Hawaii’s Last Outlaw Hippies

After half a century, the counterculture squatters of Kalalau Valley are facing a final eviction

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/64/e3641e5d-4c96-4ff7-b270-60352d4a9484/header-outlaw-hippies.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The Neverland is always more or less an island, with astonishing splashes of colour here and there, and coral reefs and rakish-looking craft in the offing, and savages and lonely lairs, and gnomes who are mostly tailors, and caves through which a river runs, and princes with six elder brothers, and a hut fast going to decay, and one very small old lady with a hooked nose.

—J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan

The first person I meet in the Kalalau Valley is a shoeless veteran from the Iraq War with a sun-faded REI backpack slung over his tattooed shoulders like a trophy. Barca, as he calls himself, heard that a kayaker had abandoned the pack in a beach cave and made a beeline out to the bluffs to claim it.

Visitors are always just throwing stuff away in this place. Over here, a folding chair with a broken arm rest. Over there, a half-empty fuel canister. Now, the backpack—that’s a rare find. “Do you know how much these are worth?” Barca asks me.

In, like, dollars? Ten, tops.

“A lot!” he says without waiting for my answer.

Barca, who is 34, subsists as a scavenger deep inside the Nāpali Coast State Park on Kaua‘i’s west coast. The centerpiece of this 2,500-hectare park—the Kalalau Valley—forms a natural amphitheater that opens to the ocean and the ocean alone. The valley’s steep, green walls rise up on three sides like curtains, sealing it off from the island’s interior. Glassy threads of water are tucked into every crease of these walls, cascading down from a height greater than Yosemite Falls. First farmed by Polynesian settlers centuries ago, this remote paradise is nothing short of a feral garden, a breadbasket bursting with nearly everything a crafty human specimen needs to survive. “This is the closest that mankind has come to making Eden,” Barca says. “When the avos are in season, we eat avos. When the mangoes are in season, we eat mangoes.”

If you’re wondering whether he’s allowed to be living off the land here, the answer is no. Barca is a squatter in the eyes of the Hawaiian state government; he’s an eco-villain, a rule-breaker who needs to be eradicated. Barca, naturally, calls this slander. “If you don’t love this place with all of your heart, you couldn’t live here,” he says. Though he has only been a resident for eight months, which by valley standards makes him a relative newcomer, he’s already well on his way to becoming an expert in what he calls “Kalalau-ology.” He’s not only a trash recycler, he’s also a defender of the land, a gardener, a botanist, a cultural interpreter, and an anarchist-theorist. His tendency to grin and stroke his goatee when he’s talking gives him a puckish air, which underscores his antiestablishment streak. Spotting a group of tourists clambering across a stream in their pristine Gore-Tex boots, he is contemptuous. “Most of the people who come out here don’t know how to live in the woods,” he says. “They don’t even bury their shit!”

His rapid-fire diatribe is a lot to take in during my first five minutes in the valley, particularly since I’d woken up before dawn to hike the 18-kilometer trail to get here. At the moment, what I want more than a feast of mangoes or a discourse on backcountry sanitation is a place to drop my own pack, which I paid US $200 for and filled with a week’s worth of freeze-dried provisions (the horror). But where to sleep? Camping permits are hard to come by in Eden, and I hadn’t been able to get one before my last-minute trip, so, like it or not, I, too, would have to be an outlaw. I ask Barca if he knows any low-key spots to pitch my tent.

“Follow me,” he says, wrapping a kaffiyeh around his head to shield it from the sun. He needs to pick up an old cooking grate from another campsite and knows of the perfect hideaway for me. The next thing I know, he is off, bounding from rock to rock in his bare feet. To my right, I look down and dizzily watch the waves crashing over rounded stones more than 30 meters below. Next, we hug a boulder and Barca points toward a tunnel in the vegetation that leads to a campsite invisible to the rangers hunting squatters from helicopters.

After dropping off my things, Barca and I head down to the white sand beach and he unspools his life story. After a tour of duty in Iraq a decade ago, he struggled to make sense of the fact that he had killed people and had been nearly killed himself. “I had my issues when I got out,” he says.

