Writing New Chapters of African American History Through The Kinsey Collection

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520110629Portrait-by-Artis-Lane_medium-224x300.jpg)

Bernard and Shirley Kinsey have been married 44 years. Since Bernard's retirement in 1991 from the Xerox corporation, the couple has traveled extensively, collecting art from around the world. But in an effort to uncover their own family history, the Kinseys began to delve into African American history and art. This has become their primary area of interest, and over the years they have acquired a wealth of historical objects, documents and artworks, from shackles used on an African slave ship to a copy of the program from the 1963 March On Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

A group of artworks and artifacts from the Kinsey Collection comprises the next exhibition in the National Museum of African American History and Culture's gallery in the American History Museum. The Kinseys have also published a book—The Kinsey Collection: Shared Treasures of Bernard and Shirley Kinsey-Where Art and History Intersect—which accompanies the exhibit and includes the objects on display as well as several supplementary pieces in their collection. I spoke with Bernard Kinsey about the exhibit, which opens this Friday, October 15, and will be on display through May 1, 2011.

What first inspired you and your wife to begin collecting objects from African American history?

We live our lives on two simple principles: To whom much is given, much is required and a life of no regrets. We started with $26 and a job in 1967 right out of college. And my wife and I decided that we were going to live on one paycheck and save the rest. My wife, Shirley, worked for 15 years and never spent a dime of her paycheck. We saved it and we bought property and made investments, which allowed us to retire while still in our forties in 1991 and to do the two things we love most, which is to travel and to collect art. We've been to 90 countries. And we want to share our blessings—we've raised $22 million for charities and for historically black colleges. We've sent or assisted more than 300 kids to college. And we embarked on telling this story of the African American experience through dedicated research about the history that has not been told about our people.

But we started African American collecting in a serious way when Khalil, our son, came home with a book report on family history. We couldn’t go past my granddaddy. We knew immediately that we needed to do something about that.

Tell me a bit about your collection. What kind of narrative is represented?

This is a story about the Kinsey family and how we see and experience the African American culture. We’ve gone out all over the world to try to integrate all this stuff in a collection that says, “Who are these people that did so much that nobody knows about?”

Josiah Walls was the first black congressman from the state of Florida in 1871. This brother owned a farm in Gainesville, Florida, in the 1860s, after the Civil War, and worked at Florida A&M University, our alma mater. Walls fought three different election recalls to be elected and died in 1902 in obscurity. And we did not have another black congressman in the state of Florida until 1993. All three from Florida A&M, all classmates of mine. What we try to do also, all through the exhibition, all through the book, is emphasize the importance of black colleges, the importance of our churches, the importance of our community organizations.

Ignatius Sancho, he was a bad brother. Born on a slave ship, and he was the first brother to be picked by the Duke of Montague to see if black people had the cranial capacity to be human. So he picked this brother, and he goes on to become a world famous opera singer, entrepreneur. And he’s the first African to vote in an election in England. Nobody knows about him. Obscurity.

Everybody knows about Phylis Phillis Wheatley. Her name came from the slave ship Phillis, she was bought by the Wheatley family, so she’s Phillis Wheatley. She comes here at seven years old, speaks no English. In two years she speaks English, Greek, and Latin. In four years, she’s playing the piano and violin, and in seven years, she writes the first book written by an African American in this country, and couldn’t get it published in America, had to go to England. And this is at the height of our revolution. 1773. So what we want to do is say there’s another side to this picture called America. And that side is a people that have done extraordinary things.

What is the competition like for acquiring these objects and artworks?

The most competitive auctions are African American stuff. I just got this catalog the other day. The African American section could be about four or five pages, and it will be fierce. They have the Dred Scott decision, 1858, at 4 p.m. on the 14th of October. I’m going to be on that. If you’re going to do this, you have to play at a very high level. There are a lot of people that collect African American history, no question about it. And I think all of it is fine, but there are certain documents that make a difference. And if you have those documents, it says everything about that particular historical moment. So that’s what we’ve tried to do.

The Equiano book, the only written account of someone who experienced the actual horror of being on a slave ship for five months, it took me a year of talking to this guy before he would tell me he had three Equianos. He’s a Princeton professor, and we never met other than on the phone. He died before I was able to buy the book. His wife called me and said that he had died, and we began to negotiate. I ended up purchasing the book, and since then I’ve purchased two of the three books. You see these books once every 35 to 40 years. You see them when someone dies. Because most families don’t know what this stuff is. Imagine that this was just in a room, and you walked in. Unless you knew what it was, you’d just think it was a piece of paper.

Do you have any recommendations for people who are interested in getting into their own backgrounds and family histories?

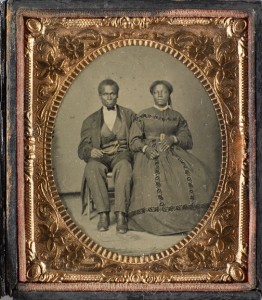

First of all, everybody has a family history. We suggest that everybody start interviewing their grandparents and their aunts and uncles, and holding on to those photographs and writing on the back who they are and their relationship, doing family trees, doing your DNA. Those are things that we all can do, because in fact, you don’t need an exhibition to be able to know who you are or where you came from.

So have you discovered anything about your personal family history?

Yes. Carrie Kinsey. There’s a book called Slavery By Another Name, by Douglas Blackmon who won the 2009 Pulitzer prize for nonfiction. It’s a powerful book. It’s about the early 1900s when slavery had been abolished, but it became big business to put young black males in the prison system and the chain gang system for free labor. On page eight, they talk about this black African American woman, 1903, named Carrie Kinsey, and I immediately knew this was my family. See, we never could find out where this Kinsey name came from. But there are two big plantations in Bainbridge, Georgia: the McCree plantation and the Smith plantation. And we believe that that really is where we all came from.

One of the wonderful things about collecting is that you really are discovering history. It’s not like all history has been discovered, because it hasn’t. The African American story has been brutalized because of racism and discrimination. And much of African American history or what is written about our ancestors never spoke to their extraordinary contributions in building what we know as America. We’re writing new chapters everyday.

“The Kinsey Collection: Shared Treasures of Bernard and Shirley Kinsey–Where Art and History Intersect” is presented by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and on view in the museum's gallery at the National Museum of American History from October 15 through May 1, 2011.

(This post was updated on 10/14 to offer more information about the exhibition.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jess-righthand-240.jpg)