Whigs Swigged Cider and Other Voter Indicators of the Past

Throughout most of American history, what someone wore indicated their political affiliations as loudly as a Prius or a Hummer might today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/a4/bea4de17-b223-41b8-b4c5-d51e03282135/wide-awakes.jpg)

It shouldn't work this way, but it does. You can often tell someone's most deeply held political beliefs from the cut of their pants, the car they drive or their choice of liquor. Long before data-crunching algorithms, Americans relied on cultural cues to tell who voted how. And wearing the wrong hat to the wrong polling place could get you into serious trouble.

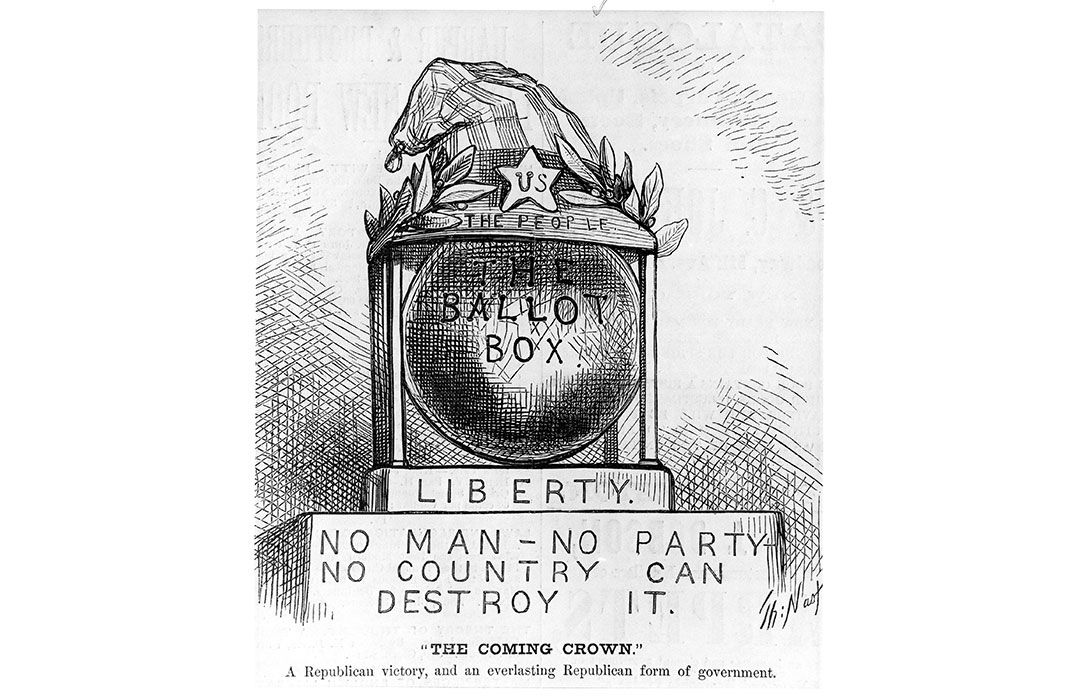

The vast collections of the National Museum of American History hold the largest trove of these encoded artifacts. Their messages are hard to decipher today, but screamed political ideology as loudly in 1800 or 1920 as driving a Prius or a Hummer might today. Clothes indicated a great deal, but so did choice of alcohol. And many of the museum’s best artifacts allude to the politics of cider, porter, lager or whiskey drinkers. All demonstrate that American politics has long esposed a certain aesthetic identity.

It began with the Revolution. As Americans debated how to govern their new country, a war broke out between those who wore two different kinds of ribbons called cockades. Federalists preferred black cockades, signaling their support for a powerful centralized government. Republicans sported tricolor (red, white and blue) ribbons, associated with a smaller government and the radical French Revolution.

Soon boys were hassling men wearing the wrong cockade in the streets, while partisan women placed the ribbons on their bodices, daring men to object. Then the fights started. In Massachusetts, a young man with a tricolor cockade on his hat made the mistake of attending a Federalist church. The congregants waited until services ended, then jumped him, beat him and tore up his hat. In Philadelphia, a brawl among butcher boys wearing different cockades ended with many thrown in jail. Finally, when Republicans won out after 1800, rowdy crowds held symbolic funerals for the black cockade.

