Why Our Oceans Are Starting to Suffocate

A new paper links global warming to diminished oxygen concentrations at sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/97/8f97335d-7cef-480d-bc3b-ad9a08b5258b/o2.jpg)

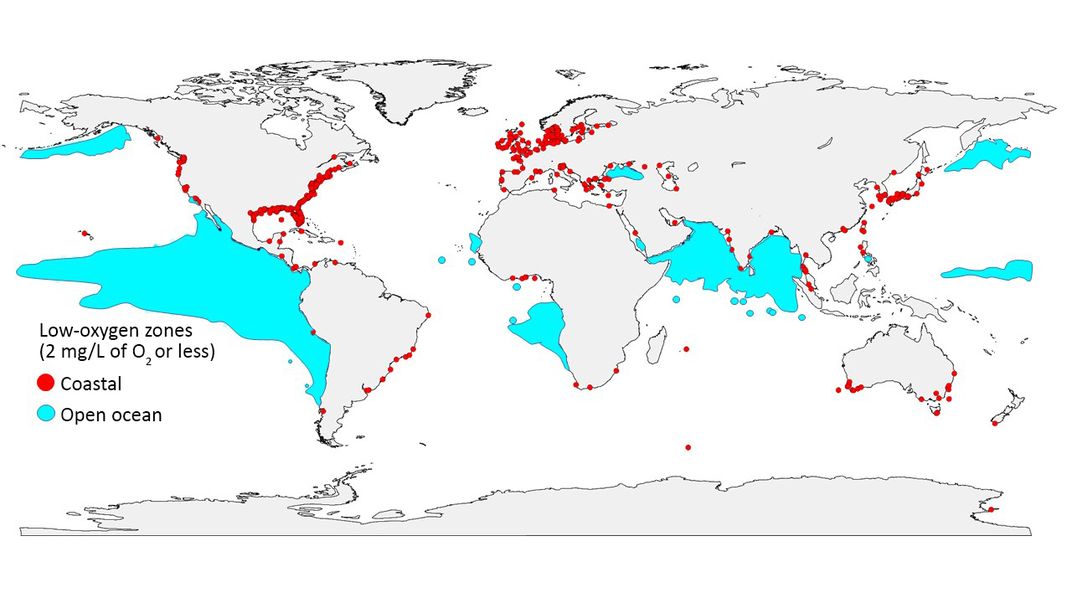

When it comes to animal life on Earth, oxygen is a baseline necessity. From humans and housecats to gorillas and great white sharks, the simple diatomic molecule is essential to the success of cellular respiration, which breaks down complex carbohydrates to produce the energy required for survival. A recently published article in Science magazine reports that all across the globe, oxygen content in our oceans is dropping—rapidly.

The synthesis piece, titled “Declining Oxygen in the Global Ocean and Coastal Waters,” is the collaborative work of nearly two dozen authors, each bringing to the table specific research expertise. The international organization UNESCO brought together the diverse scientific team in an effort to call attention to an issue of growing severity and deserving of wider recognition. A synoptic document drafted by the scientists with U.S. policymakers in mind will soon be making its way to Capitol Hill. It will serve well as a layperson-friendly complement to the more technical Science publication.

At the heart of the oxygen crisis is an unfortunate double-whammy effect tied to rising ocean temperatures, which themselves are linked to greenhouse gas emissions on the part of humans. For one, the solubility of oxygen is inversely correlated with water temp, so when ocean water gets hotter, the oxygen in the air does not dissolve as readily, meaning that there is less to go around for aquatic lifeforms. To add insult to injury, higher water temperature elevates the metabolic rates of sea creatures, so their bodies crave more and more oxygen as less and less is available.

“It’s increasing oxygen requirements,” says Denise Breitburg, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland, and first author on the Science paper, “and at the same time, oxygen is declining.”

Breitburg and her colleagues have observed all manner of invidious effects in anoxic, or abnormally oxygen-poor, marine environments. In many cases, algae and other simple organisms that don’t need as much oxygen to survive proliferate at the expense of complex organisms. And gamete production among those complex organisms—needed for successful reproduction—can also be adversely impacted by low oxygen levels, such that once a population begins to drop off, its disappearance can quickly turn precipitous.

Another trait of anoxic ocean environments, Breitburg notes, could exacerbate global warming trends yet further if action is not taken. “They’re sites of production of compounds like nitrous oxide,” she says, “which are really potent greenhouse gases. So there is the potential for feedback that may worsen climate change.”

What can be done about declining oxygen levels in the world’s water? Breitburg maintains that, in the case of an issue as massive and wide-ranging as this—in which atmosphere-warming fossil fuel consumption and industrial practices surrounding sewage and nutrient runoff are the chief culprits—meaningful change can only develop through action at the institutional level.

“The scale of the problems is large enough,” says Breitburg, “that, although individual actions are important, it really takes larger-scale effort to solve them.” She is confident that we as a nation have the means at our disposal to tackle many of the major issues—we need only muster the will to act.

“In terms of nutrient pollution,” she says, “we definitely have the ability and the technology to deal with that problem. It can be expensive, but the longer we wait and the worse the problem gets, the larger the magnitude of the problem we have to deal with, and the higher the cost.”

Breitburg is similarly adamant that greenhouse gas emissions—responsible for the lose-lose effect on ocean life described earlier—must be curbed in the immediate future if progress of any kind is to be made. “We have no choice, really, but to address that problem,” she says.

At the end of the day, Breitburg recognizes that dissolved oxygen levels in seawater is but one slice of a much larger pie. Her aim is to make sure that it is a slice that is properly acknowledged by the media and the public, and one that will serve as a valuable case study for legislators looking to make a difference.

“The consequences of climate change go way beyond just the potential for declining oxygen in the oceans,” she says, “and really include all aspects of Earth’s ability to support life. The steps that are needed are not easy, but we have no choice.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)