The Adorable and Heroic Animals of the Museum of Maritime Pets

Telling the stories of dogs in sailor hats and cats in life jackets

The human desire for animal companionship thrives on land, but is perhaps even stronger on the high seas. With days, weeks or even months at a time away from civilization, furry friends can offer a respite from the loneliness that often accompanies long voyages. The Museum of Maritime Pets has made it its mission to tell the stories of these loyal friends—dogs, cats, birds, horses and other creatures—through photographs, written records and artifacts. "Our job is to be the clearinghouse, central depository, goodwill ambassador for animals throughout the centuries who have gone or worked at sea,” says Patricia Sullivan, founder and CEO of the museum.

In 2005, Sullivan came up with the idea for the museum when she happened upon the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, and its exhibit “Animals at Sea.” After further searching, she found four other exhibits around the world highlighting animals’ nautical exploits. Noticing something in the zeitgeist—and as a lover of pets herself (she operates a pet-sitting service in Annapolis, Maryland)—Sullivan decided to start a museum of her own.

Sullivan knows a little something about museums, having previously worked at the Rockwood Museum and Gardens in Wilmington, Delaware and the Woodrow Wilson House in Washington, D.C. She also holds a degree in museum studies from George Washington University. With this institutional experience, Sullivan went to work.

Since she didn’t have a physical location, Sullivan turned to the web for researching and collecting, reaching out through social media. “The Internet made these jobs significantly easier,” Sullivan says. “It took what [would] have taken decades of research and condensed it down into a couple of years.”

Besides the museum in Greenwich, Sullivan took advantage of online archives and materials from the National Library of Australia and the Scott Polar Research Institute. She also paid many visits to the research library at the US Naval Institute, located in her hometown of Annapolis. She didn't do all this alone; about 50 volunteers have pledged their time to help collect and archive hundreds of items—artifacts, books, photos and journals—pertaining to stories of animals at sea. The volunteers catalog and archive everything they find and receive, using what Sullivan calls “the old-fashion museum method—manually,” meaning that every item received gets logged into a giant list.

Today, while the museum is essentially a collection of photographs and physical objects with a website, not to mention official 501(c)(3) status, it also occasionally creates physical exhibits, such as "All Paws on Deck," a selection of images of historical maritime pets on view at the Ocean City Life Saving Station Museum through the end of April. The museum also has a research library in Annapolis, available by appointment, and provides historical lectures, off-site programs, partnerships with libraries and educational events—like a recent one at the Chesapeake Children’s Museum.

