Hawaii’s Must-See Lava Flows Are Home to New, Startling Ecosystems

These stunning volcanoes are creating new islands of evolution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/ad/18ad19ed-23dd-44b9-8c0d-a25af186541a/apr2017_e13_hawaiinationalpark.jpg)

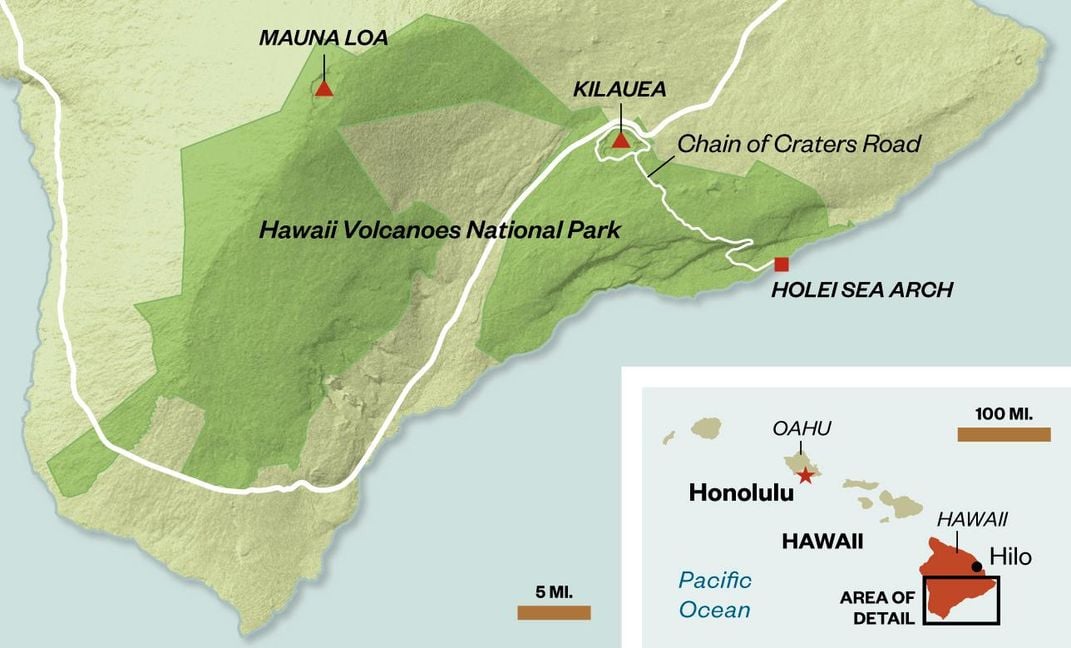

Volcanologists have a flair for understatement. Here is the term for the roiling, spattering 2,000-degree Fahrenheit liquid rock visible in the caldera of Kilauea volcano this afternoon: lava lake. As though, had I a more powerful pair of binoculars, I could make out rowboats and little people picnicking on the shore. I forgive the volcanologists, because no words I know adequately capture the beautiful, violent strangeness of molten lava. You can see Kilauea’s churning “lake” from overlooks in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, and you can watch its lava tubes bleed into the ocean several miles southeast.

For all these reasons, Kilauea is the park’s star attraction. But don’t overlook Mauna Loa (also active but currently “in repose”). Mauna Loa has the kipuka trails. Kipukas have been described as living laboratories for evolution. They’re pocket forests isolated by lava flows that went around them instead of over. Sometimes the greenery was spared because it was at a higher elevation than the surrounding terrain, and sometimes it just got lucky. Members of species that used to share turf and swap genes got separated by Nature’s igneous paving crews. If the environments in their respective kipukas differed, they adapted to the local conditions and began to evolve separately. Drift far enough genetically, and you become a new species. Kipukas help explain Hawaii’s extraordinary rate of speciation. From as few as 350 insect and spider colonizers, for instance, Hawaii now has 10,000 species. Six original colonizations of bird ancestors have become 110 species. And because lava flows are easily datable, scientists can look at two closely related species and know which evolved from which. Hawaii, one scientist wrote, “is God’s gift to the evolutionist.”

Steve Hess, a wildlife biologist who works out of the Kilauea Field Station of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, offered to show me around a couple of kipukas alongside the Kaumana Trail, on Mauna Loa’s eastern flank. (Nearby Puu Oo Trail also traverses kipukas.) A lot of the evolution research done here has focused on drosophila—fruit flies. In part, this is because they’re short-lived. A generation comes and goes in a couple of weeks, so evolved traits show up much more quickly than they would in mammals. And drosophila are poor fliers, rarely commuting between kipukas. From one (or a few) original immigrants from Asia, Hawaii now has as many as 800 drosophila species. (And seemingly as many drosophila researchers. The Hawaiian Drosophila Project, begun in the 1960s, is still going strong.)

