From big ears to sex scandals, the paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures on display in the Smithsonian’s singular exhibition “America’s Presidents” at the National Portrait Gallery—the only public collection to feature portraits of every chief executive—share with their subjects the ability to draw controversy.

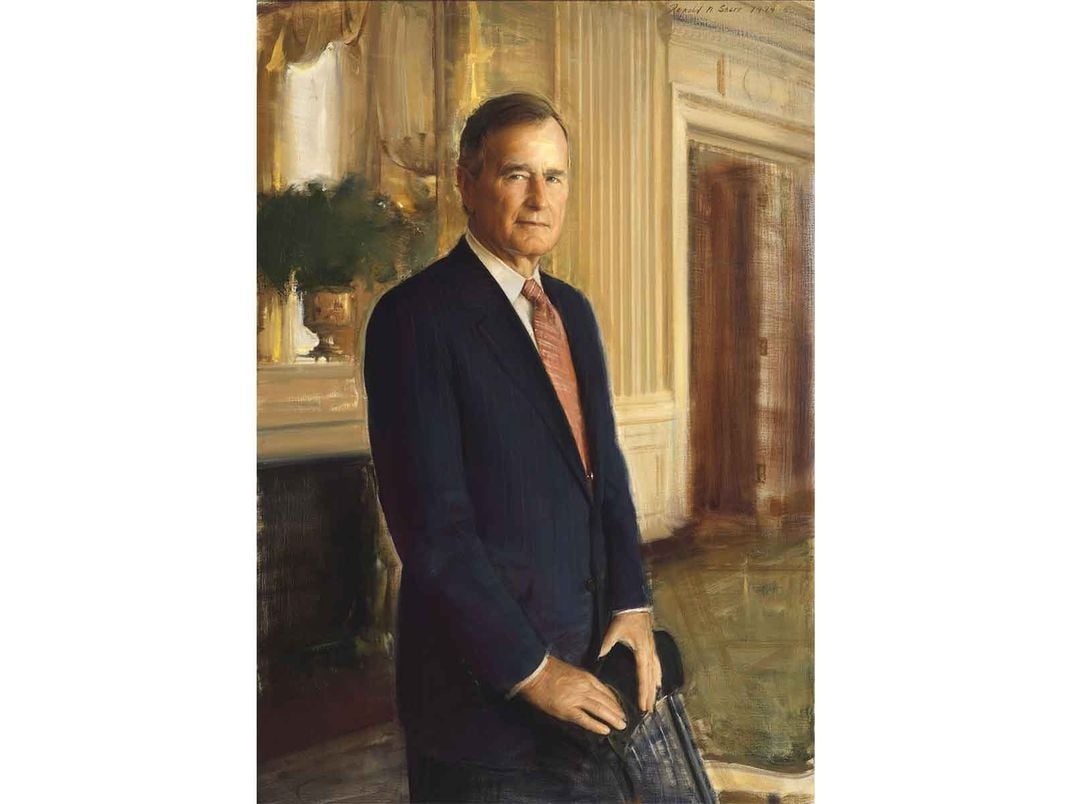

When the museum first opened in 1968, it owned just 19 portraits of the then-35 presidencies, and as a result, officials launched a major effort to find portraits of the others as an essential step toward opening a presidential gallery. Purchases helped to fill the gap, but in 1994, the museum began commissioning its own portraits, with the first capturing an image of George H.W. Bush.