As American politics developed, politicians used their hats, their wigs and their canes to hint at their alliances. Leaders hoped that looking respectable would make them seem virtuous. Their clothes also indicated membership in political factions. One group of populist New Yorkers stuck deer-tails to their hats. These men, called the Bucktails, formed the nucleus for the Democratic party, identified by their fashion before their new movement even had a name.

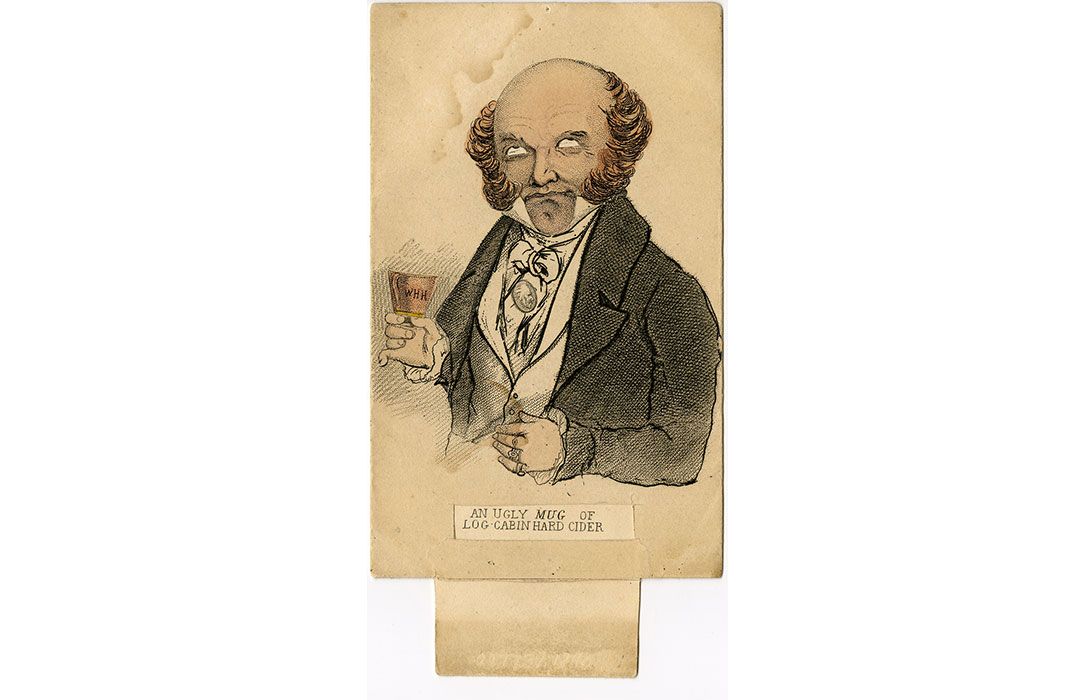

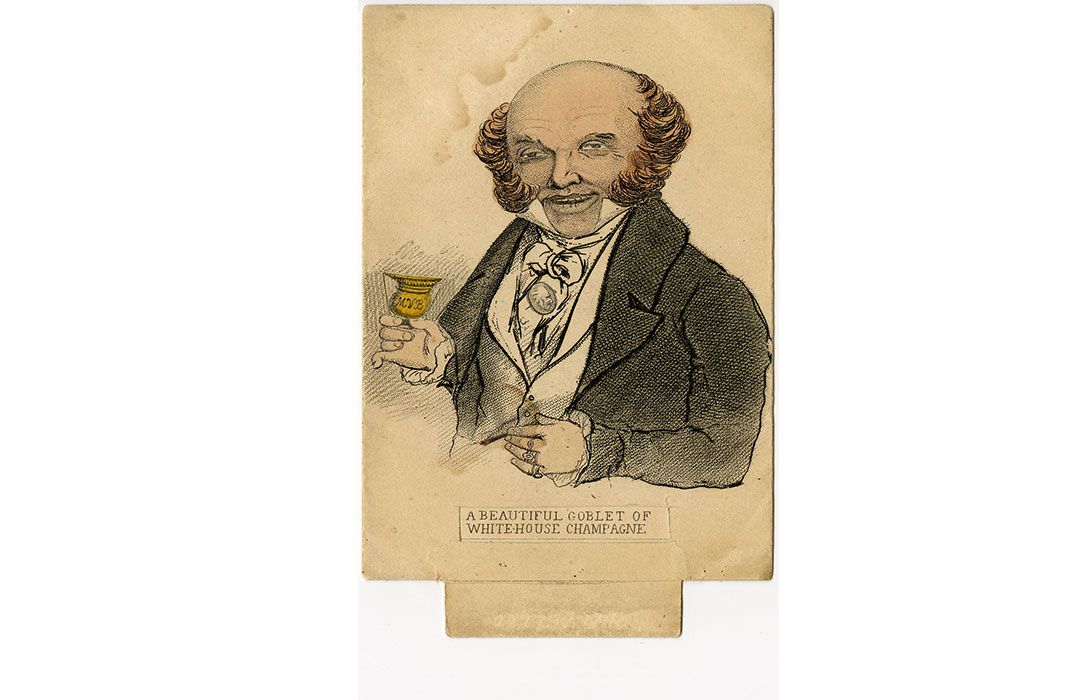

As politics became more democratic, parties battled to identify with the common man and depict their rivals as the "silk-stocking party." In the wild 1840 election, the new Whig party dressed its campaigners in fringed leather hunting shirts and handed out flagons of hard cider. The Democrats pushed back, rolling forth barrels of porter beer. By the end of that campaign, Americans swore you could tell a person's party by what they ordered in the tavern. Gulping cider was as good as wearing the "badge of a political party." This dressed-up campaign drew one of the highest voter turnouts in American history.

Political gangs employed fashion to menace rivals. In the 1850s, a violent anti-immigrant movement targeted migrants fleeing Ireland, just as cheap clothing let citizens accessorize their ideologies. In cities like New York and Baltimore, anti-immigrant supporters of the Know Nothing movement strutted the avenues in red shirts, leather vests, high boots and precarious stovepipe hats. Irish gangs, working as enforcers for the Democrats, had their own uniforms of baggy coats and red or blue striped-pants. Life on city streets meant constantly deciphering the codes hidden in the hats or coats of the rowdies and the dandies lurking under the gaslights.

These stereotypes had very real impacts on election day. There was no good system for registering voters, instead each party sent bullies to "challenge" illegal voters. Really, these partisans read fashion cues to try to cut anyone who was about to vote the wrong way. In big cities and tiny hamlets, challengers judged every aspect of a man's appearance—his clothes, his beard, his job, his address—to guess how he'd vote. They listened to his accent— Was that an Irish Catholic or a Scotch-Irish brogue?—and intimidated (or, occasionally, murdered) men who showed up to vote in trousers favored by the rival party.

