When Colorado Was (And in Many Ways Still Is) the Switzerland of America

A hundred years ago, city slickers looking for wild times in Rocky Mountain National Park invented a new kind of American vacation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/7e/8f7ed7db-786d-4750-b2cb-494892b530a3/jun2015_h06_colorado.jpg)

Back in the 1870s, when American travelers imagined the West, they didn’t picture the desolate plains and cactus-strewn mesas so beloved by John Ford. They thought of somewhere far more sedate and manicured—a place, in fact, that looked surprisingly like Switzerland. For the restless city slickers of the Gilded Age, the dream destination was Colorado, where the high valleys of the Rocky Mountains, adorned with glacial lakes, meadows and forests as if by an artist’s hand, were reported to be the New World’s answer to the Alps. This unlikely connection with Europe’s most romantic landscape was first conjured in 1869 by a PR-savvy journalist named Samuel Bowles, whose guidebook to Colorado, The Switzerland of America, extolled the natural delights of the territory just as the first railway lines were opening to Denver. Colorado was a natural Eden, Bowles burbled, where “great fountains of health in pure, dry and stimulating air” lay in wait for Americans desperate to escape the polluted Eastern cities. Artists such as Albert Bierstadt depicted the landscape with a celestial glow, confirming the belief that the West had been crafted by a divine hand, and as worthy of national pride as the Parthenon or Pyramids.

Soon travelers began arriving from New York, Boston and Philadelphia in walnut-paneled Pullman train coaches, thrilled to stay in the Swiss-style hotels of resort towns like Colorado Springs, where they could “take the waters,” relax, flirt and enjoy the idyllic mountain views. Pikes Peak became America’s Matterhorn, Longs Peak our answer to Mont Blanc, and the chic resorts at Manitou Springs evoked glamorous European spas. (So many rich invalids arrived in the resort that the common greeting between strangers became, “What is your complaint, sir?”) These pioneer tourists were far more interested in the scenery than local culture: One visitor was delighted to report, “So surrounded are you by snowy summits that you can easily forget you are in Colorado.”

The reality was that Colorado (which was a territory from 1861 to 1876, then entered the Union as a state) was still very much a raw frontier, which adds a surreal element when reading travelers’ letters and memoirs. Eastern swells found themselves in the raucous saloons of Denver, rubbing shoulders with gold miners, trappers and Ute Indians, while hard-bitten mountain men wandered the same “alpine” trails as genteel sightseers. So much of the Rockies had yet to be explored that one governor boasted he would name a new peak after every traveler who arrived. And the repeated insistence on European connections, to distract from rougher social elements, could border on the fantastical. Boulder, for example, was “the Athens of Colorado.” Local wits began referring to Switzerland as “the Colorado of Europe.”

While many travelers shied away from Colorado’s wild side, keeping to their grand tour schedules of French banquets served by liveried waiters, a small but influential group of hikers, hunters, artists and poets embraced it. Qualifying as America’s first adventure travelers, these vigorous characters—well-heeled nature lovers, heiress “lady authors,” Yale college students on a shoestring budget—braved dust-filled stagecoach journeys that lasted for days on end, and survived raunchy Western inns. (One 1884 American travel pamphlet, called Horrors of Hotel Life, is a hypochondriac’s nightmare, warning of verminous beds, ice pitchers that had been used as spittoons and towels “stained, soiled, poisoned with unmentionable contagion.”) In dusty towns like Durango, local lore has it, gents would scramble unseen through networks of tunnels to visit red light districts. Seemingly immune to physical discomfort, the travelers hired crusty Western guides in buckskin jackets, then embarked on horseback camping trips with nothing but a sack of flour and side of bacon in their saddle pouches. They hunted elk and deer, and dined on exotic Coloradan delicacies, such as beaver tail, bear steak and broiled rattlesnake. They were lowered by rope into hot “vapor caves” with Native Americans, and scrambled in hobnailed boots and bustle dresses to dangerous summits, all to experience what Walt Whitman (a Colorado fan after his 1879 tour) called “the untrammel’d play of primitive Nature.”

Along the way, they met Coloradan eccentrics, such as the Prussian Count James Pourtales at the resort of Broadmoor, where guests would “ride to hounds” in the English style, pursuing coyote instead of fox. There was Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, the 4th Earl of Dunraven, an Irish aristocrat with a prodigious mustache who “roughed it” all over the Rockies and wrote a best seller on their raw pleasures.