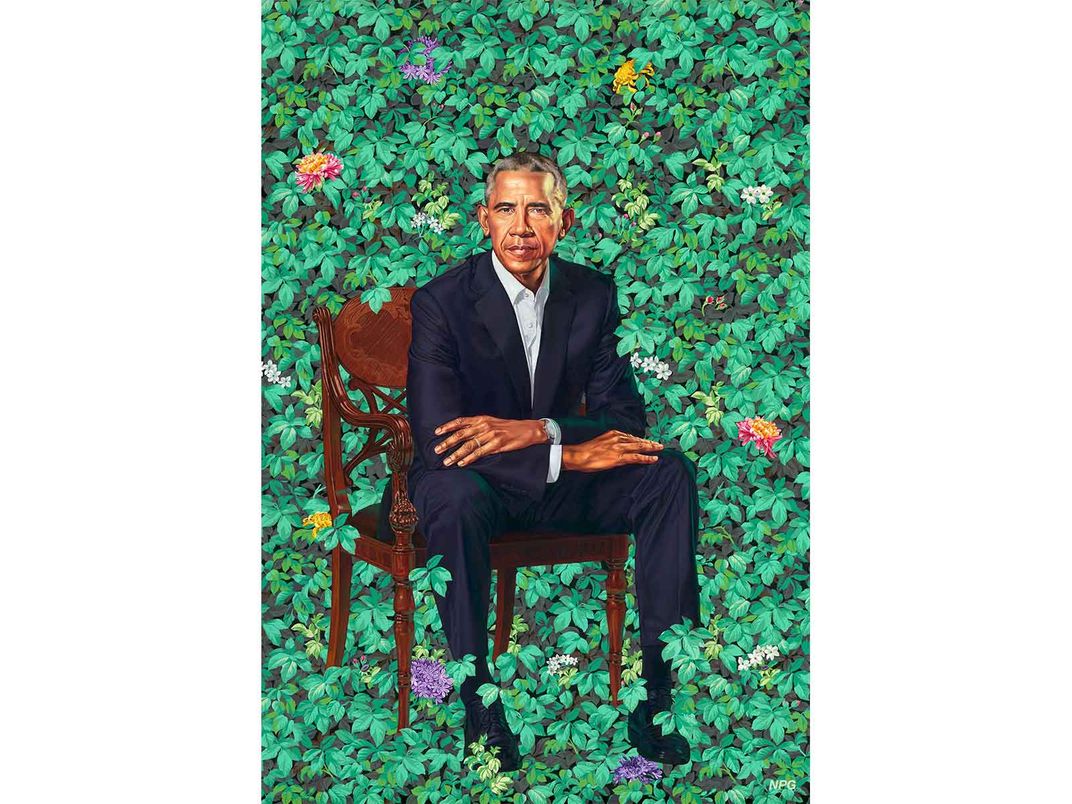

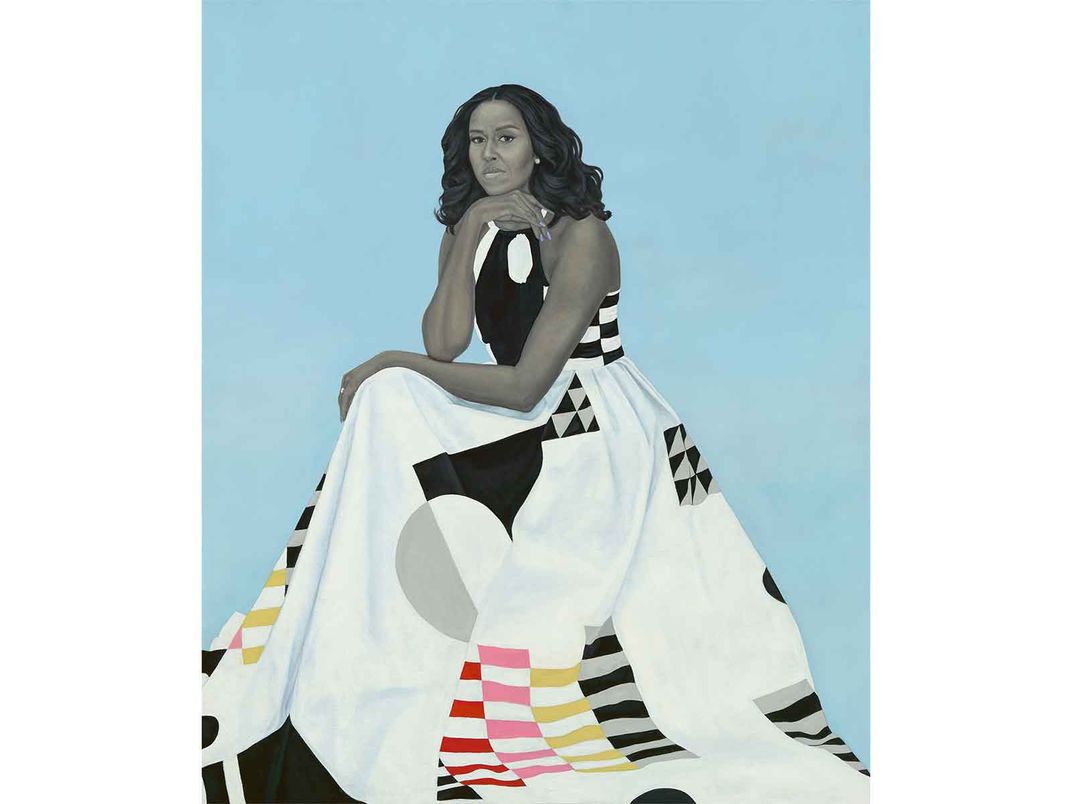

Since then, first showings of these images have become “a major event,” says the museum’s director Kim Sajet. “In 2018, when we unveiled the Obamas’ portraits by Kehinde Wiley [who painted Barack Obama], and Amy Sherald [who provided an image’s portion of Michele Obama], our annual attendance doubled to over 2.3 million visitors.”

Once the museum reopens following the months-long Smithsonian-wide closure for Covid concerns, Sajet says a portrait of the former President Donald J. Trump will go on view until the official painting of the nation’s 45th leader is commissioned and unveiled.

In the museum’s recent episode of its podcast “Portraits,” Sajet spoke candidly with the Pulitzer Prize winning Washington Post art and architecture critic Philip Kennicott, about the complex process of populating the museum’s signature installation.

Listen to the podcast

"Portraying Presidents"