He worked as an archaeologist in Northern California but realized that he was ill-suited to modern society. He felt as if his brain, rattled from his war years, needed a respite. He was repelled by the idea of walling himself off from his neighbors in a house in the suburbs or paying taxes in support of a system he no longer believed in. Even the idea of ordering a coffee each morning—from that multinational corporation with a mermaid logo—was too much. “It was hard to come back to the real world and take the minutiae of the day seriously,” he says. He’d get angry. He’d get drunk and fight. A friend told him about this dreamlike valley in Hawaii where you could live in the eternal present. Kalalau. He came. He stayed. “I don’t know if any place has felt this much like home to me,” he says, shortly before dropping his camouflage cargo shorts and diving into the surf.

Barca is not the only one who has felt such a bond with this place. Since at least the 1960s, the Kalalau Valley has been a magnet for long-haired hippies, crystal-stroking New Agers, deodorant-free backpackers, and others seeking a spiritual awakening—or at least a good place to skinny dip. During the Vietnam War, a group of draft dodgers and disillusioned veterans living in tree houses at the end of the paved road on the north coast realized that it would be the perfect place to grow marijuana in the summers.

It was the peak of counterculture activity, but as the years wore on idealism smacked into the messiness of society. This haven transformed from an idyllic retreat to a millennial party zone and an occasional pirate’s lair, and right now tolerance is wearing thin. After a local woman was killed when her car was hit by a fugitive named Cody Safadago who had spent some time in Kalalau last spring, the state launched a crackdown to clean out the squatters. They ticketed a total of 34 people last year and took at least one man out in handcuffs. Barca escaped unscathed. “I fucking live here and I know which way to run,” he says. “It’s my house and you’re not going to get somewhere in my house faster than I am.”

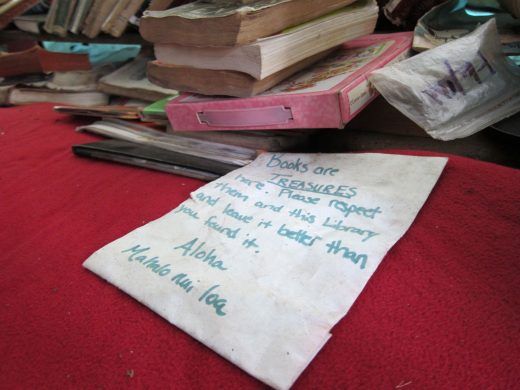

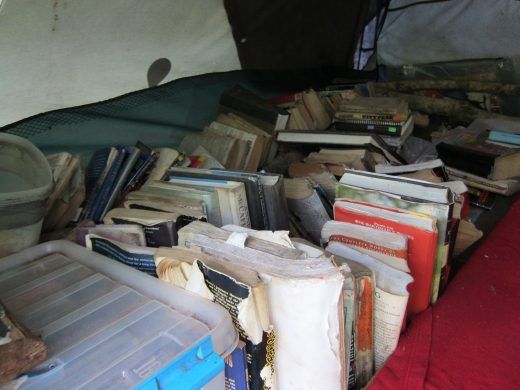

Sympathy for the squatters’ plight was scarce around Kaua‘i, however. Photos from the raids showed town folk just how elaborate the valley camps had become. One camp was outfitted with an earthen pizza oven and a queen-sized bed on a bamboo frame and contained what the state referred to, somewhat hyperbolically, as a “marijuana growing operation” complete with solar- and battery-powered lights. The valley also featured a secret movie theater and a library—a musty old tent filled with vintage treasures like The Joy of Partner Yoga and a book of Cat Stevens songs. All told, the state hauled out 2.5 tonnes of trash. “There’s a sense of entitlement,” Curt Cottrell, head of Hawaii’s state parks, told me. “People were crapping on archaeological sites and digging in the beach sand like cats.”

The uproar brought to the fore deep questions about race, sovereignty, and the future of the natural world in commodified, modern Hawaii. How can society benefit the most from a place like Kalalau with its complicated history? Do we give it over to the well-heeled tourists who book hiking permits six months in advance or pay $200 a person for 60-minute helicopter tours? Or does it still belong to the native Hawaiians who rarely visit, but whose ancestors were the first to shape the landscape? And what do you do about the haole (white) outlaws like Barca who, in their ragamuffin way, carry on the countercultural project of the 1960s and maintain some kind of order in a place with only an occasional government presence.

