In 1976, when prolific writer, activist and self-described Black lesbian mother warrior poet Audre Lorde published her seminal poetry collection, Coal, the world wide web was still 17 years away from becoming a public-facing invention, and the platform of podcasting hadn’t even been dreamt up yet. The volume established her as a champion for women, Blackness, queerness and equity in the explosive 1970s Black Arts Movement—other works to come, like Sister Outsider, positioned Lorde as a justice-demanding mouthpiece for people who’d been shoved into the crosshairs of marginalization.

She was highly quotable and, in recent years as discussions about mental health and the prioritization of personal peace have become more frequent and fervent, one of her most notable lines of writing has become its own celebrity: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” From that sentence, knit into the reflective context of A Burst of Light, Lorde’s award-winning contemplation on the healthcare system and the cancer that had invaded her body, the concept of “self-care” was popularized and made real.

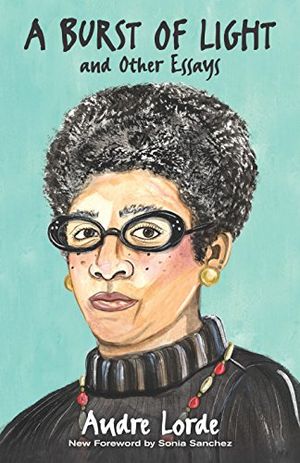

A Burst of Light and Other Essays

From reflections on her struggle with the disease to thoughts on lesbian sexuality and African-American identity in a straight white man's world, Audre Lorde's voice remains enduringly relevant in today's political landscape.

Like many terms that originate in the canon of Black art and thought, self-care has been swallowed into a vortex of mainstream overuse and lack of attribution.

In too many cases, when we don’t know where a heavily used term came from, we’re inadvertently failing to acknowledge the intellectual, theoretic and academic contributions of Black women scholars, thinkers and creatives. In 2022, the African American History Curatorial Collective at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History inaugurated the podcast project, “Collected,” co-hosted by curators Krystal Klingenberg and Crystal Moten. “Collected” sets out to reconnect these terms to their historical roots, bringing fresh light to the work of Black feminist writers and activists. “We are re-rooting Black feminism and placing it in its original historical context,” explains Moten in the podcast.

“We noticed that in the public discourse, particularly in media and social media, there are several Black feminist terms, ideas and practices floating around,” says Klingenberg, a curator of Black music and entertainment in the museum’s division of cultural and community life, in an interview after the series debuted earlier this year. “But they’re always disconnected from the Black feminist thinkers who created them, the context in which they were created, and in some instances, from the very meaning that the original creators were thinking of when they created them.”

“We saw how ideas like ‘intersectionality’ or ‘self-care’ were just being used haphazardly in situations where, if you knew the history and the context, you began to question a little bit: ‘Is this appropriate?’ We wanted to address some of the disconnect we see between how these ideas and practices are being used and provide some historical context to connect them back to their original creators,” says Klingenberg.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9b/b3/9bb3b3db-59db-49f5-89fb-a6bdd4cb0f58/gettyimages-993469504.jpg)

“Collected” is a six-episode excavation of Black feminism, but it’s also a broad platform for the women who, like Lorde, have been doing the work before technology made learning as easy as typing into a search bar. The creative process that shaped “Collected” was robust and included interviews with additional experts—there were ten of them altogether, including Paris Hatcher, an activist and a self-described Black feminist rabble rouser; the author and scholar Brittney Cooper, the political strategist and film maker Charlene Carruthers and the award-winning writer and editor Raquel Willis.

Following the introduction, episode 2, “Collective Re-rooted,” explores the landmark Combahee River Collective, named for the location where Harriet Tubman planned and led a military campaign that freed more than 750 slaves. Episode 3, “Identity Politics Re-rooted,” traces the term’s origins. Episode 4, “Self-Care Re-rooted,” dissects the remixing of Lorde’s original meaning of self-care and its evolution into self-pampering which, guest Feminista Jones adds, is “a social work buzz word that people have exploited…something marketable and something that can be profited from.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/47/0c47d51a-1827-407f-8fbf-fbfa7c250d7e/gettyimages-907803092.jpg)

The work of legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw is discussed in the episode “Intersectionality Re-rooted” and “The Future of Black Feminism Re-routed” brings many of the panelists together for a final analysis.

