Children of the Vietnam War

Born overseas to Vietnamese mothers and U.S. servicemen, Amerasians brought hard-won resilience to their lives in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Vietnamese-Amerasians-celebrate-their-heritage-631.jpg)

They grew up as the leftovers of an unpopular war, straddling two worlds but belonging to neither. Most never knew their fathers. Many were abandoned by their mothers at the gates of orphanages. Some were discarded in garbage cans. Schoolmates taunted and pummeled them and mocked the features that gave them the face of the enemy—round blue eyes and light skin, or dark skin and tight curly hair if their soldier-dads were African-Americans. Their destiny was to become waifs and beggars, living in the streets and parks of South Vietnam's cities, sustained by a single dream: to get to America and find their fathers.

But neither America nor Vietnam wanted the kids known as Amerasians and commonly dismissed by the Vietnamese as "children of the dust"—as insignificant as a speck to be brushed aside. "The care and welfare of these unfortunate children...has never been and is not now considered an area of government responsibility," the U.S. Defense Department said in a 1970 statement. "Our society does not need these bad elements," the Vietnamese director of social welfare in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) said a decade later. As adults, some Amerasians would say that they felt cursed from the start. When, in early April 1975, Saigon was falling to Communist troops from the north and rumors spread that southerners associated with the United States might be massacred, President Gerald Ford announced plans to evacuate 2,000 orphans, many of them Amerasians. Operation Babylift's first official flight crashed in the rice paddies outside Saigon, killing 144 people, most of them children. South Vietnamese soldiers and civilians gathered at the site, some to help, others to loot the dead. Despite the crash, the evacuation program continued another three weeks.

"I remember that flight, the one that crashed," says Nguyen Thi Phuong Thuy. "I was about 6, and I'd been playing in the trash near the orphanage. I remember holding the nun's hand and crying when we heard. It was like we were all born under a dark star." She paused to dab at her eyes with tissue. Thuy, whom I met on a trip to Vietnam in March 2008, said she had never tried to locate her parents because she had no idea where to start. She recalls her adoptive Vietnamese parents arguing about her, the husband shouting, "Why did you have to get an Amerasian?" She was soon sent off to live with another family.

Thuy seemed pleased to find someone interested in her travails. Over coffee and Cokes in a hotel lobby, she spoke in a soft, flat voice about the "half-breed dog" taunts she heard from neighbors, of being denied a ration card for food, of sneaking out of her village before others rose at sunrise to sit alone on the beach for hours and about taking sleeping pills at night to forget the day. Her hair was long and black, her face angular and attractive. She wore jeans and a T-shirt. She looked as American as anyone I might have passed in the streets of Des Moines or Denver. Like most Amerasians still in Vietnam, she was uneducated and unskilled. In 1992 she met another Amerasian orphan, Nguyen Anh Tuan, who said to her, "We don't have a parent's love. We are farmers and poor. We should take care of each other." They married and had two daughters and a son, now 11, whom Thuy imagines as the very image of the American father she has never seen. "What would he say today if he knew he had a daughter and now a grandson waiting for him in Vietnam?" she asked.

No one knows how many Amerasians were born—and ultimately left behind in Vietnam—during the decade-long war that ended in 1975. In Vietnam's conservative society, where premarital chastity is traditionally observed and ethnic homogeneity embraced, many births of children resulting from liaisons with foreigners went unregistered. According to the Amerasian Independent Voice of America and the Amerasian Fellowship Association, advocacy groups recently formed in the United States, no more than a few hundred Amerasians remain in Vietnam; the groups would like to bring all of them to the United States. The others—some 26,000 men and women now in their 30s and 40s, together with 75,000 Vietnamese they claimed as relatives—began to be resettled in the United States after Representative Stewart B. McKinney of Connecticut called their abandonment a "national embarrassment" in 1980 and urged fellow Americans to take responsibility for them.

But no more than 3 percent found their fathers in their adoptive homeland. Good jobs were scarce. Some Amerasians were vulnerable to drugs, became gang members and ended up in jail. As many as half remained illiterate or semi-illiterate in both Vietnamese and English and never became U.S. citizens. The mainstream Vietnamese-American population looked down on them, assuming that their mothers were prostitutes—which was sometimes the case, though many of the children were products of longer-term, loving relationships, including marriages. Mention Amerasians and people would roll their eyes and recite an old saying in Vietnam: Children without a father are like a home without a roof.

