Illuminating the Treaties That Have Governed U.S.-Indian Relationships

These documents were both a cause and a salve for the fraught relations between the United States and Indian Nations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/ee/6aeeecdf-04c1-432d-a1b8-ef39a44fe2df/uneasypeace-1.jpg)

As president in the 1790s, George Washington said he resented the “jobbers, speculators and monopolizers” who were creating a threat to his young republic by cheating Indians out of land. His army was fighting Indians in the Ohio Valley, and a powerful alliance of six Indian nations in New York State was warning that there were what the Seneca leader Red Jacket called “rusty places on the chain of friendship” between them and the United States.

So in 1794, Washington dispatched his postmaster general, Timothy Pickering, to renew peace with the Haudenosaunee, or Six Nations (the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca and Tuscarora). The resulting Canandaigua Treaty affirmed the nations’ right to their lands and established “firm peace and friendship” between them and the United States. It also bound the U.S. to make a one-time payment to the nations of $10,000, plus annual payments of $4,500 in goods, including calico cloth, which the Indians prized for use in regalia. To commemorate the agreement, Washington commissioned a six-foot-long wampum belt showing 13 figures, representing the states, linked with figures representing the Haudenosaunee. The Six Nations still have it.

The so-called Calico Treaty, one of the earliest the U.S. entered into, is still in force: Every July, the Bureau of Indian Affairs dispatches what amounts to a square yard of cloth per tribal citizen to the tribes (except the Mohawks, because the U.S. has come to believe that no Mohawk leaders were present at the treaty’s signing).

“With so many broken treaty promises by the U.S. government, the fact that we still get the cloth is significant,” says Robert Odawi Porter, former president of the Seneca Nation. “The catch is that the treaty cloth is purchased with monies the sum of which is fixed in the treaty.” So the cloth, Porter says, is now thin muslin. “We half-jokingly threaten to bring a breach-of-trust claim against the government for higher-quality fabric,” he says. “Our ancestors forgot to ask for a [cost-of-living] adjustment, I guess.”

The real value of the cloth, Porter says, is symbolic. “As Indians, we must continue to fight to hold the U.S. government accountable for the promises that it made to us, no matter how small or insignificant those promises may seem to some,” he says.

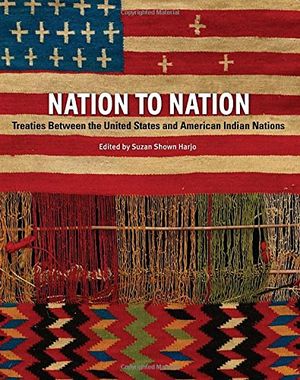

The Canandaigua Treaty is one of eight major compacts that will be featured in “Nation to Nation: Treaties between the United States and American Indian Nations,” an exhibition opening at the National Museum of the American Indian September 21. The treaties, to be displayed serially for six months each, will be accompanied by more than 100 photographs and other artifacts that reflect the fraught history between the United States and its indigenous peoples.

“These tribal-federal treaties were critical to a very fragile, young American nation, helping to secure the borders from European competitors,” says museum director Kevin Gover, a Pawnee and co-curator of the exhibition with Suzan Shown Harjo, a Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee advocate for Indians. “They created a nation-to-nation relationship that lasts until this day. Even though it has its ups and far too many downs, it is still there, and the opportunity is still there for the U.S. and the Indian nations to thrive together.”

Kevin Washburn, assistant secretary for Indian affairs at the Department of the Interior, says, “Federal Indian policy has changed over time, but treaties are the most important reflection of the government-to-government relationship with tribes.” The annual distribution of the treaty cloth, he says, is “a reflection of the importance of the Treaty of Canandaigua.”

“It’s kind of funny and really sad,” adds Sid Hill, tadodaho (chief) of the Onondaga Nation. “They keep sending this cloth—less each year, of lesser quality over time—yet they have broken so many other treaties and promises involving our lands, sovereignty and human rights.” And yet Hill is gratified that the history behind the treaty will be highlighted. “Our elders wanted this story to be known,” he says. “They didn’t care if the cloth ended up being the size of a postage stamp. If it was still being given, it meant the treaty was still in place.”

The exhibition, "Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations," is on view at the National Museum of the American Indian September 21, 2014 through summer of 2018.