Four Surprising Places Where Local Wines Thrive

Almost everywhere European explorers went, vineyards grew behind them. Here are a few places tourists might never have known there was wine to taste

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121011121107WineGuadalupeSMALL.jpg)

Where men have gone, two things have almost inevitably tagged along: rats—and grapevines. The one sneaked aboard the first boats to America, living on crumbs and destined to swarm a whole new hemisphere as surely as the Europeans themselves. The other was packed along in suitcases, lovingly so, and with the dear hope that it would provide fruit, juice and wine just as readily as it had in the motherland. And the grapevine did. When the Spaniards hit the Caribbean and spread through Mexico, vineyards grew behind them like cairns marking the trail of a shepherd. Vitis vinifera struggled in the muggy Southeast, but Mexico and Texas became centers of wine production, as did California, south to north along the Catholic missionary route. Meanwhile, the common grape went about rooting itself in the rest of the world. Just as the Phoenicians had introduced the species to Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula millennia ago, sailors of more modern days brought their wine vines to southern Africa, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. The species thrived in Chile, produced super crops in the Napa Valley and gained fame in the Barossa Valley of Australia.

Like rats and men, V. vinifera had conquered the world.

Today, the expansion goes on. New wine industries are growing in old places like Central Africa and India, while old industries are being newly discovered in Baja California and Texas. In China, ballooning into a hungry giant in a capitalist world, winemakers are cashing in on the thirst for the world’s favorite funky juice. And in England, they’re cashing in on the grape-friendly effects of global warming. From the high mountains of the Andes to the scorching plains of equatorial Africa, grape wine is flowing from the earth. Following are a few places where tourists might never have known there was wine to taste.

North Carolina. Once among the leading wine-producing regions in America, North Carolina saw its industry wither when Prohibition kicked in, and for decades following, it lay in ruins, grown over with tobacco fields and mostly forgotten. But now, North Carolina wine is making a comeback. Twenty-one wineries operated statewide in 2001, and by 2011 there were 108. Many make wine from a native American grape called muscadine, or scuppernong (Vitis rotundifolia). The drink is aromatic and sweet—and supposedly dandier than lemonade on a warm evening on the porch swing. But familiar stars of the V. vinifera species occur here, too. RayLen Vineyards makes a knockout Cabernet-based blend called Category 5, named to honor the high-octane cyclone that was bearing down on the coast just as the family was bottling a recent vintage; RagApple Lassie‘s red Zinfandel is tart and zesty like the classic Zins of California; and Raffaldini Vineyards and Winery runs the tagline, “Chianti in the Carolinas,” with Sangiovese and Vermentino its flagship red and white. A good starting point for a tasting tour is the city of Winston-Salem, gateway to the Yadkin Valley wine country. Also consider visiting the Mother Vine. This muscadine grapevine first took from a seed circa 1600 on Roanoke Island. Generations of caretakers have since come and gone while standing guard over the Mother Vine, whose canopy has at times covered two acres and which barely survived a clumsy pesticide accident in 2010 during a roadside weed-killing outing by a local power company. Want to taste the fruit of this old lady? Duplin Winery makes a semisweet muscadine from vines directly propagated from the Mother Vine herself.