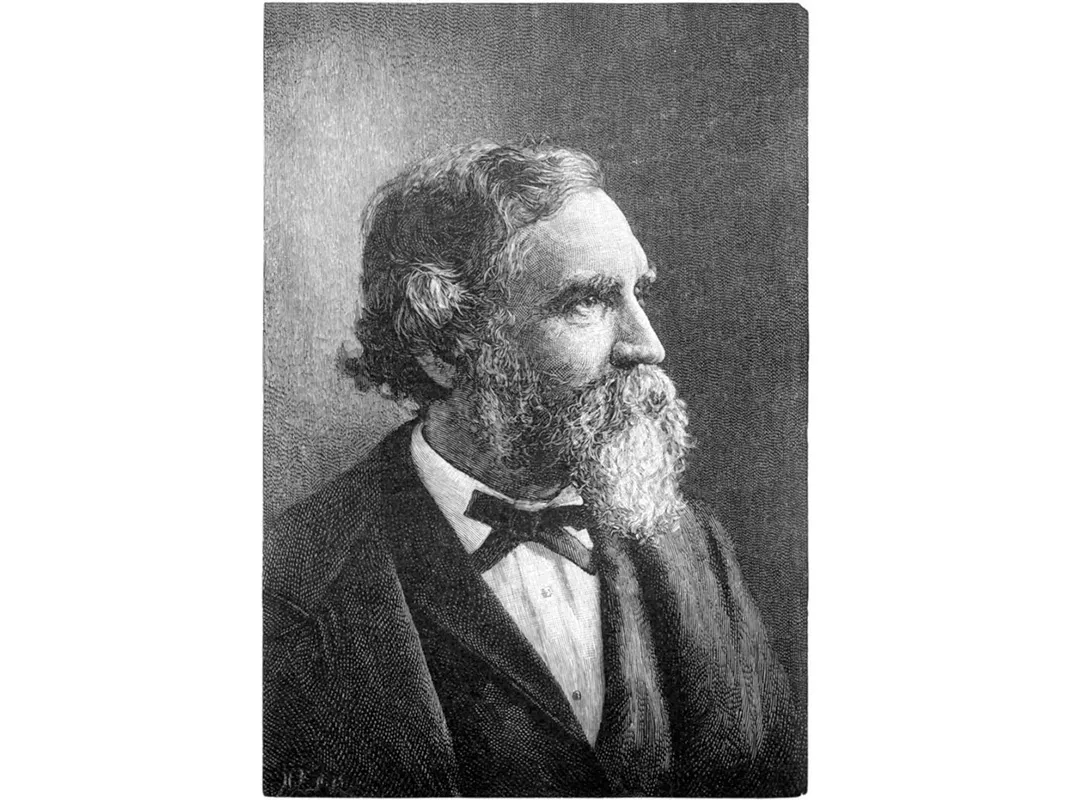

And some adventurers found love. One of the most unlikely holiday romances in American history blossomed in 1873, when a prim Victorian writer named Isabella Bird met a drunken frontiersman known as “Rocky Mountain Jim” Nugent. While some of the more intimate details are still the subject of speculation, the two certainly made an extravagantly odd couple in the spirit of The Ghost and Mrs. Muir. (In fact, if Odd Couple author Neil Simon ever wrote a western comedy, he might draw inspiration from Bird’s memoir, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, or her letters to her sister Henrietta, which reveal her unedited emotions.) The English-born Bird was a striking sight in the Colorado Territory, a 41-year-old woman, considered a spinster in that era, riding alone on horseback in Turkish bloomers, a heavy blouse and broad-rimmed hat, a costume that sometimes gave her (she admitted) “the padded look of a puffin.” She covered 800 miles, but her goal was Estes Park, a valley settlement high in the Rockies that was gaining a reputation among travel insiders as the most spectacular spot west of the Mississippi. It was so remote that it took Bird several tries to find it.