The one thing that is undeniable is that the valley is one of the most desirable places in the world for people who have practically nothing to take a break from the rules and rituals of modern life and eke out a simpler existence. Barca calls it a “Disney forest,” a tropical refuge devoid of venomous snakes or man-eating tigers, where almost everyone speaks English and looks pretty much like everyone else. Living here is like popping a Prozac each morning but without all the bad juju. A fruit smoothie for your soul—or something like that. All I know is I want to experience it before it’s gone.

There’s no easy way into Kalalau. The ring road that wraps around Kaua‘i has a 30-kilometer gap that is the Nāpali coast. For most of the year, the ocean is too rough to bring in a kayak. Motorized boats are forbidden, and the state has cracked down on locals offering an illegal water taxi service. Your best bet is to lug in supplies on the Kalalau Trail, which crosses five steep valleys and has been called “the most incredible hike in America.”

The cliff-side path also happens to be one of the world’s most dangerous. One wrong step at Crawler’s Ledge could send you careening into the sea. The many stream crossings are prone to flash flooding. At the three-kilometer mark on Hanakāpīʻai Beach, a white cross stands in honor of Janet Ballesteros, a 53-year-old woman who drowned there in 2016—the 83rd victim of its treacherous waters, according to a somewhat dubious tally on a sign there. Along with nature, you also have to contend with the people. In 2013, for instance, an Oregon man on a bad acid trip shoved his Japanese lover off a cliff.

Before my trip in July, it was hard to find information on how effective the raids really were and how risky it would be for me to head there. Mango, a former resident who had fled for greener pastures in Oregon, told me he was still getting text messages from a satellite communicator that the valley residents had at their disposal. I was surprised to learn that some of the most die-hard Kalalau outlaws were actually supportive of the rangers. “They are the predators culling the herd,” another regular visitor told me. “They are keeping the people in there strong and vigilant.”

My best bet for sneaking in undetected is to leave before sunrise one Saturday morning. As the first light breaks through the forest canopy, I pad my way down the trail and try to envision what this place was like before the squatters or anyone else set foot here. For one, I would have found little relief from the sun’s rays. The six-meter-high guava trees that now make up most of the forest were only introduced in 1825, and they quickly outgrew the native Hawaiian flora that featured a more open canopy.

In the late 1700s, when George Dixon, a British fur trader who once served under Captain James Cook, sailed along this coast, he concluded that it was barren of civilization. “The shore down to the water’s edge is, in general, mountainous, and difficult to access,” he wrote. “I could not see any level ground, or the least sign of this part of the island being inhabited.”

Dixon was, of course, mistaken. Thatched huts blend in well with the vegetation. In Kalalau, which offers about 80 hectares of agricultural terrain, the population likely numbered in the hundreds, according to subsequent missionary censuses. The oldest known human settlement on Kaua‘i, which dates to the 10th century, was situated at Kēʻē Beach—the starting point of the Kalalau Trail.

While the Nāpali coast is often described as a “wilderness,” the truth is it’s more like an abandoned supermarket surrounded by some epic scenery. The place is crisscrossed by stone walls, remnants of the terraced gardens, or lo‘i, Hawaiians constructed hundreds of years ago to cultivate taro, the principal “canoe plant” that Polynesians moved across the Pacific. These settlers gradually replaced the native forest shrub lands with kukui nuts and ginger, along with pili for their thatch roofs.

Later residents and white ranchers brought in livestock, including goats, pigs, and cattle, and planted the guava and Java plum trees that form most of the forest. “As in many lowland areas in Hawaii, introduced plants now form entire communities, dominating major portions of the park,” reads a 1990 report from Hawaii’s Division of State Parks. The Kalalau Valley, the largest valley in the park, is one of the few places on Kaua‘i where you won’t hear roosters crowing each morning. Instead, the forests are filled with another immigrant, Erckel’s francolin—a ground bird from Africa.

As the valley’s hodgepodge ecosystem took shape, it also began to develop its outlaw reputation. In 1893, after a group of American businessmen overthrew the queen of what was then the Kingdom of Hawaii, they decided to round up native Hawaiians under the auspices of a leprosy quarantine.