For Klingenberg and Moten, curators turned media co-hosts, the first season of “Collected” has also been an opportunity to explore their shared interest in podcasting and knead the often high-level, scholarly topic of Black feminism into conversational, easily digestible 20-minute episodes.

“The Smithsonian is known for its exhibitions, but we put all this love and care into making sure that the material from this podcast is really accessible and understandable. Podcasting was definitely a different direction for us and for the museum, and we're really proud of where we've landed with it,” says Moten, a curator of African American business and labor history in the museum’s division of work and industry.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/66/b166d694-a708-427d-ae3f-17ee596a6561/gettyimages-933489188.jpg)

“Anytime you talk about a theoretical topic, it can get kind of heavy,” Klingenberg says. “Crystal and I are recovering academics and professors, so we were concerned that we might get a little too in the clouds with some of this material. And it felt good to think, ‘OK, we really understand what we're doing now.’ Over the production process, we just continued to grow in our roles as writers, editors and podcasters.”

Together, she adds, she and Moten worked to take listeners on a journey. Both curators describe themselves as ideas people, so the possibility of a second season to expound on their investment in the first is enticing to both. For now, they’re still soaking in the euphoria of a finished product that hit all of its desired marks to connect theory and practice.

“My ultimate, best, favorite interview was with Barbara Smith,” Moten said. “Hearing her narrate the emergence of the Combahee River Collective, her own activism and why it was so important, and how she sees the work of Combahee and Black feminism resonating today, it just strengthened my heart in a way that I wasn't expecting. I think this whole project did.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/25/f7/25f7ff15-7a4c-4652-8102-f32f058c1849/gettyimages-1077484580.jpg)

In 1977, the women of the Combahee River Collective released a groundbreaking statement “defining and clarifying” the politics of Black feminism. It was also arguably the first time that the phrase “identity politics” would appear, and Smith is credited with coining the term.

“We were not saying that we were superior to any other groups of oppressed people,” says Smith in the podcast. “We were not being a vanguard. We did not think that we were the only people on Earth who were oppressed. We just wanted to assert that unlike the women’s movement and unlike the Black liberation movement at that time, that there was a particular set of situations, circumstances and experiences and oppressions that Black women experienced, and that we needed to deal with those. And that’s what we meant by identity politics.”

In the podcast, Moten outlines the four parts of the Combahee River statement: “So the first part discusses the genesis or the origins of contemporary Black feminism. The second part discusses what the Combahee River Collective believed in in terms of their politics. The third part goes on to addressing the problems in organizing Black feminists, including a brief history of the collective, and then the last part discusses Black feminist issues and practice.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/66/5666f201-c5a7-40eb-96a2-d246bc3c0456/ta2019_38_1_1_1_6_001-2.jpg)

Using the popular form of a podcast for the purposes of delving further into the history of the profound nature of selfcare as a political act; expanding on the deep heritage of the Combahee River Collective, the origins of political identity; and appreciating intersectionality as the impact of compounded racism—has had its challenges, say the curators, but the results have been rewarding.

“Although I'm a historian who’s been studying Black women's history and theory for decades, I still came to this like, I want to get this right,” says Moten. “Speaking with our guests and hearing their heartfelt passion for Black feminism and Black feminist theory is one of the most important things I've done in my career so far.”

Find additional transcripts, episode notes and resources on the “Collected” website. The podcast, a project of the African American History Curatorial Collective, was produced in partnership with Smithsonian Enterprises Digital Studio and the production team Jenna Hanchard, Taylor Polydore, Ann Conanan and Alana Gomez and funded by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1650x1131:1651x1132)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/41/fd/41fddb51-8467-4e7b-b6a7-79427ea7d94b/gettyimages-129594565.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/janelle.png)