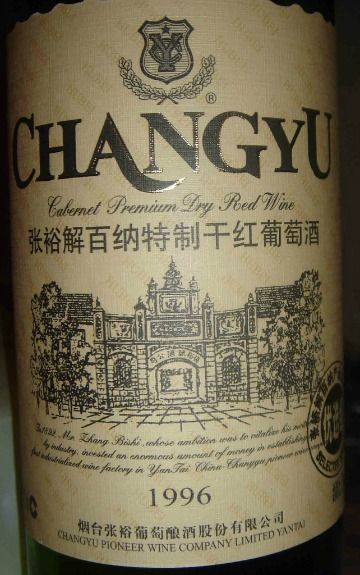

China. In parts of China’s interior wine country, grape varieties that evolved comfortably in sight of the Mediterranean Sea shiver as autumn plunges into the sub-Siberian winter. To keep their vines from dying, Chinese farmers must knock them over after harvest, bend them to the ground, bury them under 15 inches of dirt and hope to see them again in the spring. The method, though laborious, seems to work well enough, and the wines of the central province of Hebai have spawned the flattering regional nickname “China’s Bordeaux.” But the nation’s modern wine industry took a humiliating hit in 2010 when six people were detained in connection with the discovery of dangerous chemicals—used for flavoring and coloring—in a number of big-name Hebai wine brands, including Yeli and Genghao. Around the nation, retailers cleared their shelves of suspect bottles—many falsely labeled as high-end products, and some containing just 20 percent real wine. Worse, some wine bottles (2.4 million per year) from the quote-unquote “winery” Jiahua Wine Co. contained no wine at all—just a masterly handcrafted mélange of sugar water and chemicals. But thirsty travelers must have a drink now and then, and if you’re not in Rome, well, you might just have to drink what the Chinese drink. Thankfully, this country knows wine. Really. Evidence of indigenous winemaking dates back 4,600 years, prior to V. vinifera‘s appearance, and today China is gaining a reputation as a producer of serious wines. (“Serious” is the oenophile’s way of saying “good”—though one must note that “playful” wines can also be good, if not serious). Consider Chateau Junding, Changyu Winery and Dragon Seal, among other wineries.

Baja California. From the tip of the Baja peninsula to the United States border, vineyards grow in desert canyons watered by springs and shaded by date palms and mango trees, and travelers who inquire with locals may easily find themselves soon enough in possession of a Pepsi bottle freshly filled with two liters of red, semi-spritzy, alcoholic juice. But it’s in the northern valleys of Guadalupe, San Vicente and Santo Tomás that tourists find the serious stuff—wines so fine and fussy they demand glass bottles with corks and labels. In fact, among the sorts of people who talk about particularly great vintages of the 1960s, and certain Pinots that are just peaking, or whether a Bordeaux might benefit from being “laid down” for a few more years—the wines of Baja are gaining a classy reputation. The fierce heat of Baja’s summers is the driving force behind a range of excellent red wines. Look for Rincon de Guadalupe’s Tempranillo, a jammy, forceful wine with some delicious upfront scents of bacon and smoke. And the Xik Bal Baja Cabernet Blend is as vigorous and elegant as the prized Cabs of the Napa Valley. Want a white wine? The Nuva, from Vinicola Fraternidad, is a fruity, fragrant combo of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Moscato de Canelli. For a taste of history, visit Bodegas de Santo Tómas, the oldest winery in Baja. You might also try and track down a bottle of Criolla (also called Mission), the first grape variety the Catholic missionaries introduced so long ago.

India. Grapevines enjoy a winterless wonderland in the tropical wine country of India. That is, they would enjoy it if their keepers didn’t induce the dormancy of the deciduous vines by hacking them down each spring. “See you after the monsoon,” says the farmer to his stumped vines, and he walks away with his rose clippers to tend to his cashew and mango trees. If he didn’t cut them back, the vines would thrive all year and even produce two crops—each a halfhearted, diluted effort from the vine, which really needs several months of hibernation each year to perform best. And when the rains have passed, buds sprout and blossom, and as the leaves unfold into the sunlight, miniature bunches of grapes appear and begin their steady surge toward ripeness and the season of harvest—which, in this topsy-turvy tropical land, happens in March, even though it’s north of the Equator. Bizarre. Sula Vineyards is one of the more famous wineries in the state of Maharashtra, with Shiraz, Zinfandel, Merlot and Sauvignon Blanc among its main varieties. Other nearby sipping sites along the Indian wine-tasting trail include Chateau Indage, Chateau d’Ori and Zampa Wines. But things don’t smell quite like roses in India’s wine country. Though production grew steadily for years, with Maharashtra’s wine grape acreage ballooning from roughly 20 in 1995 to 3,000 in 2009, the market took a hard hit in 2010. Bad weather and economics were the main culprits, though some reports say the industry is stabilizing again. Still, Indians seem not to be developing a taste for wine like Westerners have. While per capita wine consumption runs 60 to 70 liters per person in France and Italy, according to this article, and 25 liters in the United States and four in China, the average Indian drinks between four and five milliliters per year—just enough to swirl, sniff, taste and spit.

Next time, join us as we explore more unlikely regions of wine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)