Sheriff Louis Stolz and two policemen headed out to Kalalau to remove one rogue band of lepers. There, a cowboy named Kaluaikoolau, or Ko’olau, shot the sheriff twice with a rifle, killing him, and became a hero of the native resistance. A bungled manhunt ended with more casualties and Ko’olau remained in the valley, unpunished, until his natural death two years later. “Free he had lived, and free he was dying,” the author Jack London eulogized in a short story about Ko’olau’s life.

Kameaoloha Hanohano-Smith, whose great-grandfather was part of the last generation to grow up in Kalalau, says it took a while for the Hawaiian people to understand what was happening to their culture. “One day we were a kingdom, and the next thing we knew we were part of the US,” he says.

In December 1959, Ebony magazine profiled the only permanent resident in Kalalau: a black physician named Bernard Wheatley (“a crank, a holy man, a schizophrenic and a genius”) who spent a decade living in a cave there until hippies started crowding him out. “Longhairs seek a place in the sun on Kaua‘i,” reads one headline from the time. The Hawaiian state government bought the property in 1974, and tried to evict the squatters before establishing the park in 1979, but they came back. They always come back.

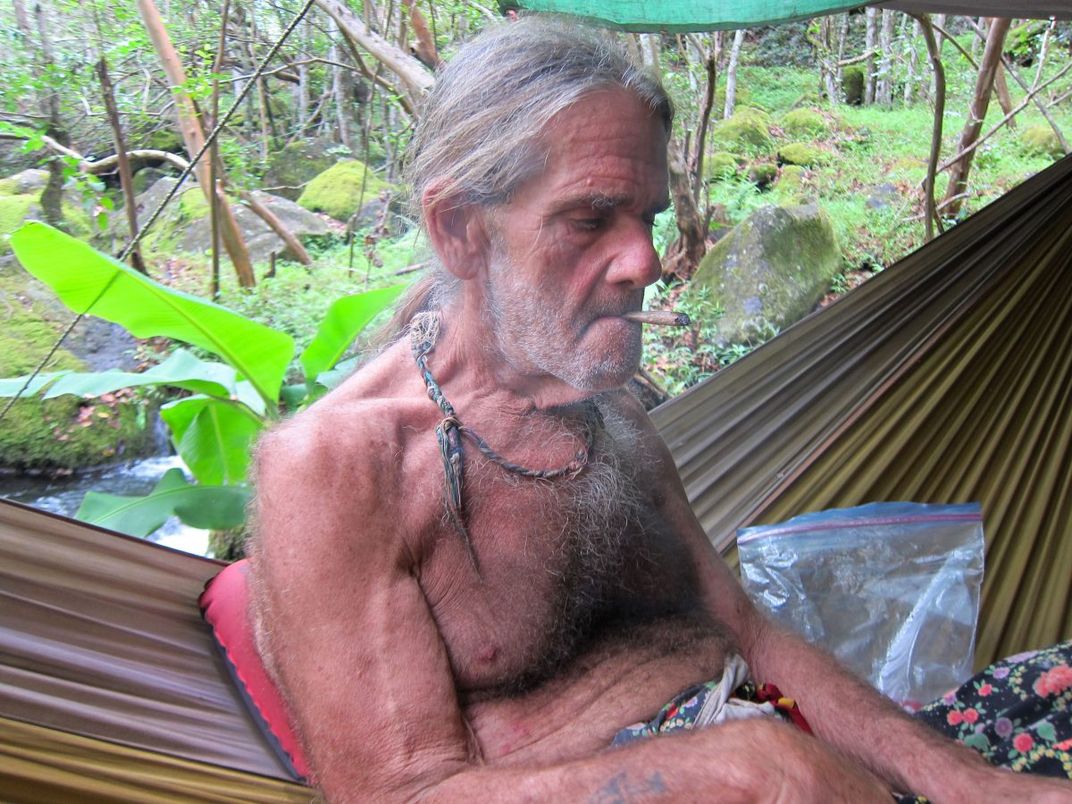

“We were free-minded people looking for a better place to live without the restrictions of society,” says Billy Guy, who first visited Kalalau after serving as an army medic during the Vietnam War and has returned for long stretches over the decades. “I’m fulfilling a dream.” By the mid-1990s, there were as many as 50 or 60 haole frolicking in a paradise that the kanaka—native Hawaiians—had created.