Finally, four miles outside the valley, her heart was set racing when she arrived at the cabin of Rocky Mountain Jim, a trapper notorious for his booze-addled rages and morose isolation. She was intrigued to find that Nugent was far from the desperado of repute. In fact, he was well educated, polite and “strikingly handsome,” she noted immediately, with steely eyes, a “handsome aquiline nose...a very handsome mouth” and flowing golden hair—a man whose features would have been “modelled in marble,” she wrote, had one half of his face not been scarred by a recent grizzly attack, in which he had lost an eye. To her, this contradictory figure was the ultimate Western man, a rugged child of nature who also wrote poetry and could declaim in Greek and Latin.

**********

Today, the Colorado Rockies are more than ever associated with health, wellness and the pleasures of the outdoors. Millions of American travelers unconsciously follow in the footsteps of the Gilded Age pioneers every year, and the locals, far from brawling in sawdust-floored saloons, have eagerly joined the adventurers’ ranks. In summer, it feels as if the entire state is in perpetual motion, climbing, rafting, biking or fly fishing.

“Colorado has come full circle,” says Kyle Patterson, information officer at Rocky Mountain National Park, which is celebrating its centenary in 2015. “Our hiking trails follow the same routes used by those early travelers. Americans still come here to escape the cities and breathe pure air. And the landscape hasn’t changed. Look at the mountain skyline as you drive into the national park—it’s like a Gilded Age oil painting.”

Many of the Victorian resort hotels on the Rocky Mountain health circuit also survive intact. A traveler can still stay in the ornate Strater Hotel in Durango, where Louis L’Amour wrote a string of western novels, take high tea at the Hotel Boulderado in Boulder, whose canopied atrium of stained glass evokes an American cathedral, or step from the turreted Cliff House in Manitou Springs to sip from springs first tapped in the 19th century. The thermal pools of Glenwood Springs are still overlooked by the Hotel Colorado, modeled on the Villa Medici in Rome. The town had changed its name from Defiance to sound less lawless, and in 1893, the hotel even imported sophisticated desk staff from London and chambermaids from Boston. The local Avalanche newspaper cheekily claimed that the “Boston Beauties” had come West to look for husbands, a suggestion they violently rejected in an open letter, saying they had no interest in “much abused, rheumatic cowboys and miners,” and would prefer to find spouses among refined Eastern guests.

These days, of course, Coloradans can hold their own on the refinement stakes. In Boulder, a town that has out-Portlanded Portland in hipster culture, some abandoned mine shafts are used for storing craft beers. Vineyards have sprouted on land that once hosted cattle ranches, while wineries with names like Infinite Monkey Theorem sell boutique Colorado wines. And a liberal take on the tradition of “health tourism” is the state’s pioneering stand on legalized marijuana, with dispensaries marked with green crosses and signs offering “Health” and “Wellness.”

But to me, as a traveler weaned on the dramatic and unpredictable sagas of the past, Colorado’s comfortable new era created an imaginative barrier: On several casual visits, I found that the state had become just a little too civilized. It was deflating to find, for example, that the Telluride bank containing the safe robbed in 1889 by Butch Cassidy was now a sunglass shop. And so, last summer, I decided to try a more active approach. I would immerse myself in the Gilded Age West by tracking down the Rocky Mountain trails of intrepid adventurers such as Isabella Bird. Somewhere beyond the organic brewpubs, I hoped, Colorado’s antique sense of excitement could still be found.

**********

Like other “parks,” or high valleys, in the Rockies, Estes Park is an open, grassy expanse, lined by forest, creating a naturally enclosed cattle pasture, as if purposely designed for ranchers. “No words can describe our surprise, wonder and joy at beholding such an unexpected sight,” remarked Milton Estes, the son of the first settler to stumble upon it, in 1859. “We had a little world all to ourselves.” Today, as the gateway to Rocky Mountain National Park, Estes Park is flushed with three million road-trippers a year, and it takes serious legwork to escape the clogged streets and Western boot stores. (To alleviate the overcrowding, park officials are now considering closing off certain areas on the park’s busiest days.) I contacted the resident historian, James Pickering, who has written or edited 30 books on Colorado history and the West, to help me reconstruct the town of 140 years ago.

