnton, Georgia)

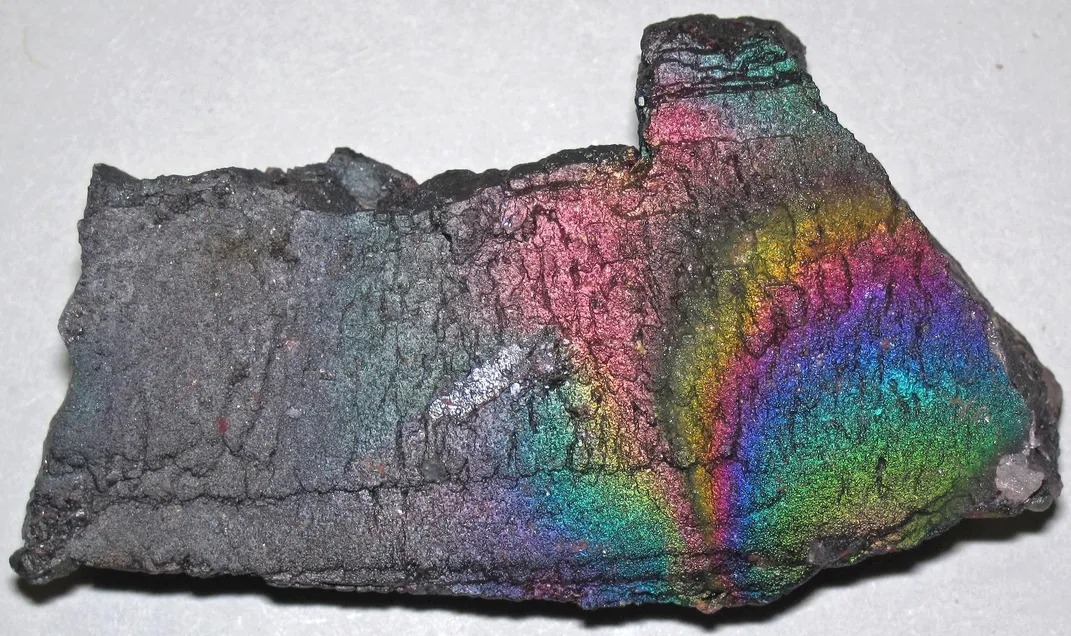

Several times each year, the caretakers of Graves Mountain, located about 130 miles east of Atlanta, invite visitors to dig for buried treasure at this site, which formed millions of years ago when sedimentary rocks metamorphosed. At one time, Tiffany & Co. mined the site for rutile, a crystal-like mineral it used to polish its collection of diamonds. Large traces of the mineral can still be found there today. The mountain’s next dig and rock swap will be held October 7 through October 9—participants can bring their own shovels and hand tools to search for quartz, iridescent hematite, bluish lazulite and other specimens.