Freedom means different things to different people. While the hippies and latter-day outlaws may chafe under the norms of mainstream society, they still have to create their own rules for living together peacefully. The most that even the most hopeful can hope for is not a society without rules, but a tolerant one. And a tolerant place is bound to attract its share of misfits.

From the beginning, something seemed a little off about Cody Safadago. He had washed up in Kalalau last April with almost no possessions and had taken over a communal camp down by the beach. He was a rough-looking fellow in his early 40s with a buzz cut and two fleshy lips that hung on his face in a permanent scowl. Safadago had spent time in prison for beating his wife back in Washington State and, in 2014, was arrested in Belize after absconding from his parole officer and fleeing the country. He had been bumming around Kaua‘i since January at least, and had been arrested for disorderly conduct and assaulting an officer.

The people of Kalalau were wary of Safadago. He insisted, incessantly in almost every conversation he had, that he was God and everyone should bow down before him. “I talked to him for literally two hours,” says 30-year-old Carlton Forrest from Phoenix. “He was crazy, iced out beyond belief.” In the valley, it’s not easy to get help in the event of an emergency. The ranger station is usually empty, and cellphones don’t work here. The “family,” as the squatters sometimes call themselves, knew they needed to boot Safadago before something terrible happened.

A rangy outlaw in his 30s, who asked me to call him Sticky Jesus, began dismantling Safadago’s camp one morning. Befitting at least one part of his name, Sticky has long brown hair and a prophet’s beard. “You need to leave,” he ordered Safadago, who was sprawled out in a lawn chair.

Safadago opened his mouth to protest, making wild accusations about other residents. Sticky spun around and kicked him in the chest, knocking him out of the chair, according to an account described by Sticky and confirmed by other valley residents. “Can I just get my things?” Sticky remembers Safadago begging.

Sticky tossed a few of Safadago’s possessions his way and then pulled a flaming stick from the cooking fire and hit him with it as he retreated from camp. Safadago kept a low profile for a few days until he was ordered onto the back of a jet ski making an illegal drop-off and banished from the valley.

He wasn’t their problem anymore. At least that’s what they thought.

Safadago landed in the town of Kapa‘a, on the developed east side of Kaua‘i, where he got drunk and stole a Nissan pickup. He was driving over 140 kilometers per hour—three times the speed limit—when he crossed the centerline of the highway and struck a Mazda sedan head on. The young woman in the car, Kayla Huddy-Lemn, was pronounced dead at the hospital. Safadago stumbled out of the pickup—face covered in blood—and wandered up to a shopping mall, where he was arrested.

When a person dies like that, the whole island hears about it. About 50 kilometers in diameter, Kaua‘i is about the size of London and has a population of just over 72,000. As the news came out that Safadago had spent time in Kalalau, locals discovered a Facebook group called “Kalalau!” that appeared to show squatters moving stones from an ancient Hawaiian temple, known as a heiau, to divert water for farming projects. A hillbilly hippie named Ryan North (alias: Krazy Red), who spends a few weeks there every year, posted trippy videos of himself saluting the camera while bare-chested white women danced in hula skirts.

“Bitches, this has nothing to do with race. It just so happens all of you fucked up, selfish Kalalau hippies are white,” one angry Hawaiian vented in a social media post.

Some observers complained that the squatters were collecting food stamps, known as electronic benefit transfers, to support their hedonistic lifestyle (true). Others argued that the place had become a breeding ground for sketchballs (sorta true). “You just don’t know who could be hiding out in Kalalau,” a woman named Kristi Sasachika told a local reporter. The vitriol was so worrisome that the Garden Island newspaper published an editorial warning locals against a “vigilante mindset.”

Long-term residents say that it’s not fair to lump them in with the careless partiers who often get dropped off by boat with a case of beer and a pile of Walmart camping gear they’ll probably leave behind. As in any society, there are good actors and bad ones. Kamealoha Hanohano-Smith, one of the locals with a genuine tie to the land, also takes a more measured tack. “I have a lot of aloha for people whether they are haole or whatever,” he told me over the phone. “I understand why they want to be there. They would love to believe they are appropriate stewards of the area, but the better thing would be for them to work with Hawaiian families.”

**********

On my second morning in Kalalau, I decide to go looking for the community garden. Starting at the beach, there’s an official trail that heads about three kilometers up the valley before hitting the steep back wall. It’s possible to walk up and down that trail a few times before you notice an unmarked spur off to one side.