“This is actually the same horse track travelers used in the 1870s,” Pickering shouted, as he directed me away from busy Highway 36 to the east of Estes Park, dodged a barbed wire fence and plunged into waist-high grass. A few steps away from the modern road and we were on a quiet trail lined by aspen and lodgepole pine, and thick with wildflowers. Below us stretched the lush meadow framed by a rugged skyline of snowcapped granite mountains, with the 14,259-foot-high Longs Peak rising smoothly at their heart, a scene resembling the cover of a box of Swiss chocolates.

“You see, it really does look like the Switzerland of America,” Pickering said with a laugh.

The jovial, silver-haired Pickering has edited an anthology of writings about the national park for its 100th anniversary. It was Samuel Bowles, the editor of the influential Springfield Republican newspaper in Massachusetts, who first compared Colorado to Europe. “Bowles was really just looking for a metaphor Easterners would understand,” Pickering explained. “It provided a point of reference. And I guess Americans have always been braggarts: ‘Our mountains are as good as yours.’”

Back in the car, Pickering produced some Gilded Age stereoscopic photos, and took me to the spots where they were taken. Many buildings have vanished (the charred remains of a luxury hotel built by Lord Dunraven in 1877, for example, would have been across the street from what is now the local golf course), but the scenery was easily recognizable. “Nature really blessed Estes Park,” he mused. “Our mountains contain few minerals, so they weren’t stripped bare by miners, and our winters are very mild, so they aren’t scarred by ski runs.”

Finally, we paused by Muggins Gulch, on a now-private subdivision, the site of the cabin where Rocky Mountain Jim and Isabella Bird met in 1873. “She was totally entranced by Jim Nugent,” Pickering said. “His charm and chivalry were utterly at odds with the stereotype of the mountain man. But it’s an open question how far the romance went.” The renegade Jim, by the same token, seemed fascinated with Isabella, despite her “puffin-like” appearance. He made daily visits to her cabin, amusing other settlers as he took her on wilderness excursions, most famously climbing Longs Peak, where he dragged her up “like a bale of goods.” By the fireside, he sang Irish ballads and reminisced about his misspent youth—spinning a Boy’s Own saga, Isabella wrote, of running away from home after a doomed love affair in Quebec, and working as an Indian scout and a trapper with Hudson’s Bay Company, the whole time losing himself in whiskey. “My soul dissolved in pity for his dark, lost, self-ruined life,” wrote Isabella, who had campaigned against alcohol abuse for years.

The romantic tension exploded a few weeks later, on a ride past the beaver dams of Fall River, when Jim passionately declared (Isabella wrote to her sister) that “he was attached to me and it was killing him....I was terrified. It made me shake all over and nearly cry.” Attracted though she was, a proper lady could not allow the attentions of such a reprobate as Jim to continue, and as they sat beneath a tree together for two hours, she sadly explained that a romantic future together was impossible, especially because of his reckless drinking. (“‘Too late! too late!’ he always answered. ‘For such a change.’”)

Her final verdict to her sister was that Jim was just too wild—“a man whom any woman might love but who no sane woman would marry.”

**********

The Rockies may appear genteel from a distance, but climbing them carries risks, and I had to admire Isabella’s pluck. In order to tackle Longs Peak, as she and Jim had done, park rangers told me, I would have to start at 1 a.m. to avoid summer lightning storms, which had just killed two hikers that July. Even less ambitious trails required caution. As I crossed the tundra above the tree line to watch a herd of elk, the weather took a sudden turn for the worse, as it very often does, and my hair began literally standing on end, drawn by static electricity. Looking up at the thunder clouds, I realized I was becoming a human conductor. (The best defense in a storm is unnervingly called the “lightning desperation position,” a ranger explained. “Put your feet together, squat down on the balls of your feet, close your eyes and cover your ears, and stay there for 30 minutes.” Lightning can strike long after clouds have passed, a little-known fact that can be fatal.) Instead of being electrocuted, I was caught in a sudden hailstorm, in which lumps of ice pounded my neck and arms into a frozen rash. But just like 140 years ago, the discomforts dissolved when gazing down at the granite peaks stretching to the horizon—a vision that recalls Lord Byron’s view of the Alps, where mountains shone “like truth” and ice evoked “a frozen hurricane.”

Gilded Age travelers were most at home on horseback, so I decided to explore the forests as they did. The question was, where was I going to find a “mountain man” as a guide in Colorado these days? I asked around the climbing stores and bars of Estes Park before discovering there was, in fact, one last equivalent, named Tim Resch—Rocky Mountain Tim, you could say—who I was told lived with his horses “off the grid.”