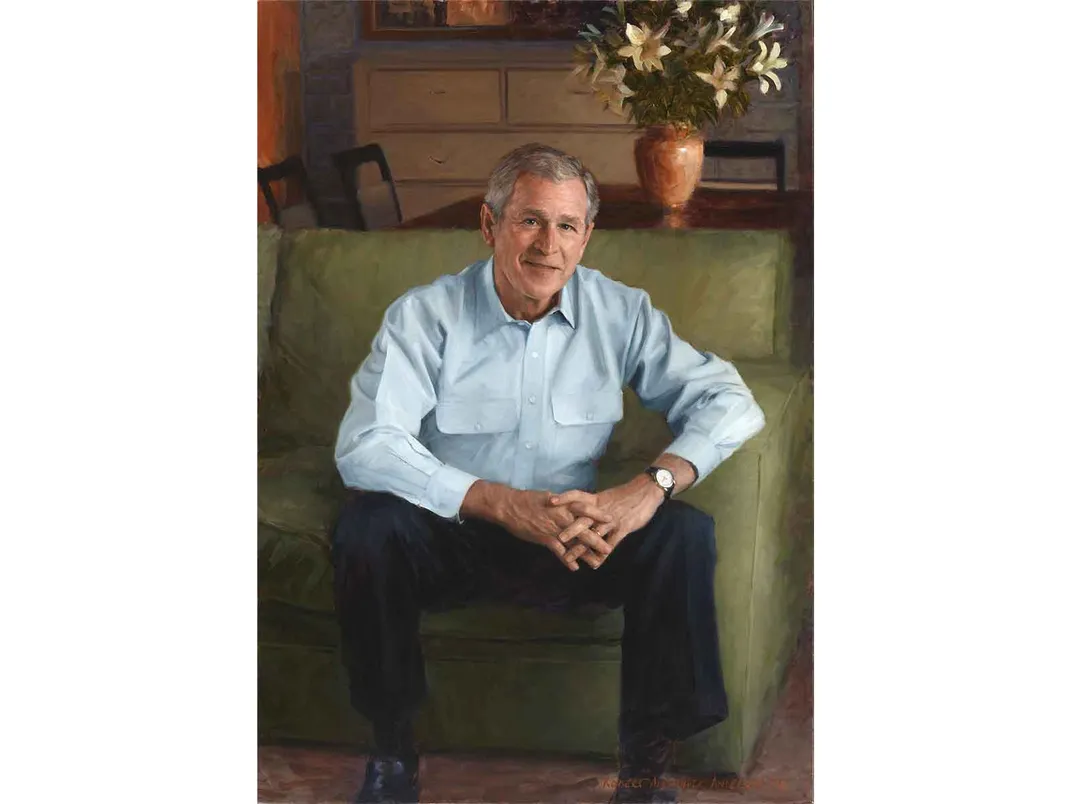

Former presidents participate in the official unveilings as they take their places among their predecessors, and often, their comments are telling. “I suspected there would be a good-sized crowd, once the word got out about my hanging,” joked former President George W. Bush. He also said that the artist, Robert A. Anderson, “had a lot of trouble with my mouth, and I told him that makes two of us.” At the time of his painting’s debut, Obama said, “I tried to negotiate less gray hair, smaller ears,” but he admitted failure on both counts.