Follow it for a hundred meters and the forest canopy opens up and you can hear a trickling at your feet. A dozen rectangular ponds glisten in the sun, meter-high taro plants sprouting from their waters. Paths leading around the ponds are lined with papaya, banana, jackfruit, soursop, and chestnut trees—all free for the taking. Squatters were once expected to do some work if they wanted to gather some fruit. But things are different now. “There aren’t any rules anymore,” says a resident named Mowgli, who offers to give me the tour.

Slender and muscular with his long brown hair pulled back into a ponytail, Mowgli helped restore these flooded terraces, and is one of the hardest workers in Kalalau. His former camp, which sits on a plateau nearby, gives off a Lord of the Flies vibe, decorated with dozens of skulls from the goats and pigs he has slaughtered. The raids broke him. “It’s hard to focus on something when they want to take it apart,” he says. “This is one of the big tourist attractions in the valley,” he says of the garden.

“People want to come and see us and have Kalalau pizza,” says Mowgli’s female companion, whose only article of clothing is a baseball cap. She calls herself Joules. “Like the energy unit,” she explains.

I had given myself five days to explore the valley and immerse myself in the hippie-sphere. With a few notable exceptions, I learn that women like Joules rarely stay more than a few weeks in the valley, and, for whatever reason, they had become particularly scarce in the aftermath of the raids. At least during the time I was there, the testosterone surplus made the place feel less like a utopian kibbutz and more like a secret tree fort in your buddy’s backyard where girls are little understood or respected. Except these guys are adults. One offensive song I heard performed one evening referred to the “drainbow bitches” who “don’t do the dishes” after stopping in for a free meal. The men, nevertheless, longed for female company. “A woman who does stay has 10 guys trying to find her every day,” a 68-year-old bachelor named Stevie told me, drawing from his 35 years’ experience in the valley.

One evening, I sit with six other guys under the enormous mango trees at a camp maintained by a guy named Quentin. A bearded, genial host with a self-effacing manner, Quentin landed in Kalalau after his dream of making marijuana chocolates fizzled. “It was overwhelming,” he says of his failed attempt at capitalism. He tried to live out here with his girlfriend, but she couldn’t deal with the mosquitoes. “I started building things to make it more comfortable for her, like the cabinet by my bed,” he says, gesturing toward a bamboo console. “But really, she just didn’t like me.” She ended up hooking up with another guy in the valley—Sticky Jesus—when they were both back in town. “I really wanted to punch him in the face, and I even flicked him off once,” he says.

There was one tense evening when I thought a physical fight really might break out between two of the guys. I watched the only woman present slip away and head back to her tent. When I asked her about it later, she said it wasn’t the kind of experience she was looking for in Kalalau. The boys, she said, were lost in “never-never land.”

It’s remarkable that even in a place like Kalalau, people still get wrapped up in the same petty dramas they face living within four walls and with roofs over their heads. Paradise is never lost because it can never be found. People are jealous. They’re selfish. Thoughtless. Humans create societies for a reason. They create rules for a reason. A limited kind of social contract may exist in a place like Kalalau when few people are visiting and living there, but it easily frays in times of stress.

And as much as Kalalau—or the idea of Kalalau—means to the squatters, they are far from the only people who have a stake in its future.

Sabra Kauka, an educator in Hawaiian culture and past president of the Nā Pali Coast ‘Ohana, a nonprofit that works with the state to protect the valley’s natural and cultural heritage, says people like Quentin and Barca and Mowgli should not be living in Kalalau. It’s against the law and it’s an insult to the Hawaiian people. In the late 1980s, Kauka took part in early efforts to clean up the valley. She and a group of volunteers would haul rubbish down to the beach and load it into slings that helicopters would carry away. “It stunned me that people who wanted a wilderness experience would be so insensitive,” she says. At a certain point, she simply gave up. “You do not want to do volunteer work that makes you angry.”

A state parks archaeologist, Alan Carpenter, told her about a 14th-century village site along the shoreline, Nualolo Kai, accessible only by boat and fringed by the largest reef on the Nāpali coast. For the past 25 years, Nā Pali Coast ‘Ohana has focused almost all of its work at that site. They built fences to keep out goats and established a small native garden to preserve some of the region’s biodiversity. Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, they have even brought back the remains of ancestors who were housed at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu and other repositories.