We met up on an empty stretch of Fish Creek Road just after dawn. Like Nugent, Resch was not exactly a laconic Western hermit. Wearing the regulation ten-gallon hat and leather vest, and sporting a silver mustache, he delivered a steady mix of wilderness survival tips and deadpan jokes as he revved his ATV up a steep rock-strewn road, then through a cattle postern in the middle of nowhere. (“I live in a gated community,” he explained.) His is the only cabin surrounded by thousands of acres of Roosevelt National Forest, and for the next three hours, we rode along paths used by 19th-century fur trappers and Victorian sightseers alike. “I’m the only one who uses these old trails anymore,” he lamented, as we ducked beneath pine branches. “You can really imagine what it was like 100 years ago. It’s a little slice of heaven.”

Resch’s life story even sounds like an update of Rocky Mountain Jim’s. Most of his family was killed in a car crash when he was 13. Not long after, he saw Jeremiah Johnson, the movie about a 19th-century Western loner starring Robert Redford. “I decided right then and there, that’s what I want to do, live in the mountains and be by myself.” He achieved the dream 27 years ago as a wilderness guide for hunters and riders. (Resch even observed that he resembled Jim in that “no sane woman” would marry him. He spoke wryly about the two wives who had left him: “I prefer the catch-and-release program now.”)

Our trail passed the remains of farmhouses from the 1890s and the early 20th century, long abandoned. The Boren Homestead, now little more than its foundation, caught fire in 1914, housed a hotel in the 1920s and during Prohibition became one of America’s most isolated illegal bars. (“If that bed could talk,” Resch remarked as we passed a rusting mattress frame.) Although the cabins are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, nothing is actively done by the Forest Service to stem their slow disintegration. “They’re just going to be gone in a few years,” Resch murmured. “We’re pretty lucky to be able to see them at all.”

**********

It is not just the empty countryside that can feel haunted. In Estes Park, I was staying in the Stanley Hotel, a rambling, creaking wooden palace where Stephen King was inspired to write The Shining. The TVs in every room run the Stanley Kubrick film on perpetual loop. The exteriors were shot in Oregon, and now paranormal tours are offered nightly. The hotel even employs a resident psychic with her own private office.

Victorians also had a fondness for the occult, with séances being a major fad. Isabella and Jim spent many intense hours discussing spiritualism before their final parting. In December 1873, after escorting her to the rail lines for her journey east, Jim said with emotion: “I may not see you again in this life, but I shall when I die.” Seven months later, Isabella learned that Jim had been shot by another settler in Estes Park in an obscure dispute, and was seriously wounded. That September, she was in a hotel in Switzerland—the Switzerland of Europe, that is—when she had a vision of Jim visiting her. “I have come, as I promised,” she reported the apparition saying, in a letter. “Then he waved his hands toward me, and said, ‘Farewell.’” Later, Isabella contacted spiritualists at Cambridge University to investigate the vision. Corresponding with newspapers and eyewitnesses in Colorado, the experts concluded that she had been visited by Jim on the very same day he died, although not exactly at the same hour.

Isabella was devastated, but she was also a writer. Her memoir on Colorado appeared in 1879 to popular acclaim, largely because of Jim’s exotic presence, which she played up for melodrama. “Nobody has been able to prove whether anything she wrote about Jim’s past was really true,” says Pickering. “She made him into a one-dimensional stereotype, as if he had stepped out of a dime western. In a way, she prostituted the guy, and turned him into something he wasn’t.” Whatever the literary ethics, Bird had a best seller on her hands, and Estes Park has never looked back as a world-renowned destination.

**********

By the 1890s, travelers stopped looking for echoes of Europe in the West, and started enjoying the landscape on its own terms. Inspired by works such as Bird’s, along with those of John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, camping and the outdoor life began to take off with the broader American public. As travel became more democratic, a push for conservation led to the creation of the Rocky Mountain National Park, America’s tenth, in 1915, supported by Enos Mills, a wiry, irascible figure who first came to Colorado after a digestive illness and ended up a preternaturally fit mountain guide, climbing Longs Peak more than 300 times.

