A Mega-Dam Dilemma in the Amazon

A huge dam on Peru’s Inambari River will bring much-needed development to the region. But at what cost?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Inambari-Araza-rivers-631.jpg)

The town of Puerto Maldonado lies about 600 miles east of Lima, Peru, but locals call it the Wild West. Gold-buying offices line its main avenues. Bars fill the side streets, offering beer and cheap lomo saltado—stir-fried meat and vegetables served with rice and French fries. Miners and farmers motorbike into the sprawling central market to stock up on T-shirts and dried alpaca meat. Garbage and stray dogs fill the alleyways. There’s a pioneer cemetery on the edge of town, where its first residents are buried.

And Puerto Maldonado is booming. Officially, it has a population of 25,000, but no one can keep up with the new arrivals—hundreds each month, mostly from the Andean highlands. Residents say the town has doubled in size over the past decade. There are only a few paved roads, but asphalt crews are laying down new ones every day. Two- and three-story buildings are going up on every block.

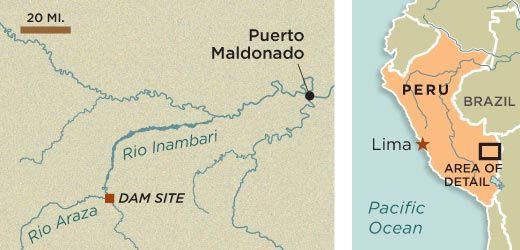

Puerto Maldonado is the capital of Peru’s Madre de Dios region (similar to an American state), which abuts Bolivia and Brazil. The area is almost all rain forest and until recent decades was one of South America’s least populated and most inaccessible areas. But today it is a critical part of Latin America’s economic revolution. Poverty rates are dropping, consumer demand is rising and infrastructure development is on a tear. One of the biggest projects, the $2 billion Inter-oceanic Highway, is nearly complete—and runs straight through Puerto Maldonado. Once open, the highway is expected to see 400 trucks a day carrying goods from Brazil to Peruvian ports.

Later this year a consortium of Brazilian construction and energy companies plans to start building a $4 billion hydroelectric dam on the Inambari River, which starts in the Andes and empties into the Madre de Dios River near Puerto Maldonado. When the dam is completed, in four to five years, its 2,000 megawatts of installed capacity—a touch below that of the Hoover Dam—will make it the largest hydroelectric facility in Peru and the fifth-largest in all of South America.

The Inambari dam, pending environmental impact studies, will be built under an agreement signed last summer in Manaus, Brazil, by Peruvian President Alan García and Brazil’s then-president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. In a joint statement released afterward, the pair praised the deal as “an instrument of great strategic interest to both countries.” At first, most of the dam’s electricity will go to Brazil, which desperately needs power to feed its economic expansion—a projected 7.6 percent in 2011, the fastest in nearly two decades. Over 30 years, the bulk of the electricity will gradually go to Peru to meet its own growing power demands. “The reality is, every year we need more and more energy,” says Antonio Brack Egg, Peru’s environmental minister. “We need hydropower.”

But the dam will also change the Inambari’s ecosystem, already damaged by decades of logging and mining. The river level will drop, and whatever water is released will lack the nutrient-rich sediment on which the lowland wildlife—and, by extension, the Madre de Dios region—depends. Meanwhile, the 155-square-mile reservoir created behind the dam will displace about 4,000 people in at least 60 villages. And this dam is just one of dozens being planned or built in what has been called a “blue gold rush,” an infrastructure spree that is transforming the South American interior.

Development of the Amazon basin, managed correctly, could be a boon for the continent, lifting millions out of poverty and eventually bringing stability to a part of the world that has known too little of it. But in the short term it is creating new social and political tensions. How Peru balances its priorities—economic growth versus social harmony and environmental protection—will determine whether it joins the ranks of middle-class countries or is left with entrenched poverty and denuded landscapes.

Madre de Dios claims to be the biodiversity capital of the world. Fittingly, Puerto Maldonado boasts a Monument to Biodiversity. It is a tower that looms over the middle of a wide traffic circle near the center of town, with a base ringed with broad concrete buttresses, mimicking a rain forest tree. Between the buttresses are bas-relief sculptures of the region’s main activities, past and present: subsistence agriculture; rubber, timber and Brazil-nut harvesting; and gold mining—oddly human pursuits to detail on a monument to wildlife.