The massacres that President Ford had feared never took place, but the Communists who came south after 1975 to govern a reunited Vietnam were hardly benevolent rulers. Many orphanages were closed, and Amerasians and other youngsters were sent off to rural work farms and re-education camps. The Communists confiscated wealth and property and razed many of the homes of those who had supported the American-backed government of South Vietnam. Mothers of Amerasian children destroyed or hid photographs, letters and official papers that offered evidence of their American connections. "My mother burned everything," says William Tran, now a 38-year-old computer engineer in Illinois. "She said, ‘I can't have a son named William with the Viet Cong around.' It was as though your whole identity was swept away." Tran came to the United States in 1990 after his mother remarried and his stepfather threw him out of the house.

Hoi Trinh was still a schoolboy in the turbulent postwar years when he and his schoolteacher parents, both Vietnamese, were uprooted in Saigon and, joining an exodus of two million southerners, were forced into one of the "new economic zones" to be farmers. He remembers taunting Amerasians. Why? "It didn't occur to me then how cruel it was. It was really a matter of following the crowd, of copying how society as a whole viewed them. They looked so different than us.... They weren't from a family. They were poor. They mostly lived on the street and didn't go to school like us."

I asked Trinh how Amerasians had responded to being confronted in those days. "From what I remember," he said, "they would just look down and walk away."

Trinh eventually left Vietnam with his family, went to Australia and became a lawyer. When I first met him, in 1998, he was 28 and working out of his bedroom in a cramped Manila apartment he shared with 16 impoverished Amerasians and other Vietnamese refugees. He was representing, pro bono, 200 or so Amerasians and their family members scattered through the Philippines, negotiating their futures with the U.S. Embassy in Manila. For a decade, the Philippines had been a sort of halfway house where Amerasians could spend six months, learning English and preparing for their new lives in the United States. But U.S. officials had revoked the visas of these 200 for a variety of reasons—fighting, excessive use of alcohol, medical problems, "anti-social" behavior. Vietnam would not take them back and the Manila government maintained that the Philippines was only a transit center. They lived in a stateless twilight zone. But over the course of five years, Trinh managed to get most of the Amerasians and scores of Vietnamese boat people trapped in the Philippines resettled in the United States, Australia, Canada and Norway.

When one of the Amerasians in a Philippine refugee camp committed suicide, Trinh adopted the man's 4-year-old son and helped him become an Australian citizen. "It wasn't until I went to the Philippines that I learned of the Amerasians' issues and ordeals in Vietnam," Trinh told me. "I've always believed that what you sow is what you get. If we are treated fairly and with tenderness, we will grow up being exactly like that. If we are wronged and discriminated against and abused in our childhood, like some of the Amerasians were, chances are we will grow up not being able to think, rationalize or function like other ‘normal' people."

After being defeated at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and forced to withdraw from Vietnam after nearly a century of colonial rule, France quickly evacuated 25,000 Vietnamese children of French parentage and gave them citizenship. For Amerasians the journey to a new life would be much tougher. About 500 of them left for the United States with Hanoi's approval in 1982 and 1983, but Hanoi and Washington—which did not then have diplomatic relations—could not agree on what to do with the vast majority who remained in Vietnam. Hanoi insisted they were American citizens who were not discriminated against and thus could not be classified as political refugees. Washington, like Hanoi, wanted to use the Amerasians as leverage for settling larger issues between the two countries. Not until 1986, in secret negotiations covering a range of disagreements, did Washington and Hanoi hold direct talks on Amerasians' future.

But by then the lives of an American photographer, a New York congressman, a group of high-school students in Long Island and a 14-year-old Amerasian boy named Le Van Minh had unexpectedly intertwined to change the course of history.

In October 1985, Newsday photographer Audrey Tiernan, age 30, on assignment in Ho Chi Minh City, felt a tug on her pant leg. "I thought it was a dog or a cat," she recalled. "I looked down and there was Minh. It broke my heart." Minh, with long lashes, hazel eyes, a few freckles and a handsome Caucasian face, moved like a crab on all four limbs, likely the result of polio. Minh's mother had thrown him out of the house at the age of 10, and at the end of each day his friend, Thi, would carry the stricken boy on his back to an alleyway where they slept. On that day in 1985, Minh looked up at Tiernan with a hint of a wistful smile and held out a flower he had fashioned from the aluminum wrapper in a pack of cigarettes. The photograph Tiernan snapped of him was printed in newspapers around the world.