The dangers of the frontier were also gradually becoming a thing of the past. Even hard-bitten mining towns, which supplied the gilt for America’s Gilded Age, began to take on a romantic air. The process is taking creative new twists today. Above Boulder, a railway built to carry ore in 1883 has recently been torn up and reborn as a mountain bike trail. The aptly named “Switzerland Trail” now zigzags for 14 miles along sheer cliffs and past streams littered with rusting tools. Sites such as Wallstreet remain in poetic decay, but Colorado’s schedule of spring floods, summer fires and winter blizzards continues to punish wooden structures mercilessly, and they are likely to go the way of the homesteads in the Roosevelt National Forest. “It’s sad to look at old photos,” said my biking guide, Justin Burger. “We’re really seeing the tail end of mining history here.”

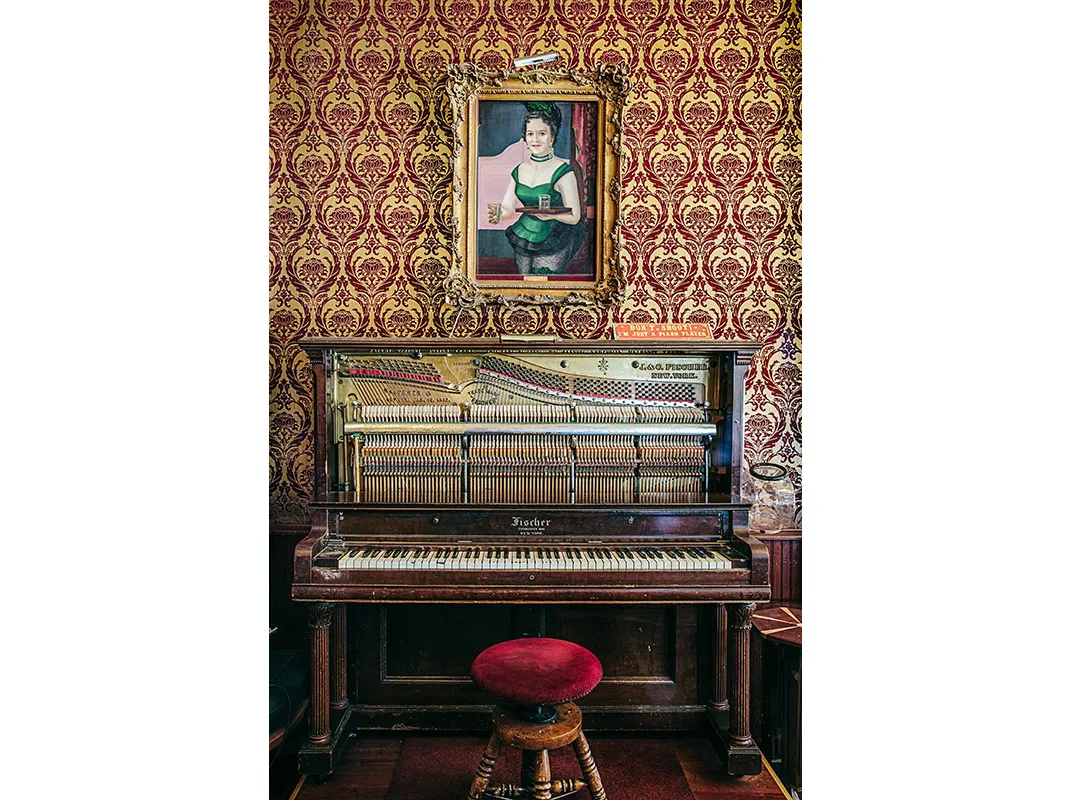

But not all of Colorado’s past is fading. To find a more optimistic conservation story, I made the pilgrimage to Dunton Hot Springs, a mining ghost town that has been painstakingly converted into the West’s most original historic resort. Lost in the pine-clad San Juan Mountains, 22 miles along a red-dirt road, Dunton was thriving in 1905 with a population as high as 300, only to be abandoned 13 years later when the gold petered out. The ghost town was reoccupied for a while by hippies in

the 1970s—“the naked volleyball games are fondly remembered,” one Durango resident told me—and then biker gangs, who covered cabins with graffiti and shot holes in their tin roofs.