I was in Puerto Maldonado to meet up with an old friend, Nathan Lujan, who was leading a team of researchers along the Inambari River. After getting his PhD in biology from Auburn University in Alabama, Nathan, 34, landed at Texas A&M as a postdoctoral researcher. But he spends months at a time on rivers like the Inambari. For the better part of the past decade he’s been looking for catfish—specifically, the suckermouthed armored catfish, or Loricariidae, the largest family of catfish on the planet. Despite their numbers, many Loricariidae species are threatened by development, and on this trip, Nathan was planning to catalog as many as possible before the Inambari dam is built.

The river Nathan showed me was hardly pristine. It serves many purposes—transportation, waste removal, a source of food and water. Garbage dots its banks, and raw sewage pours in from riverfront villages. Much of Puerto Maldonado’s growth (and, though officials are loath to admit it, a decent share of Peru’s as well) has come from the unchecked, often illegal exploitation of natural resources.

Antonio Rodriguez, who came to the area from the mountain city of Cuzco in the mid-1990s in search of work as a lumberjack, summed up the prevailing attitude: “We are colonists,” he told me when I met him in the relatively new village of Sarayacu, which overlooks the Inambari. Thousands of men like Rodriguez made quick work of the surrounding forests. Mahogany trees that once lined the river are gone, and all we could see for miles was scrub brush and secondary growth. Thanks to the resulting erosion, the river is a waxy brown and gray. “These days only a few people are still interested in lumber,” he said. The rest have moved on to the next bonanza: gold. “Now it’s all mining.”

Indeed, with world prices up by some 300 percent over the past decade, gold is a particularly lucrative export. Peru is the world’s sixth-largest gold producer, and while much of it comes from Andean mines, a growing portion—by some estimates, 16 to 20 of the 182 tons that Peru exports annually—comes from illegal or quasi-legal mining along the banks of Madre de Dios’ rivers. Small-scale, so-called artisanal mining is a big business in the region; during our five-day boat trip along the river, we were rarely out of sight of a front-end loader digging into the bank in search of deposits of alluvial gold.

Less visible were the tons of mercury that miners use to separate out the gold and that eventually end up in the rivers. Waterborne microorganisms metabolize the element into methylmercury, which is highly toxic and easily enters the food chain. In perhaps the most notorious instance of methylmercury poisoning, more than 2,000 people near Minamata, Japan, developed neurological disorders in the mid- 1950s and ‘60s after eating fish contaminated by runoff from a local chemical plant. In that case, 27 tons of mercury compounds had been released over 35 years. The Peruvian government estimates that 30 to 40 tons are dumped into the country’s Amazonian rivers each year.

A 2009 study by Luis Fernandez of the Carnegie Institution for Science and Victor Gonzalez of Ecuador’s Universidad Técnica de Machala found that three of the most widely consumed fish in the region’s rivers contained more mercury than the World Health Organization deems acceptable—and that one species of catfish had more than double that. There are no reliable studies on mercury levels in the local residents, but their diet relies heavily on fish, and the human body absorbs about 95 percent of fish-borne mercury. Given the amounts of mercury in the rivers, Madre de Dios could be facing a public health disaster.

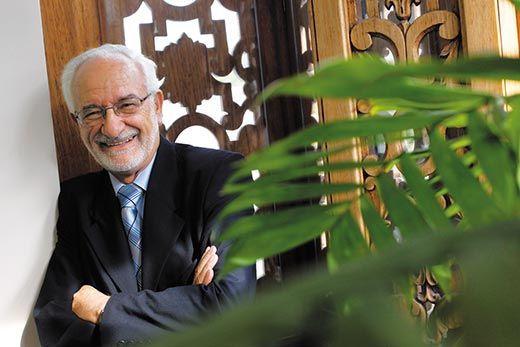

But Peru is eager to move beyond artisanal gold mining and its hazards. Over the past few decades the country has adopted a number of strict mining laws, including an embargo on issuing new artisanal-mining permits. And in May 2008 President García named Brack, a respected biologist, to be Peru’s first minister of the environment.

At 70, Brack has the white hair and the carefully trimmed beard of an academic, though he has spent most of his career working in Peru’s Agriculture Ministry. He speaks rapid, near-perfect English and checks his BlackBerry often. When I caught up with him last fall in New York City, where he attended a meeting at the United Nations, I told him I had recently returned from the Inambari. “Did you try any fish?” he asked. “It’s good to have a little mercury in your blood.”