The next year, four students from Huntington High School in Long Island saw the picture and decided to do something. They collected 27,000 signatures on a petition to bring Minh to the United States for medical attention.They asked Tiernan and their congressman, Robert Mrazek, for help.

"Funny, isn't it, how something that changed so many lives emanated from the idealism of some high-school kids," says Mrazek, who left Congress in 1992 and now writes historical fiction and nonfiction. Mrazek recalls telling the students that getting Minh to the United States was unlikely. Vietnam and the United States were enemies and had no official contacts; at this low point, immigration had completely stopped. Humanitarian considerations carried no weight. "I went back to Washington feeling very guilty," he says. "The students had come to see me thinking their congressman could change the world and I, in effect, had told them I couldn't." But, he asked himself, would it be possible to find someone at the U.S. State Department and someone from Vietnam's delegation to the United Nations willing to make an exception? Mrazek began making phone calls and writing letters.

Several months later, in May 1987, he flew to Ho Chi Minh City. Mrazek had found a senior Vietnamese official who thought that helping Minh might lead to improved relations with the United States, and the congressman had persuaded a majority of his colleagues in the House of Representatives to press for help with Minh's visa. He could bring the boy home with him. Mrazek had hardly set his feet on Vietnamese soil before the kids were tagging along. They were Amerasians. Some called him "Daddy." They tugged at his hand to direct him to the shuttered church where they lived. Another 60 or 70 Amerasians were camped in the yard. The refrain Mrazek kept hearing was, "I want to go to the land of my father."

"It just hit me," Mrazek says. "We weren't talking about just the one boy. There were lots of these kids, and they were painful reminders to the Vietnamese of the war and all it had cost them. I thought, ‘Well, we're bringing one back. Let's bring them all back, at least the ones who want to come.' "

Two hundred Huntington High students were on hand to greet Minh, Mrazek and Tiernan when their plane landed at New York's Kennedy International Airport.

Mrazek had arranged for two of his Centerport, New York, neighbors, Gene and Nancy Kinney, to be Minh's foster parents. They took him to orthopedists and neurologists, but his muscles were so atrophied "there was almost nothing left in his legs," Nancy says. When Minh was 16, the Kinneys took him to see the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., pushing him in his new wheelchair and pausing so the boy could study the black granite wall. Minh wondered if his father was among the 58,000 names engraved on it.

"Minh stayed with us for 14 months and eventually ended up in San Jose, California," says Nancy, a physical therapist. "We had a lot of trouble raising him. He was very resistant to school and had no desire to get up in the morning. He wanted dinner at midnight because that's when he'd eaten on the streets in Vietnam." In time, Minh calmed down and settled into a normal routine. "I just grew up," he recalled. Minh, now 37 and a newspaper distributor, still talks regularly on the phone with the Kinneys. He calls them Mom and Dad.

Mrazek, meanwhile, turned his attention to gaining passage of the Amerasian Homecoming Act, which he had authored and sponsored. In the end, he sidestepped normal Congressional procedures and slipped his three-page immigration bill into a 1,194-page appropriations bill, which Congress quickly approved and President Ronald Reagan signed in December 1987. The new law called for bringing Amerasians to the United States as immigrants, not refugees, and granted entry to almost anyone who had the slightest touch of a Western appearance. The Amerasians who had been so despised in Vietnam had a passport—their faces—to a new life, and because they could bring family members with them, they were showered with gifts, money and attention by Vietnamese seeking free passage to America. With the stroke of a pen, the children of dust had become the children of gold.

"It was wild," says Tyler Chau Pritchard, 40, who lives in Rochester, Minnesota, and was part of a 1991 Amerasian emigration from Vietnam. "Suddenly everyone in Vietnam loved us. It was like we were walking on clouds. We were their meal ticket, and people offered a lot of money to Amerasians willing to claim them as mothers and grandparents and siblings."

Counterfeit marriage licenses and birth certificates began appearing on the black market. Bribes for officials who would substitute photographs and otherwise alter documents for "families" applying to leave rippled through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Once the "families" reached the United States and checked into one of 55 transit centers, from Utica, New York, to Orange County, California, the new immigrants would often abandon their Amerasian benefactors and head off on their own.