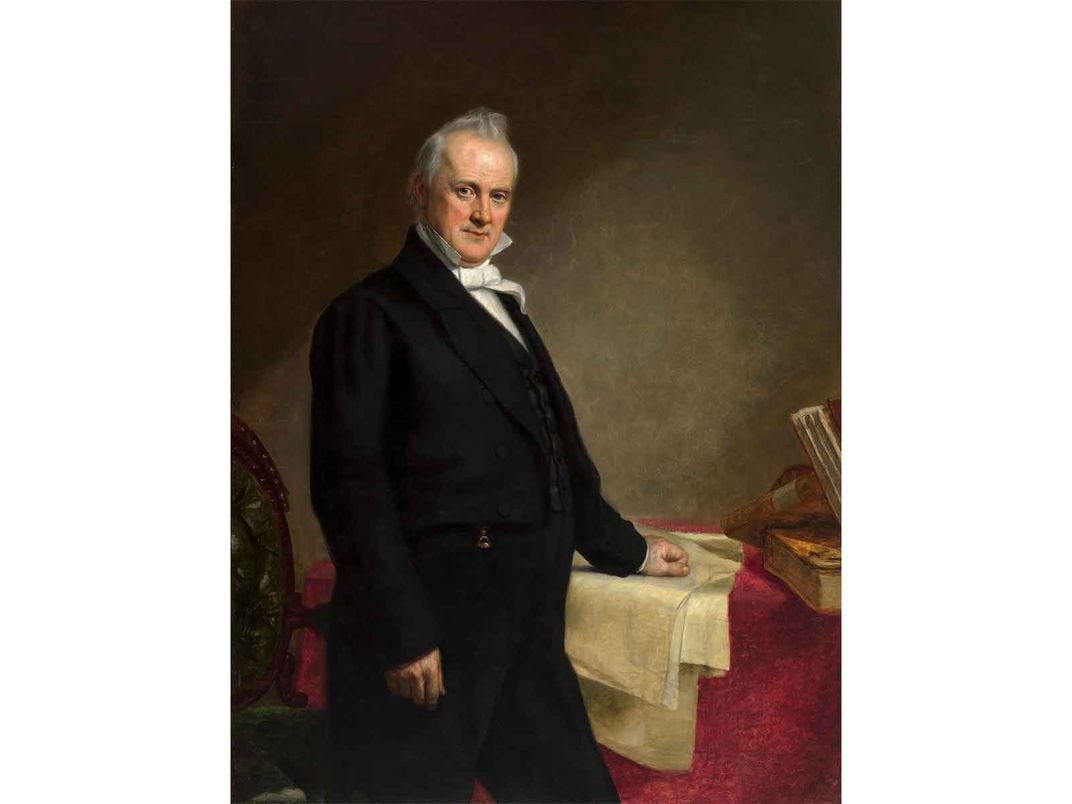

Often, the portraits pique viewers’ curiosity about what message they pose and what background they are meant to convey. George Peter Alexander Healy, who produced six paintings of the missing 19th century presidents, made one of James Buchanan. The 15th president was a proponent of U.S. expansion through the acquisition of Alaska, Cuba, and Mexico, and is generally credited with setting the stage for the Civil War. In Healy’s portrayal, Buchanan stands by a desk covered with papers, including maps. The portrait “shows a pretty self-satisfied feckless guy dressed really nicely,” notes Kennicott.