Under Brack, the ministry has rewritten sections of the Peruvian penal code to make it easier to prosecute polluters, and it has won significant budget increases. Brack has placed more than 200,000 square miles of rain forest under protection, and he has set a goal of zero deforestation by 2021. Thanks in part to him, Peru is the only Latin American country to sign the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, an effort led by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair to make the mining industry more accountable to public and government scrutiny.

Brack has also taken over enforcement of artisanal-mining laws from the Ministry of Energy and Mining. “There are now 20 people in jail” for breaking Peru’s environmental laws, he said. A few days before our meeting, police had raided a series of mines in Madre de Dios and made 21 arrests. He told me he wants to deploy the army to protect the country’s nature preserves.

But Brack acknowledged that it is difficult to enforce laws created in Lima, by coastal politicians, in a remote part of the country suffering from gold fever. Last April thousands of members of the National Federation of Independent Miners blocked the Pan-American Highway to protest a plan to tighten regulations on artisanal miners; the demonstration turned violent and five people were killed. Brack said several police officers involved in anti-mining raids had received death threats, and the Independent Miners has demanded that he be sacked. “I have a lot of enemies in Madre de Dios,” he said.

Unlike the leftist governments of Ecuador and Venezuela, Peru and Brazil have been led, of late, by pragmatic centrists who see good fiscal management and rapid internal development as the key to long-term prosperity. By aggressively exploiting its resources, Brazil has created a relatively stable society anchored by a strong and growing middle class. Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s handpicked successor as president, says she will continue her mentor’s policies.

Lula reduced Brazil’s poverty rate from 26.7 percent in 2002, when he entered office, to 15.3 percent in 2009—accounting for some 20 million people. Peru has done almost as well: it has reduced its poverty rate from 50 percent to 35 percent, a difference of about four million people. But farming and resource extraction require lots of land and energy, which is why Brazil is expected to need 50 percent more electricity in the next decade, and Peru at least 40 percent more. In the short term, both countries will have to keep pushing deeper into the Amazon to generate electricity.

Meanwhile, they are under pressure from trading partners and finance organizations such as the World Bank to manage their growth with less environmental damage. Brazil has a bad reputation for its decades of rain forest destruction; it has little interest in becoming known as a polluter, too. With the world’s focus on limiting fossil-fuel consumption, hydropower has become the easy answer.

Until recently, Brazil had focused its hydropower construction within its own borders. But a hydropower facility works best near a drop in elevation; gravity pushes water through its turbines more quickly, generating more electricity—and Brazil is almost completely flat. Which is why, over the past decade, Brazil has underwritten mega-dams in Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru.

In 2006, Brazil and Peru began negotiating an agreement to construct at least five dams throughout Peru, most of which would sell power to Brazil to feed the growth in its southwestern states. Those negotiations produced the deal that García and Lula signed last summer.

Although Peru relies primarily on fossil fuels for its energy, Peruvian engineers have been talking about a dam along the Inambari since the 1970s. The momentum of the rivers coming down from the Andes pushes an enormous volume of water through a narrow ravine—the perfect place to build a hydropower plant. The problem was simply a lack of demand. The region’s recent growth took care of that.

But there are risks. By flooding 155 square miles of land, the proposed dam will wipe out a big chunk of carbon-dioxide-absorbing forest. And unless that forest is thoroughly cleared beforehand, the decay of the submerged tree roots will result in massive releases of methane and CO2. Scientists are still divided over how to quantify these side effects, but most acknowledge that hydropower is not as eco-friendly as it might appear. “It’s not by definition cleaner,” says Foster Brown, an environmental geochemist and expert on the southwestern Amazon at the Federal University of Acre, in Brazil. “You cannot just say it’s therefore a better resource.”

What’s more, the dam may kill much of the aquatic life below it. On my trip along the river with Nathan, he explained that freshwater fish are particularly sensitive to variations in water and sediment flow; they do most of their eating and reproducing during the dry season, but they need the high water levels of the rainy season to have room to grow. The dam, he said, will upset that rhythm, releasing water whenever it runs high, which could mean every day, every week or not for years. “Shifting the river’s flow regime from annual to daily ebbs and flows will likely eliminate all but the most tolerant and weedy of aquatic species,” Nathan said.