A decade ago, after a seven-year restoration by new owners—Christoph Henkel, a billionaire business executive, and his wife, Katrin Bellinger, both art dealers from Munich—the entire site was resurrected as a lodge. Dunton now encapsulates Colorado’s historic extremes, combining a rugged frontier setting with Gilded Age-level comforts. The hot springs are housed within a rustic-chic “bathhouse” crafted from tree trunks and glass, and the original copper bathtub salvaged from the bordello is still in one guest cabin. An ambitious library filled with art books offers a bottle of whiskey so readers can indulge, Rocky Mountain Jim-like, while pondering classical art books and, perhaps, declaiming in Latin and Greek. (It’s an homage to the discovery of an early 20th-century crate of Dickel under the floorboards.)

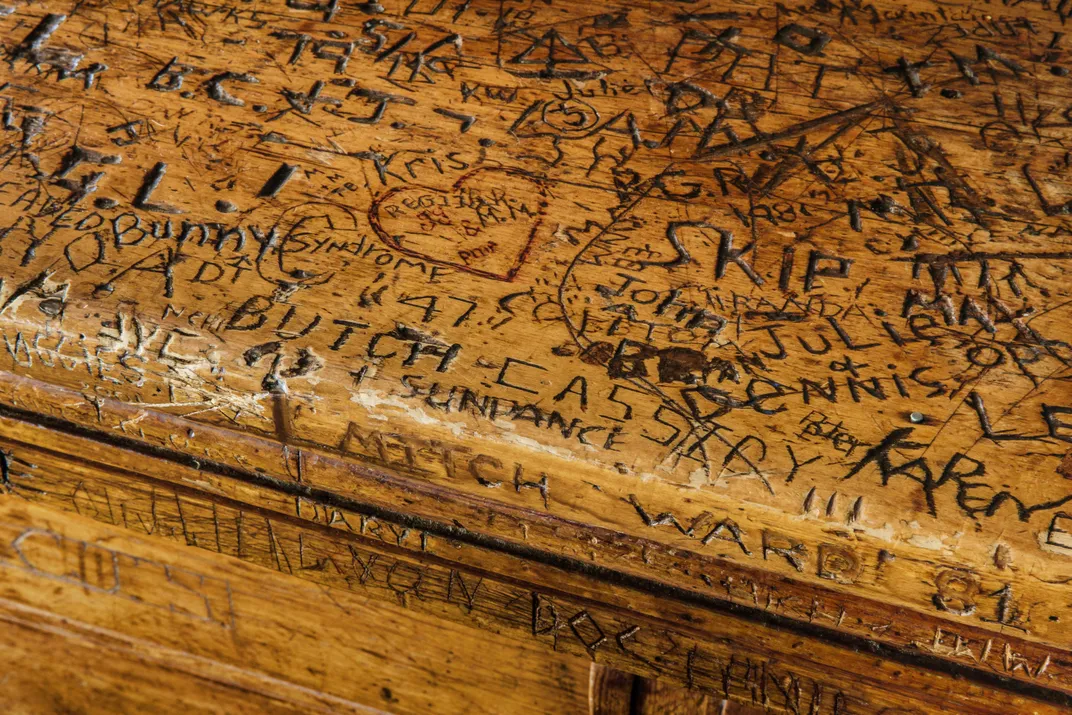

Adjacent to the town’s original dance hall, the ancient wooden bar in the saloon is dense with graffiti, including, prominently, the names “Butch Cassidy” and “Sundance.”

“That’s the most photographed few inches in Dunton,” the barman remarked.

I asked if there was any chance that it was actually real.

“Well, this part of Colorado was definitely their stomping ground in the 1890s, and we’re pretty sure they hid out in Dunton. So it’s not impossible...”

Then again, I suggested, the graffiti might only date back to the 1969 film starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, and some creative hippies with a penknife.

“But hell, this is the West,” shrugged one of the local drinkers propping up the bar. “Nobody can prove it’s not true. A good story is what counts in the end.”

Isabella Bird might, with a lovelorn sigh, have agreed.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story mentioned an incorrect title for James Pickering's anthology and an erroneous location for the remains of a luxury hotel in Estes Park. It also wrongly attributed a quote by Milton Estes to his father, Joel.

Related Reads

America's Switzerland

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)