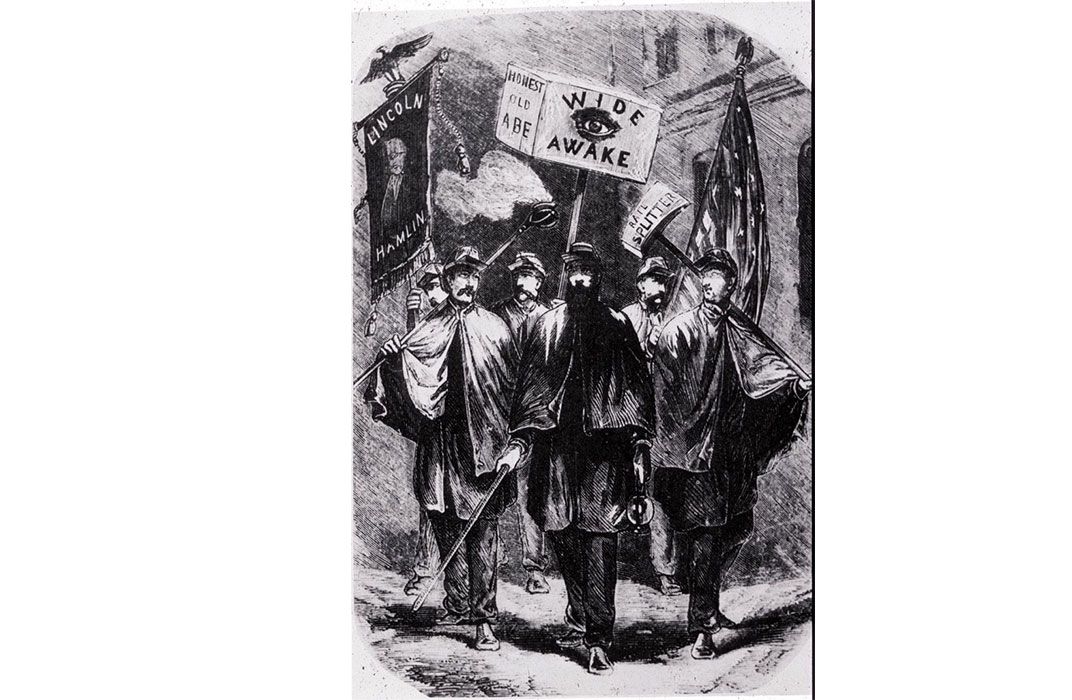

During the Civil War, northerners read each others outfits just as closely. To help Lincoln win the presidency, young Republican men joined "Wide Awake clubs," parading by torch-light in shiny cloaks and military caps. Later, Confederate-leaning Northerners who hated Lincoln and his war were often called "Butternuts," a throwback to the Midwestern settlers who came from the South and wore clothing dyed using butternuts to the color of khaki. "Copperheads," another name for Confederate-sympathizers, became so hated that to call someone "copper" was a challenge to a fight.

During the years after the Civil War, white and black Southerners used their clothing to declare their politics as well. African-Americans organized the semi-secret Union League clubs, to help protect freed slaves' first votes. Union League members wore sashes and used secret handshakes and hand-signals. Racist white Southerners debuted the Red Shirts, men who terrorized black voters. While the Ku Klux Klan operated in secret, men in homemade red shirts openly obstructed southern polling places, their clothing a clear threat to African-Americans voters. By the end of Reconstruction, Red Shirts ruled in much of the South.

The quality of one's clothes could signal their party as well. In an increasingly unequal society, tramps and hoboes in ragged tweed and busted derbies were assumed to be supporter of the radical Populist party, while chubby gentleman in staid suits leaned Republican. Machine politicians played these assumptions. One Tammany Hall district boss swore that over-dressing could kill a Democratic political career: voters were naturally suspicious of a candidate in a fancy suit. Choice of alcohol mattered too. Around 1900, the boss advised politicians in Irish-dominated cities to stick to good-old Irish whiskey. Swigging lager implied that a man was too German, too radical, and probably spent his days "drinkin' beer and talkin' socialism."

Of all the colors that carried political implications—black, copper, red—yellow shined the brightest, symbolizing the long struggle for women's right to vote. Starting with prairie-state suffragists who associated themselves with the sunflower, suffragettes used bright, flashing yellow to identify their movement in the early 20th century. They donned yellow costumes, often accented with royal purple borrowed from English suffragettes, to create bold displays in huge demonstrations. By the time women won the right to vote in 1920, planting yellow roses made a strong statement of support for women's rights.

In the mid-20th century, it became harder to stereotype voters by their clothes. Declining partisanship and general consensus between the parties meant you often couldn't tell who backed Kennedy or Nixon, in 1960, for instance. Political scientists found that those voters were worse at distinguishing between the parties than at any other time studied, so it made sense that few dressed the part. There were still clues, as always, tied to race, region and class, but for much of the mid-20th century they became less stark.

In more recent years, political fashion has steadily been on the rise. Hippies and hardhats, bra-less supporters of the Equal Rights Amendment and bow-tied young Republicans declared their beliefs in the 1970s or '80s. By the 21st century, increased partisanship makes this even easier. We all notice the subtle signifiers that seem to declare one's politics.

On one level, there is something disheartening about this, as if our beliefs could be reduced to team colors. But political fashion makes a positive statement as well. Throughout American history, our democracy has not been limited to official organizations or partisan media, but lives in American culture, as vibrant and intimate as the clothes on our backs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)