And the released water may even be toxic for fish. Most dams release water from the bottom of the reservoir, where, under intense pressure, nitrogen has dissolved into it. Once the water heads downriver, however, the nitrogen starts to slowly bubble out. If fish breathe it in the meantime, the trapped gases can be deadly. “It’s the same as getting the bends,” said Dean Jacobsen, an ecologist on Nathan’s team.

Others point out that if the fish are full of mercury, the local people may be better off avoiding them. In the long run, a stronger economy will provide new jobs and more money, with which locals can buy food trucked in from elsewhere. But such changes come slowly. In the meantime, the people may face massive economic and social displacement. “Locally, it means that people won’t have enough to eat,” said Don Taphorn, a biologist on the team. As he spoke, some fishermen were unloading dozens of enormous fish, some weighing 60 pounds or more. “If this guy didn’t find fish, he can’t sell them, and he’s out of a job.”

Brack, however, says the benefits of the dam—more electricity, more jobs and more trade with Brazil—will outweigh the costs and in any case will reduce the burning of fossil fuels. “All the environmentalists are crying out that we need to substitute fossil-fuel energy with renewable energy,” he said, “but when we construct hydroelectric facilities, they say no.”

A demonstration against Brazil’s proposed Belo Monte dam in March 2010 brought worldwide attention thanks to the film director James Cameron, who went to Brazil to dramatize comparisons between the Amazon and the world depicted in his blockbuster Avatar. In Peru, Inambari dam critics are now accusing the government of selling out the country’s resources and violating indigenous people’s rights. Last March in Puno province, where most of the reservoir created by the dam will sit, 600 people turned out near the dam site, blocking roads and shutting down businesses.

Nevertheless, development of the interior has become a sort of state religion, and political candidates compete to see who can promise the most public works and new jobs. Billboards along the Interoceanic Highway, which will soon link Brazil’s Atlantic coast to Peru’s Pacific coast, some 3,400 miles, display side-by-side photographs of the road pre- and post-asphalt and bear captions like “Before: Uncertainty; After: The Future.”

President García has spoken forcefully against indigenous and environmental groups that oppose projects like the Inambari dam. “There are many unused resources that cannot be traded, that do not receive investment and do not create jobs,” he wrote in a controversial 2007 op-ed in El Comercio, a Lima newspaper. “And all this because of the taboo of past ideologies, idleness, laziness or the law of the dog in the manger that says, ‘If I do not do it, then let no one do it’ ”—a reference to a Greek fable about a hound that refuses to let an ox eat a bale of hay, even though the dog can’t eat it himself.

Last June, García vetoed a bill that would have given local tribes a say in oil and gas projects on their territory. He told reporters he would not give local people veto power over national resources. Peru, he said, “is for all Peruvians.”

Even in the Peruvian Amazon, the dam enjoys wide support. A poll of local business leaders in the Puno region found that 61 percent were in favor of it.

On my fourth day on the Inambari, I met Albino Mosquipa Sales, the manager of a hotel in the town of Mazuco, just downriver from the dam site. “On the whole it is a good thing,” he said of the dam. “It will bring economic benefits like jobs and commerce,” plus a new hospital promised by the state electrical company. Mosquipa’s caveats were mostly procedural: Lima should have consulted with local populations more, he said, and the regional government should have pushed harder for concessions from the dam builders. It was a line of complaint I heard often. People questioned whether the electricity should go to Brazil, but not whether the dam should be built.

Eventually I made it to Puente Inambari, a postage-stamp-size village of perhaps 50 buildings that will be destroyed when the dam is built. I had expected to find anger. What I found was enthusiasm.

Graciela Uscamaita, a young woman in a yellow long-sleeved shirt, was sitting in a doorstep by the side of the road. Her four young boys played beside her. Like virtually everyone I had met on the trip, she had the dark skin and prominent cheekbones of an Andean highlander. And, like the other local residents I talked to, she was happy about the hospital and the new houses the government has offered to build them farther uphill. In the meantime, there was the possibility of getting a job on a construction crew. “It will be better for us,” she said. “It will bring work.”

Clay Risen wrote about President Lyndon Johnson for the April 2008 issue of Smithsonian. Ivan Kashinsky photographed the Colombian flower industry for the February 2011 issue.