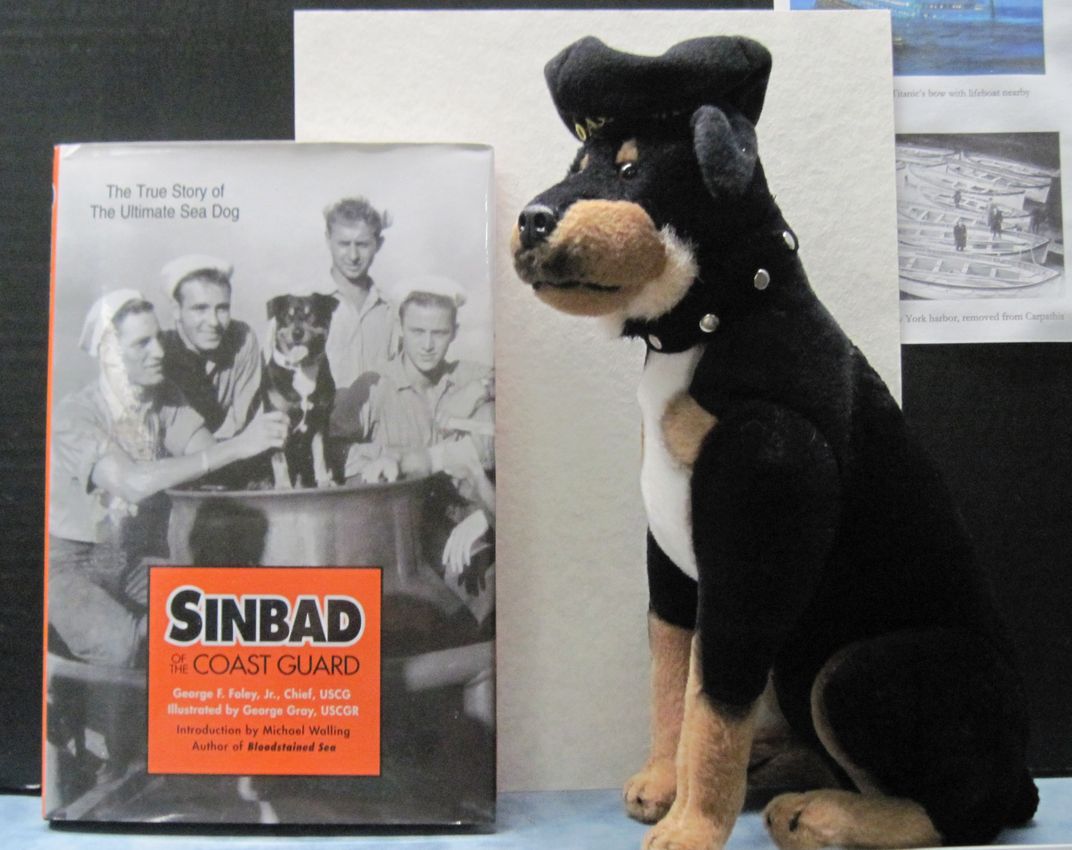

The museum tells many tails (pun intended): There’s Sinbad the Coast Guard dog, adopted by the Coast Guard cutter ship Campbell in 1938, who became such a part of the crew that he was given enlistment forms, a uniform and even his own bunk. “Besides serving as an official mascot, he also caused two international incidents, which luckily did NOT escalate tensions in Greenland or Morocco,” says Sullivan. (The Coast Guard notes that although Sinbad was a “brave and capable sailor,” he occasionally “embarrassed the United States Government by creating disturbances in foreign zones.”) Sinbad became so famous that he was featured in newsreels, was the subject of a Life magazine profile and “wrote” his very own 1944 autobiography, Sinbad of the Coast Guard. An original printing of this book, plus a stuffed Sinbad, are in the collection.

Perhaps the most unique artifact in the museum’s possession is a reproduced tribute written by famed 18th/19th century explorer Matthew Flinders in memory of his beloved cat Trim. Flinders and Trim were the first man-cat team to circumnavigate Australia and endured many a shipwreck together. In the nearly 5,000-word tribute, Flinders lovingly describes his “faithful, intelligent” cat, who nevertheless had a few flaws: “Notwithstanding my great partiality to my friend Trim, strict justice obliges me to cite in this place a trait in his character which by many will be thought a blemish: He was, I am sorry to say it, excessively vain of his person, particularly of his snow-white feet.”

Sullivan’s intention has always been to create a physical museum. Even though she and the museum board are fundraising for a potential space in Annapolis, a permanent location isn’t yet financially viable. Plus, being online has given the Museum of Maritime Pets a flexibility that it wouldn’t have had otherwise. “Having a single location could actually be very limiting and cramp our style,” Sullivan says. “You have to staff it, there’s overhead, and headaches. This way we are free to go with the flow, do what seems to be important at the time."

When the collections are not on display as part of an exhibit, most of the objects are held at a climate-controlled storage facility in Annapolis. A few of the more portable items used in outdoor programs are kept in Sullivan's home. Due to proprietary concerns, the entirety of the collection isn’t available online (redesign discussions are ongoing), but Sullivan emphasizes that for anyone interested in learning more about our furry friends’ lives on the high seas, the information is just a tweet or an email away.

The Museum of Maritime Pets also has its very own ambassador-at-sea, Bailey Boat Cat. Bailey’s home is the SS Nocturne, and he travels the Mediterranean “with two human crew members.” He “blogs” daily, has published a book and is an “advocate” for the Museum of Maritime Pets. While he doesn’t have a permanent land-based home (much like the museum he represents), Bailey shares the same adventurous spirit as every other seafaring animal. Says Sullivan, “He carries on the centuries-old tradition of pets on the high seas.”