It wasn't long before unofficial reports began to detail mental-health problems in the Amerasian community. "We were hearing stories about suicides, deep-rooted depression, an inability to adjust to foster homes," says Fred Bemak, a professor at George Mason University who specializes in refugee mental-health issues and was enlisted by the National Institute for Mental Health to determine what had gone wrong. "We'd never seen anything like this with any refugee group."

Many Amerasians did well in their new land, particularly those who had been raised by their Vietnamese mothers, those who had learned English and those who ended up with loving foster or adoptive parents in the United States. But in a 1991-92 survey of 170 Vietnamese Amerasians nationwide, Bemak found that some 14 percent had attempted suicide; 76 percent wanted, at least occasionally, to return to Vietnam. Most were eager to find their fathers, but only 33 percent knew his name.

"Amerasians had 30 years of trauma, and you can't just turn that around in a short period of time or undo what happened to them in Vietnam," says Sandy Dang, a Vietnamese refugee who came to the United States in 1981 and has run an outreach program for Asian youths in Washington, D.C. "Basically they were unwanted children. In Vietnam, they weren't accepted as Vietnamese and in America they weren't considered Americans. They searched for love but usually didn't find it. Of all the immigrants in the United States, the Amerasians, I think, are the group that's had the hardest time finding the American Dream."

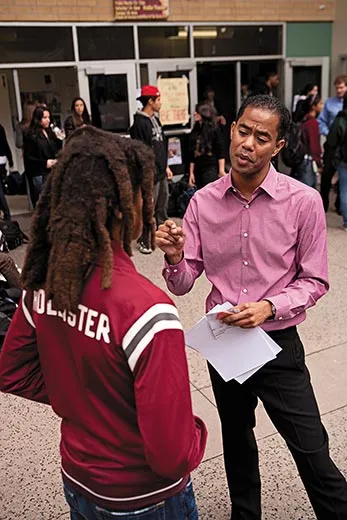

But Amerasians are also survivors, their character steeled by hard times, and not only have they toughed it out in Vietnam and the United States, they are slowly carving a cultural identity, based on the pride—not the humiliation—of being Amerasian. The dark shadows of the past are receding, even in Vietnam, where discrimination against Amerasians has faded. They're learning how to use the American political system to their advantage and have lobbied Congress for passage of a bill that would grant citizenship to all Amerasians in the United States. And under the auspices of groups like the Amerasian Fellowship Association, they are holding regional "galas" around the country—sit-down dinners with music and speeches and hosts in tuxedos—that attract 500 or 600 "brothers and sisters" and celebrate the Amerasian community as a unique immigrant population.

Jimmy Miller, a quality inspector for Triumph Composite Systems Inc., a Spokane, Washington, company making parts for Boeing jets, considers himself one of the fortunate ones. His grandmother in Vung Tau took him in while his mother served a five-year sentence in a re-education camp for trying to flee Vietnam. He says his grandmother filled him with love and hired an "underground" teacher to tutor him in English. "If she hadn't done that, I'd be illiterate," Miller says. At age 22, in 1990, he came to the United States with a third-grade education and passed the GED to earn a high-school diploma. It was easy convincing the U.S. consular officer who interviewed him in Ho Chi Minh City that he was the son of an American. He had a picture of his father, Sgt. Maj. James A. Miller II, exchanging wedding vows with Jimmy's mother, Kim, who was pregnant with him at the time. He carries the picture in his wallet to this day.

Jimmy's father, James, retired from the U.S. Army in 1977 after a 30-year career. In 1994, he was sitting with his wife, Nancy, on a backyard swing at their North Carolina home, mourning the loss of his son from a previous marriage, James III, who had died of AIDS a few months earlier, when the telephone rang. On the line was Jimmy's sister, Trinh, calling from Spokane, and in typically direct Vietnamese fashion, before even saying hello, she asked, "Are you my brother's father?" "Excuse me?" James replied. She repeated the question, saying she had tracked him down with the help of a letter bearing a Fayetteville postmark he had written Kim years earlier. She gave him Jimmy's telephone number.