Now, under the auspices of Randy Wichman, a historian and the organization’s current president, they are finally making plans to bring their work back to Kalalau. Whether they can succeed in a place where they failed in the past remains to be seen. Wichman expresses some grudging admiration for the squatters’ ingenuity in terms of the work they’ve done on the lo‘i’s, but he says that some of them have done more harm than good. “Their intentions are good, but you obliterate history by not knowing exactly what you have,” he told me. “The valley would be stunning if it were in working order.”

**********

In 100 years, when their tarps have rotted away and their footpaths have been lost to the forest, I wonder what place the outlaws will occupy in the grand story of Kalalau. Though reviled in some quarters, their ethics questionable at times, the outlaws’ reign demonstrated to the modern world the power of place to the collective psyche. The vulnerable, confused, damaged often end up here, to heal and to grow before they rejoin the world. It’s kind of wonderful. “We’re tool-using monkeys,” Barca told me when I first met him. Being part of an interdependent community like Kalalau feeds a deep primate urge. “Biologically necessary,” is how he put it. More necessary for some than others.

The head of state parks, Curt Cottrell, told me that when he first moved to Hawaii in 1983 as a “bearded hippie guy,” hiking the Kalalau Trail was one of two goals. (The other was hiking to the summit of Mauna Loa.) When his permit expired, he evaded the rangers by swimming a few hundred meters south to Honopū, the next cove over, for a day. When I ask him if one day the park will find a way to commemorate the hippie occupation, he offers a careful response. “We have no desire to erase that history,” he says, “but at this point in time, we don’t feel like celebrating it until we get the place cleaned up.”

That may not be so easy. The agency has 117 staff members spread out over Hawaii’s 50 state parks. Kalalau is a priority, but there are so many places for squatters to hide that it’s impossible to kick them all out. The agency had asked the legislature for enough money to have two full-time staff members inside the park. Their request was denied.

Kalalau is already a very different place than it was just a few years ago. It’s undoubtedly the cleanest it has ever been. And apart from the intimate gatherings I’d witnessed up valley, the place had the feel of a ghost town. I spend my days exploring overgrown footpaths from one clearing to another, looking for abandoned campfire rings and other traces of recent human habitation. Even the official campsites were largely empty, hosting no more than 20 or 30 tourists each night while the state allows 60. Though native Hawaiians do visit and hunt inside the park, I met only outlaws during my visit.

Hanohano-Smith, who can trace his family back to the valley, says that he’d like to see regular Hawaiians—not just the state—playing a larger role in the future of Kalalau. He believes that his family should have free access to visit the land without vying for scarce permits and that Hawaiians should be able to benefit from it through jobs, possibly as teachers or guides. “It’s not just an issue of sustainability,” he says. “It’s the pride associated with being connected to the resources that provided for my family 1,000 years ago.”

On one of my last mornings in Kalalau, I see Sticky Jesus and Stevie loading their things onto a kayak on the beach. Stevie, the oldest resident out here, hasn’t been staying in the valley as often as he used to. Five years ago, he qualified for low-income housing and has a small home down in Kekaha. He loves Kalalau but at some point he knows he’ll be too weak to hike in or to take care of himself.

For Sticky, the story is a little more complicated. He is going to live in a van with Quentin’s ex-girlfriend and try to make a little money. I’m not sure if he’s going to come back, and I say as much. “I’ve got a house here still,” Sticky replies. “Most of it got taken a couple weeks ago, but I’ve got a good feeling about it.” He likes being free of his possessions.

“You didn’t take it as hard as Mowgli?” I ask.

“I don’t take anything as hard as Mowgli,” he says.

The two squatters hop into the kayak and Carlton gives them one last shove into the knee-deep water. We stand there for a few minutes, watching them disappear around the red bluffs to the south, and then I head back up the trail into the valley. I’m not ready to hike out just yet. I’m not looking forward to pulling out my wallet and paying for a piece of produce with a sticker on it when the fruit out here will drop to the forest floor and rot away without someone here to harvest it. I just need one more day living as an outlaw in the Kalalau Valley. Maybe two.

Related Stories from Hakai Magazine: