Chicago Eats

From curried catfish to baba ghanouj, Chicago serves up what may be the finest ethnic cuisine going

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mexican-Pilsen-neighborhood-Chicago-631.jpg)

The people of Chicago, that stormy, husky, brawling kind of town, sure know how to tie on the feed bag. Has any other American city patented so many signature foods? There's deep-dish pizza, smoky Polish sausages, Italian beef sandwiches au jus, and, of course, the classic Chicago-style hot dog: pure Vienna Beef on a warm poppy-seed bun with mustard, relish, pickled peppers, onions, tomato slices, a quartered dill pickle and a dash of celery salt. Alter the formula (or ask for ketchup) and you can head right back to Coney Island, pal. For better or worse, it was Chicago that transformed the Midwest's vast bounty of grains, livestock and dairy foods into Kraft cheese, Cracker Jack and Oscar Mayer wieners. And in recent years, emerging from its role as chuck wagon to the masses, Chicago finally bulled its way into the hallowed precincts of haute cuisine, led by renowned chefs Charlie Trotter, Rick Bayless and Grant Achatz, who's one of the forerunners of a movement known as molecular gastronomy. "They hate the term, but that's how people refer to it," says Mike Sula, a food columnist for the weekly Chicago Reader. "They like to call it 'techno-emotional cuisine.'" But does it taste good? "Oh yeah," he says.

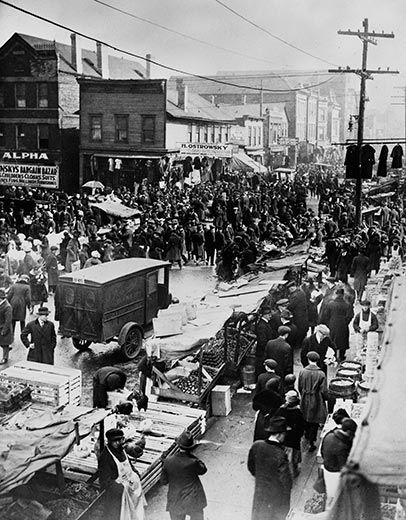

Sula filled me in during a Sunday morning stroll through the historic Maxwell Street Market (now transplanted to Desplaines Street) on the Near West Side. We weren't there for the cutting-edge cuisine, but something much older and more fundamental. Call it street food, peasant food, a taste of home—by any name, Maxwell Street has been serving it up for a long time. So it made sense to include the market on my exploration of what may be the richest of Chicago's culinary treasures: the authentic, old-country eateries scattered throughout the city's ethnic neighborhoods.

In 1951, author Nelson Algren wrote of Chicago streets "where the shadow of the tavern and the shadow of the church form a single dark and double-walled dead end." Yet President Barack Obama's hometown is also a city of hope. Visionaries, reformers, poets and writers, from Theodore Dreiser and Carl Sandburg to Richard Wright, Saul Bellow and Stuart Dybek, have found inspiration here, and Chicago has beckoned to an extraordinary range of peoples—German, Irish, Greek, Swedish, Chinese, Arab, Korean and East African, among many, many others. For each, food is a powerful vessel of shared traditions, a direct pipeline into the soul of a community. Choosing just a few to sample is an exercise in random discovery.

__________________________

Maxwell Street has long occupied a special place in immigrant lore. For decades, the area had a predominantly Jewish flavor; jazzman Benny Goodman, Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, boxing champ and World War II hero Barney Ross, not to mention Oswald assassin Jack Ruby, all grew up nearby. Infomercial king Ron Popeil ("But wait, there's more!") started out hawking gadgets here. African-Americans also figure prominently in the street's history, most memorably through performances by bluesmen like Muddy Waters, Big Bill Broonzy and Junior Wells. Today, the market crackles with Mexican energy—and the alluring aromas of Oaxaca and Aguascalientes. "There's a great range of regional Mexican dishes, mostly antojitos, or little snacks," Sula said. "You get churros, sort of extruded, sugared, fried dough, right out of the oil, fresh—they haven't been sitting around. And champurrado, a thick corn-based, chocolaty drink, perfect for a cold day."

As flea markets go, Maxwell Street is less London's Portobello Road than something out of Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thief, with mounds of used tires, power tools, bootleg videos, baby strollers, tube socks and lug wrenches—a poor man's Wal-Mart. A vendor nicknamed Vincent the Tape Man offers packing materials of every description, from little hockey pucks of electrical tape to jumbo rolls that could double as barbell weights.

Sula and I sampled some huaraches, thin handmade tortillas covered with a potato-chorizo mix, refried beans, grated cotija cheese and mushroomy huitlacoche, also known as corn smut or Mexican truffles—depending on whether you regard this inky fungus as blight or delight. Sula said he was sorry we hadn't been able to find something more transcendent.

"Usually there's a Oaxacan tamale stand where they have the regular corn husk–steamed tamales, plus a flatter, larger version wrapped in a banana leaf—those are fantastic," he said. "Another thing I'm disappointed not to see today is something called machitos, kind of a Mexican haggis. It's sausage, pork or lamb, done in a pig's stomach."

Sula doesn't fool around.

____________________________________________________

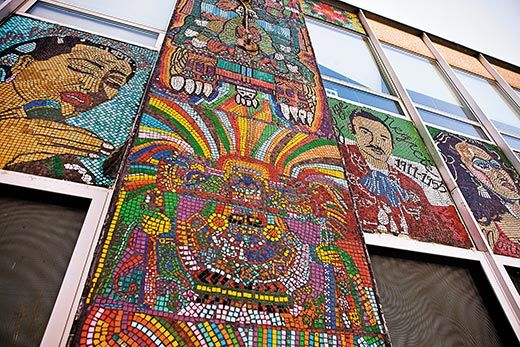

The cultural heart of Chicago's widely dispersed Mexican community is Pilsen, an older neighborhood close to Maxwell Street that was once dominated by Czechs who worked in the city's mills and sweatshops. Many of its solid, artfully embellished buildings look as if they might have been transported brick by brick from old Bohemia, but the area's fiercely colored murals are an unmistakably Mexican declaration of cultural pride and political consciousness.

"Pilsen has a long history of advocacy," said Juana Guzman, vice president of the National Museum of Mexican Art, as we passed the 16th Street Viaduct, the scene of deadly clashes between police and striking railroad workers in 1877. The museum, too, sees itself as activist. "Yes, we're interested in arts programming and artistic displays, but we're also interested in being at the table when there are critical issues impacting our community, such as gentrification," Guzman said. "What brings us all together, of course, is arts and culture—and a big part of that is food."

We drove to La Condesa restaurant, on South Ashland Avenue, not far from the White Sox ballpark. What does it mean to support the White Sox versus the Cubs, I asked. "War!" Guzman shot back, laughing. "Sox fans are blue-collar, Cubs fans are yuppies." And La Condesa was the real deal, she promised. "It's the kind of place where the community and politicians come to meet: people who work in the factories, business people, the alderman. It's more full-service than a lot of places—they have parking, they take credit cards. But they make all their food fresh, and it's well done."

All true, I quickly learned. The tortilla chips were right out of the oven. The guacamole had a creamy, buttery texture. With a dollop of salsa and a few drops of lime, it was a deep experience. Guzman is more of a purist. "To me, nothing is more wonderful than the natural state of a Mexican avocado," she said. "A little salt, and you're in heaven."

As I gorged on green, out came a huge bowl of ceviche—citrus-marinated shrimp in a mildly hot red sauce with fresh cilantro. This was getting serious.

I carved into a juicy slice of cecina estilo guerrero—a marinated skirt steak pounded very thin—and Guzman had pollo en mole negro, chicken covered with mole sauce—a complex, sweet-smoky blend of red ancho chili, chocolate and pureed nuts and spices—all washed down by tall fountain glasses of horchata (rice milk) and agua de jamaica, a cranberry-like iced tea made from the sepals of hibiscus flowers. Buen provecho! Or, as we say another way, bon appétit!

Pop quiz: Which of the following ancient peoples is not only not extinct, but today comprises a worldwide community 3.5 million strong, with around 400,000 in the United States and some 80,000 in the Chicago area?

a) the Hittites

b) the Phoenicians

c) the Assyrians

d) the Babylonians

If you flub this question, take heart from the fact that not one of my well-informed New York City friends correctly answered (c)—the Assyrians, proud descendants of the folks who wrote their grocery lists in cuneiform. After repeated massacres in their native Iraq between the world wars, many members of this Christian minority—who continue to speak a form of Aramaic rooted in biblical times—fled to the United States.

I zeroed in on an Assyrian restaurant, Mataam al-Mataam, in Albany Park, on the North Side. With me were Evelyn Thompson, well-known for her ethnic grocery tours of Chicago, and her equally food-loving husband, Dan Tong, a photographer and former neuroscientist. When we arrived, we learned that Mataam had just relocated and was not yet officially open, but it was filled with men drinking coffee and pulling up chairs to watch an Oscar De La Hoya welterweight bout on a ginormous flat-screen TV. The owner, Kamel Botres, greeted us warmly, told a few stories—he's one of seven brothers who all spell their last name differently—and suggested we dine next-door at his cousin's place, George's Kabab Grill.

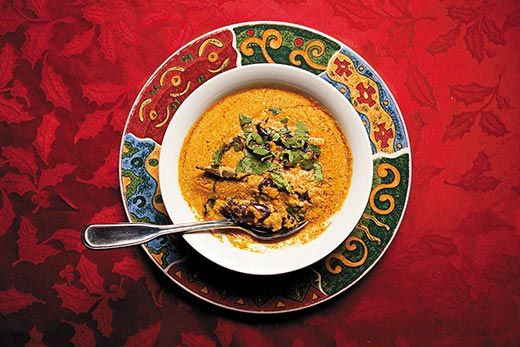

There we feasted on fresh baba ghanouj with black olives and paprika; a plate of torshi, or pickled vegetables; two soups—white lima bean and okra-tomato; charbroiled lamb shish kebab and spiced ground beef kefta kebab sprinkled with (nonpoisonous) sumac, each accompanied by heaps of perfectly done basmati rice served with parsley and lemon—and, best of all, masgouf, a curry-flavored grilled catfish smothered in tomatoes and onions.

Meanwhile, the owner, George Koril, kept busy constructing a fresh ziggurat of shawarma, layering slabs of thinly sliced raw beef onto a vertical spit capped by a ripe tomato. To me it looked like the Tower of Babel.

____________________________________________________

Earlier that evening, Evelyn Thompson had guided me through a fair sampling of the ethnic groceries that are, so to speak, her bread and butter. Nowhere is Chicago's diversity more evident than on West Devon Avenue, which has become the main thoroughfare of the South Asian community. Devon is so well known in India that villagers in remote parts of Gujarat recognize the name.

But it's not all about India and Pakistan. Crammed with restaurants, markets and shops, neon-lit Devon induces a kind of ethnic vertigo. There's La Unica market, founded by Cubans and now sporting Colombian colors; Zapp Thai Restaurant, which used to be a kosher Chinese place; Zabiha, a halal meat market next-door to Hashalom, a Moroccan Jewish restaurant. There's the Devon Market, offering Turkish, Balkan and Bulgarian specialties; pickled Bosnian cabbages; wines from Hungary, Georgia and Germany; and fresh figs, green almonds, pomegranates, persimmons and cactus paddles. And finally, Patel Brothers—flagship of a nationwide chain of 41 Indian groceries, including branches in Mississippi, Utah and Oregon—with 20 varieties of rice, a fresh chutney bar and hundreds of cubbyholes filled with every spice known to humanity. Patel Brothers was the first Indian store on Devon, in 1974, and co-founder Tulsi Patel still patrols the aisles. "He's a very accessible guy, and both he and his brother Mafat have been very active philanthropically," said Colleen Taylor Sen, author of Food Culture in India, who lives nearby.

Colleen and her husband, Ashish, a retired professor and government official, accompanied me to Bhabi's Kitchen, a terrific place just off Devon. "This one has some dishes that you don't find at other Indian restaurants," said Colleen.

"I'm originally from Hyderabad, in the southern part of India," said Bhabi's owner, Qudratullah Syed. "Both northern Indian cuisine and my hometown are represented in here." He's especially proud of his traditional Indian breads—the menu lists 20 varieties made with six different flours. "The sorghum and millet are totally free of gluten, no starch. You might not find these breads, even in India," he said.

Months later, I'm still craving his pistachio naan, made with dried fruits and a dusting of confectioners' sugar.

__________________________

Let's talk about politics and food. Specifically, what are President Obama's favorite Chicago haunts? I had occasion to ask him about this a few years ago, and the first name that popped out was a fine Mexican restaurant, now shuttered, called Chilpancingo. He has also been seen at Rick Bayless' Topolobampo and at Spiaggia, where he celebrates romantic milestones with Michelle. The Obamas are loyal, as well, to the thin-crusted pies at Italian Fiesta Pizzeria in Hyde Park. And the president was a regular at the Valois Cafeteria on 53rd Street. "On the day after the election, they offered free breakfast," said my friend Marcia Lovett, an admissions recruiter for Northern Michigan University, who lives nearby. "The line went all the way around the corner."

And how about soul food, that traditional staple of Chicago's black community? For that, Obama said his favorite was MacArthur's, on the West Side. Still, there are a number of African-American restaurants that can lay some claim to the Obama mantle. Lovett and I headed for one of the best known, Izola's, on the South Side. We were joined by Roderick Hawkins, director of communications for the Chicago Urban League.

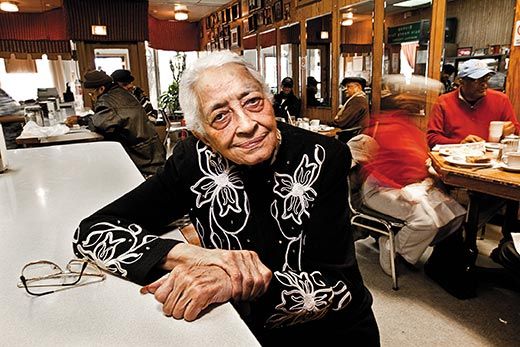

Izola's main dining room confronts you with large blowup photos of former Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, United States Representative Charles Hayes and other local luminaries. Then-Congressman Washington made the decision to run for mayor in 1983 while dining with Hayes at Table 14, said Izola White, who has presided over her restaurant for 52 years. "Harold called me over, he said, 'Come here,'" White recalled. "So I come over and he said, 'Charlie's taking my seat, and I'm gonna run for mayor.' So that was it."

There's a definite clubhouse feel to the place, and a great jukebox never hurts—a compilation CD titled "Izola's Favorites" features Dizzy Gillespie, Alicia Keys and the First Church of Deliverance Choir. Asked what draws him here, Bill Humphrey, a retired policeman, said, "The friendship, the fellowship. It's like a home away from home." And, oh yes, the food. "My favorite is the breakfast—the scrambled eggs with hot links sausage, which you don't get anywhere else," he said. "And I love Izola's smothered pork chops and the short ribs. If you don't see it on the menu, you can order it anyway, 24 hours. Anything, she serves it."

Hawkins gave thumbs up to the stewed chicken and dumplings ("I'm liking it!"), the pork chop ("The seasoning is perfect") and the bread pudding ("It's delicious—very sweet, with a lot of butter"). Lovett voted for the fried chicken ("Not too greasy, just really good") and the greens ("Perfectly balanced, not too sour"). Both my companions have Southern roots, although Hawkins, from Louisiana, isn't nostalgic for everything down-home: "I remember the smell of chitlins cooking in my great-grandmother's kitchen," he said. "It was horrible! I hated it! We would run out of the room."

There's a life-size cutout of Obama on the wall. He has eaten at Izola's several times and has been to White's home, too. "He's a nice young man," White volunteered. "Nice family."

__________________________

I found the Holy Grail—the tastiest food of the trip—when I least expected it. It was at Podhalanka, a quiet restaurant on West Division Street, a thoroughfare known as Polish Broadway—in a city that boasts the largest Polish population outside of Warsaw. Though my own Granny Ottillie was Polish-born and a wonderful cook, I had somehow gotten the impression that Polish cuisine, on the whole, was bland, greasy and heavy. Podhalanka set me straight.

J.R. Nelson lives nearby in Ukrainian Village and works at Myopic Books, a local literary landmark. He's a student of Chicago lore and a friend of my friend Jessica Hopper, a music critic and author who was born in Cole Porter's hometown of Peru, Indiana. J.R., she said, knew a great Polish place, so we all met up there. As we looked over the menu, they told me that the old neighborhood had been losing the grittiness that it had when Nelson Algren prowled the area. "Twenty years ago, it was more rough and tumble," J.R. said in an apologetic tone.

Podhalanka couldn't look plainer—lots of faux brick and linoleum, posters of Pope John Paul II and Princess Diana— and yet, as Jessica told me, "You just look in the window and it's like, obviously, I'm going to eat there."

I won't mention every dish, just the highlights: begin with the soups: shredded cabbage in a tomatoey base; barley with celery, carrots and dill; and miraculous white borscht—delicate, lemony, with thin slices of smoked sausage and pieces of hard-boiled egg somehow coaxed into a silky consistency. (This was $3.20, including the fresh rye bread and butter.) But wait, there's more.

The pièce de résistance was zrazy wieprzowe zawijane—rolled pork stuffed with carrots and celery—which was tender, juicy and subtly peppery. It came with boiled potato, mashed up with a perfect light gravy and topped with fresh dill. The cucumber, cabbage and beet root with horseradish salads were a fine complement, as was rose hips tea.

Helena Madej opened the restaurant in 1981, after arriving from Krakow at age 28. She told us her grandfather first came to Chicago in 1906, but returned to Poland in 1932. Madej's English is grammatically shaky, but perfectly clear.

"Everything is fresh," she said. "We cooking everything. And white borscht, this is recipe my grandma. I'm from big family, because I have four brothers and three sisters. This was hard time, after war, she don't have a lot of money. Just white borscht and bread, and give couple pieces everybody, and we go to school."

She laughed happily at the memory.

Writer Jamie Katz, who reports on arts and culture, lives in New York City. Photographer Brian Smale's home base is Seattle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)