James called his son ten minutes later, but mispronounced his Vietnamese name—Nhat Tung—and Jimmy, who had spent four years looking for his father, politely told the caller he had the wrong number and hung up. His father called back. "Your mother's name is Kim, right?" he said. "Your uncle is Marseille? Is your aunt Phuong Dung, the famous singer?" Jimmy said yes to each question. There was a pause as James caught his breath. "Jimmy," he said, "I have something to tell you. I am your dad."

"I can't tell you how tickled I was Jim owned up to his own child," says Nancy. "I have never seen a man happier in my life. He got off the phone and said, "‘My son Jimmy is alive!'" Nancy could well understand the emotions swirling through her husband and new stepson; she had been born in Germany shortly after World War II, the daughter of a U.S. serviceman she never knew and a German mother.

Over the next two years, the Millers crossed the country several times to spend weeks with Jimmy, who, like many Amerasians, had taken his father's name. "These Amerasians are pretty amazing," Nancy said. "They've had to scrap for everything. But you know the only thing that boy ever asked for? It was for unconditional fatherly love. That's all he ever wanted." James Miller died in 1996, age 66, while dancing with Nancy at a Christmas party.

Before flying to San Jose, California, for an Amerasian regional banquet, I called former Representative Bob Mrazek to ask how he viewed the Homecoming Act on its 20th anniversary. He said that there had been times when he had questioned the wisdom of his efforts. He mentioned the instances of fraud, the Amerasians who hadn't adjusted to their new lives, the fathers who had rejected their sons and daughters. "That stuff depressed the hell out of me, knowing that so often our good intentions had been frustrated," he said.

But wait, I said, that's old news. I told him about Jimmy Miller and about Saran Bynum, an Amerasian who is the office manager for actress-singer Queen Latifah and runs her own jewelry business. (Bynum, who lost her New Orleans home in Hurricane Katrina, says, "Life is beautiful. I consider myself blessed to be alive.") I told him about Tiger Woods look-alike Canh Oxelson, who has an undergraduate degree from the University of San Francisco, a master's degree from Harvard and is dean of students at one of Los Angeles' most prestigious preparatory schools, Harvard-Westlake in North Hollywood. And I told him about the Amerasians who got off welfare and are giving voice to the once-forgotten children of a distant war.

"You've made my day," Mrazek said.

The cavernous Chinese restaurant in a San Jose mall where Amerasians gathered for their gala filled quickly. Tickets were $40—and $60 if a guest wanted wine and a "VIP seat" near the stage. Plastic flowers adorned each table and there were golden dragons on the walls. Next to an American flag stood the flag of South Vietnam, a country that has not existed for 34 years. An honor guard of five former South Vietnamese servicemen marched smartly to the front of the room. Le Tho, a former lieutenant who had spent 11 years in a re-education camp, called them to attention as a scratchy recording sounded the national anthems of the United States and South Vietnam. Some in the audience wept when the guest of honor, Tran Ngoc Dung, was introduced. Dung, her husband and six children had arrived in the United States just two weeks earlier, having left Vietnam thanks to the Homecoming Act, which remains in force but receives few applications these days. The Trans were farmers and spoke no English. A rough road lay ahead, but, Dung said, "This is like a dream I've been living for 30 years." A woman approached the stage and pressed several $100 bills into her hand.

I asked some Amerasians if they were expecting Le Van Minh, who lived not far away in a two-bedroom house, to come to the gala. They had never heard of Minh. I called Minh, now a man of 37, with a wife from Vietnam and two children, 12 and 4. Among the relatives he brought to the United States is the mother who threw him out of the house 27 years ago.

Minh uses crutches and a wheelchair to get around his home and a specially equipped 1990 Toyota to crisscross the neighborhoods where he distributes newspapers. He usually rises shortly after midnight and doesn't finish his route until 8 a.m. He says he's too busy for any spare-time activities but hopes to learn how to barbecue one day. He doesn't think much about his past life as a beggar in the streets of Saigon. I asked him if he thought life had given him a fair shake.

"Fair? Oh, absolutely, yes. I'm not angry at anyone," said Minh, a survivor to the core.

David Lamb wrote about Singapore in the September 2007 issue.

Catherine Karnow, born and raised in Hong Kong, has photographed extensively in Vietnam.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article said that Jimmy Miller served in the military for 35 years. He served for 30 years. We apologize for the error.