Kaumana Trail is an easy hike, winding over broad, rounded moon pies of pahoehoe lava. (Pahoehoe’s Scrabble-friendly cousin aa—a sort of knee-high stone popcorn—is also plentiful in the area, but challenging to hike.) Though the vegetation along the path is sparse, there’s abundant beauty in the contrast of the black lava and the bright greens of the shrubs and grasses that manage to take root in the organic debris that settles between mounds of pahoehoe. Other than a few six-foot ohia trees, we’re the tallest organisms on the trail. Hess points out Hawaiian blueberries, which are less blue (they’re red) than other states’ blueberries.

After 15 minutes of hiking, a stand of older-growth ohia trees appears on our right: kipuka! Although it’s small (about nine acres) and no sign marks the boundary, it’s not hard to locate. It’s like when my husband takes the clippers to his hair. Hey, Lava, you missed a spot. As we push into the interior, tree ferns come into view and thick undergrowth slows our travel. We no longer see lava underfoot, because it’s buried under 3,000 to 5,000 years of rotted logs and leaves. It’s just a lot messier in here. I look up to see a blue kitchen sponge attached to the trunk of an ohia tree, as though someone else had had that same thought. Hess explains that researchers soak the sponges in yeasty water to attract fruit flies, then return a couple of hours later with an aspirator to suck them up for study. The sponges are supposed to come down when the project ends, not just because they’re eyesores, but because leaving litter in the forest is disrespectful. Deities of Hawaiian mythology can take the form of natural elements, including the forest itself (the god Kamapuaa) and lava (the goddess Pele). This explains the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park signage admonishing visitors, “Do not roast marshmallows over lava (Pele).”

Shade inside the kipuka makes it appreciably cooler than out on the lava fields. It’s also noisier in here. Kipukas provide food and housing for more than half a dozen vocally energetic endemic bird species. Flocks of scarlet-red apapane—honeycreepers—keep up a whistling chitter-chatter. The songs differ subtly from one kipuka to another. I had hoped to be able to hear these honeycreeper “dialects” in the kipukas we’re visiting today, because the differences predate speciation. From the honeycreeper ancestors that arrived in Hawaii between five million and six million years ago, at least 54 different species have evolved. Hess explains that to make out the differences, I’d need to look at spectrograms: visual representations of frequency, pitch and loudness—a sort of EKG for bird song.

This I do on a different day, at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, in the bioacoustics lab of biologist Patrick Hart. Because the material under study is sound, the lab lacks the more stereotypical trappings of biology. No microscopes or autoclaves, just computers arranged in two long rows. Hart stops in while I’m there, and I ask him to clear something up for me. Given that birds can fly from kipuka to kipuka—that is, they’re not isolated like plants or snails, or weak fliers like drosophila—why have they speciated so dramatically?

Let’s say a population of apapane is split apart by lava flows, Hart begins. Even though the birds are able to fly to each other’s kipukas, they spend far more time in their own. Like New Yorkers in different boroughs, they start to develop distinct accents or “slang,” if you will. When an apapane does travel to a distant kipuka, she may not recognize the locals’ song. This is key, because bird song is the first way a female apapane judges a male’s appropriateness as a mate. He may talk a good talk, but she doesn’t know what he’s saying. Genetically the pair are still viable—they’d be able to produce offspring—but behaviorally they are not. They’re never going to hook up. Soon (evolutionarily speaking) the birds of these two kipukas will diverge sufficiently to be classed as separate species. In this way, kipukas may drive—and help explain—the rapid speciation of Hawaiian birds.

Hart’s colleague Esther Sebastian Gonzalez showed me her glossary of hand-drawn notations for 348 different syllables sung by one species of apapane. They are like hieroglyphs of unknown meaning. Although she can’t translate them, she knows they are not random. One grouping of syllables may allow members of a flock to keep track of each other in the leafy kipuka canopy. Others may be warnings, flirtations, a tip. Don’t leave without me. Feral cat! Awesome nectar here. Some jerk left a sponge in my yard.

**********

The Kaumana Trail makes it easy to be one of those annoying hikers who can call out the names of every plant species they pass. Out on these lava fields, there are a dozen or so native ones. This is everything Kamapuaa has managed to create in the 150-plus years since Pele poured through here.

Hawaii’s ecosystems are isolated enough—and thus simple enough—that ecologists can recite the typical order of arrival on new lava. Lichens appear first, needing only air, moisture, rock. Dead, decomposing lichens form the paltry substrate that enables everything else to get established. Moss and ferns are early settlers, as well as the extremely undemanding ohia tree, which makes up the majority of the biomass in any native Hawaiian forest.

The leaves and red spiky stamen and other detritus the ohia drops and the shade it provides set the stage for the next wave of plant life: club moss, grasses, shrubs. This is why there’s so much concern about a new fungal disease called rapid ohia death—why, as Hess puts it, “Everyone’s screaming with their hands in the air. The landscape as we know it is driven by this species.”

The simplicity of Hawaii’s ecosystems is another reason it attracts researchers. It’s easy to isolate the effect of, say, a rise in one species population on another. “In a place like Costa Rica,” Hess says, “it’s just a huge mass of hundreds of species.” It’s too complicated to know what’s causing what with any degree of certainty.

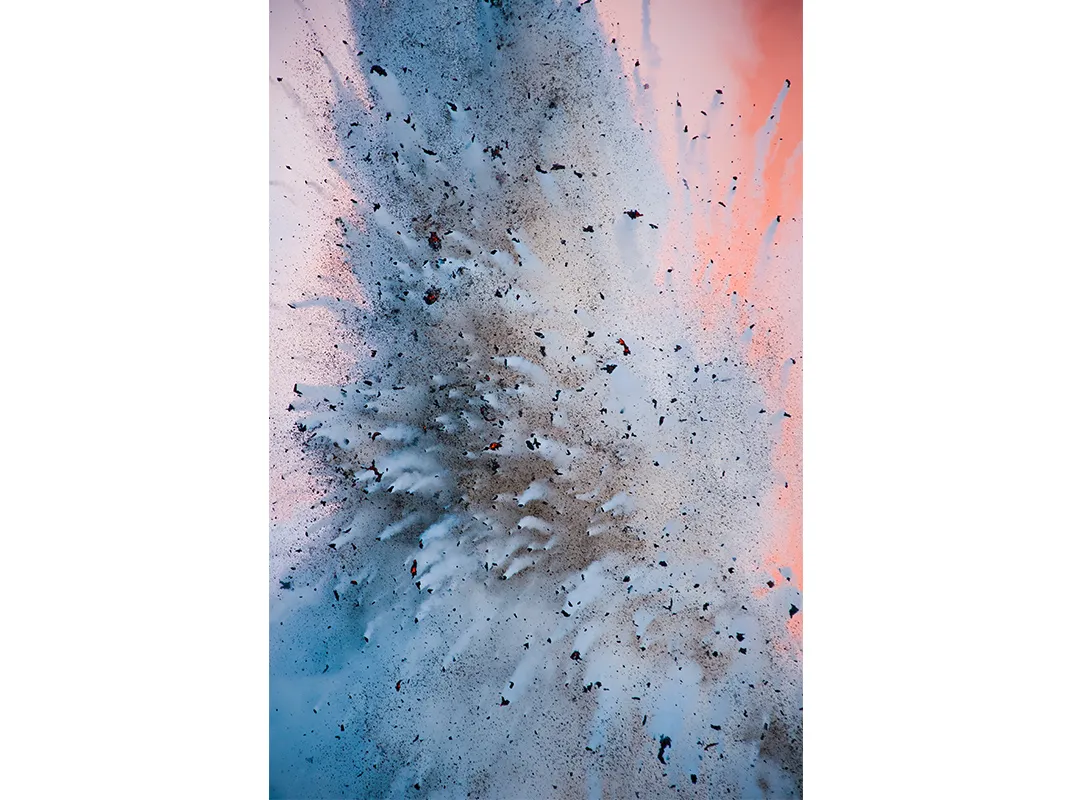

There’s beauty in Hawaii’s simplicity, not only for the ecologist but for the traveler. The day I arrived, I rented a bicycle and rode out to the point along the coast where some of Kilauea’s newest lava tubes ooze their contents into the ocean. (As a lava flow cools, it forms a tubular crust that insulates the lava inside and keeps it hot enough to continue flowing.) The gravel road cut through the simplest ecosystem of all: the rippling brownie-batter plains of Kilauea’s recent flows. No kipukas out here: just mile upon mile of the black undulations formerly known as magma. A postcard from earth’s unfathomable innards. With the white-capped cobalt water beyond, the scene was both breathtaking and apocalyptic.

For half an hour I sat on a bluff watching molten lava transform seawater to a fast-billowing steam cumulus. As the lava cools and hardens, the island extends itself, minute by minute. This is the process by which all of Hawaii was formed. Just as stepping into a kipuka on the Kaumana Trail allows you, in a few footsteps, to go from an ecosystem 162 years old to one that’s 5,000 years old, here you are time-traveling tens of millions of years. It’s hard to imagine a more awesome trip.