Welcome to Blackdom: The Ghost Town That Was New Mexico’s First Black Settlement

A homesteading settlement founded out of reach of Jim Crow is now a ghost town, but postal records live on to tell its story

![]()

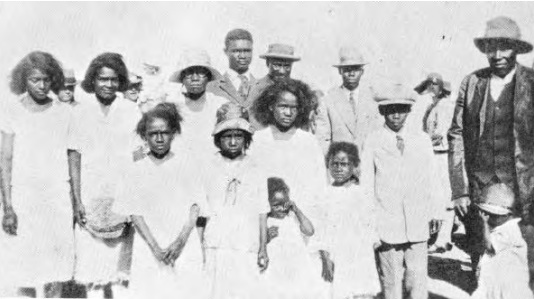

A Sunday school class at Blackdom Baptist Church, circa 1925. Courtesy of the Museum of New Mexico

In the early 1900s, a small utopian settlement of African American families took shape in the New Mexico plains about 20 miles south of Roswell. Founded by homesteader Francis Marion Boyer, who was fleeing threats from the Ku Klux Klan, the town of Blackdom, New Mexico, became the state’s first community of African Americans. By 1908, the town had reached its zenith with a thriving population of 300, supporting local businesses, a newspaper and a church. However, after crop failures and other calamities, the town by the late 1920s had rapidly depopulated. Today little remains of the town—an ambitious alternative to the racist realities elsewhere—except a plaque on a lonely highway. But a small relic now lives on at the National Postal Museum, which recently acquired the postal account book kept for Blackdom from 1912 t0 1919.

“Here the black man has an equal chance with the white man. Here you are reckoned at the value which you place upon yourself. Your future is in your own hands.”

Lucy Henderson wrote these words to the editor of The Chicago Defender, a black newspaper, in December, 1912, trying to persuade others to come settle in the home she had found in Blackdom. She said, “I feel I owe it to my people to tell them of this free land out here.”

Boyer traveled more than 1,000 miles on foot from Georgia to New Mexico to start a new life and a new town in the land his father once visited during the Mexican-American War. With a loan from the Pacific Mutual Company, Boyer dug a well and began farming. Boyer’s stationery proudly read, “Blackdom Townsite Co., Roswell, New Mexico. The only exclusive Negro settlement in New Mexico.” Though work on the homesteading town began in 1903, the post office would not open until 1912.

A sketch of Blackdom’s town plan. Courtesy of Maisha Baton and Henry Walt’s A History of Blackdom, N.M., in the Context of the African-American Post Civil War Colonization Movement, 1996.

David Profitt house, a typical house in Blackdom, New Mexico. Courtesy of the Museum of New Mexico

When it did, Henderson was able to brag to Chicago readers, “We have a post office, store, church, school house, pumping plant, office building and several residents already established.”

“The climate is ideal,” Henderson claimed in her letter. “I have only this to say,” she went on, “any one coming to Blackdom and deciding to throw in their lot with us will never have cause to regret it.”

By the late 1920s, the town was deserted, after a drought in 1916 and less-than-plentiful yields.

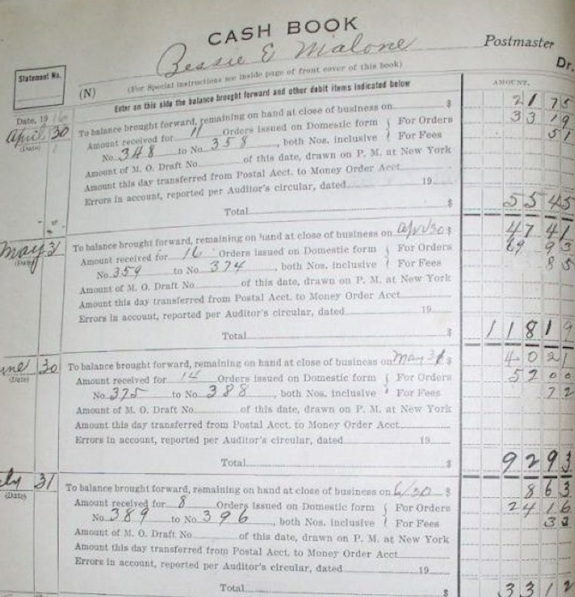

Blackdom’s cash book was passed down by three different postmasters, including the town’s final postmaster, a woman named Bessie E. Malone. Courtesy of the National Postal Museum

Blackdom’s post office. Courtesy of New Mexico PBS

The post office spanned nearly the entire life of the town, operating from 1912 to 1919. Records in the account book detail the money orders coming in and out of Blackdom. “When you look at a money order,” explains Postal Museum specialist Lynn Heidelbaugh, “particularly for a small community setting itself up, this is them sending money back home to their homes and families and setting up their new farms.”

Though Blackdom did not survive and never expanded to the size Lucy Henderson may have hoped, black settlements like it were common elsewhere during a period of migration sometimes called the Great Exodus following the Homestead Act of 1862, particularly in Kansas. According to a 2001 archaeological study on the Blackdom region from the Museum of New Mexico, “During the decade of the 1870s, 9,500 blacks from Kentucky and Tennessee migrated to Kansas. By 1880 there were 43,110 blacks in Kansas.”

Partly pushed out of the South after the failures of Reconstruction, many of the families were also pulled West. The report goes on, “Land speculators used a variety of methods in developing a town’s population. They advertised town lots by distributing handbills, newspapers, and pamphlets to a target population. They sponsored round-trip promotional excursions that featured reduced rail fares for Easterners and offered free land for schools and churches.”

The towns had varying degrees of success and many of the promises of paid passage and waiting success proved false. Still, the Topeka Colored Citizen declared in 1879, “If blacks come here and starve, all well. It is better to starve to death in Kansas than to be shot and killed in the South.”

After the Blackdom post office closed, the money book was handed off to a nearby station. The book sat in the back office for decades until a savvy clerk contacted a historian with the Postal Service, who helped the document find a new home at the Postal Museum, years after its old home had vanished.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)