Buchanan’s failed presidency is captured in the museum’s carefully crafted label: “Buchanan did little to prevent the first seven Southern states from seceding. The Civil War broke out April 12, 1861, only a few weeks after he had left office.” Sajet notes that at least 12 presidents* all enslaved other humans; and that many led wars and executed cruel imperialistic moves against Native Americans to expand the United States under the misguided policy of “Manifest Destiny.”

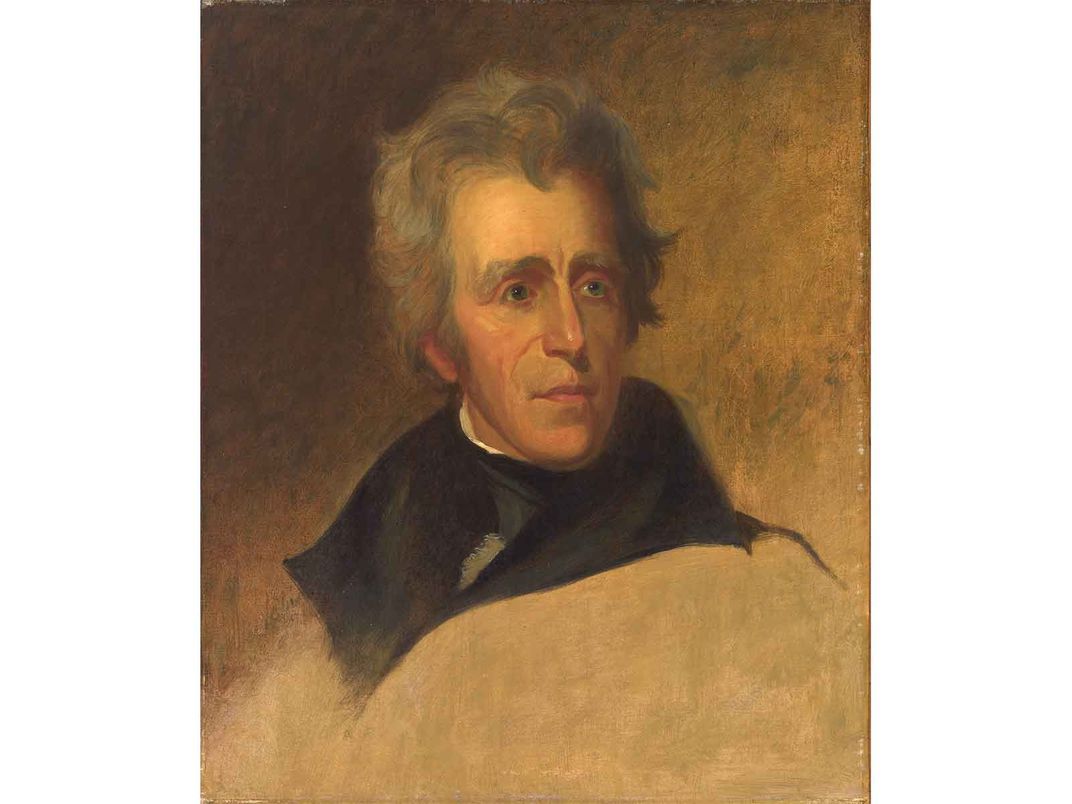

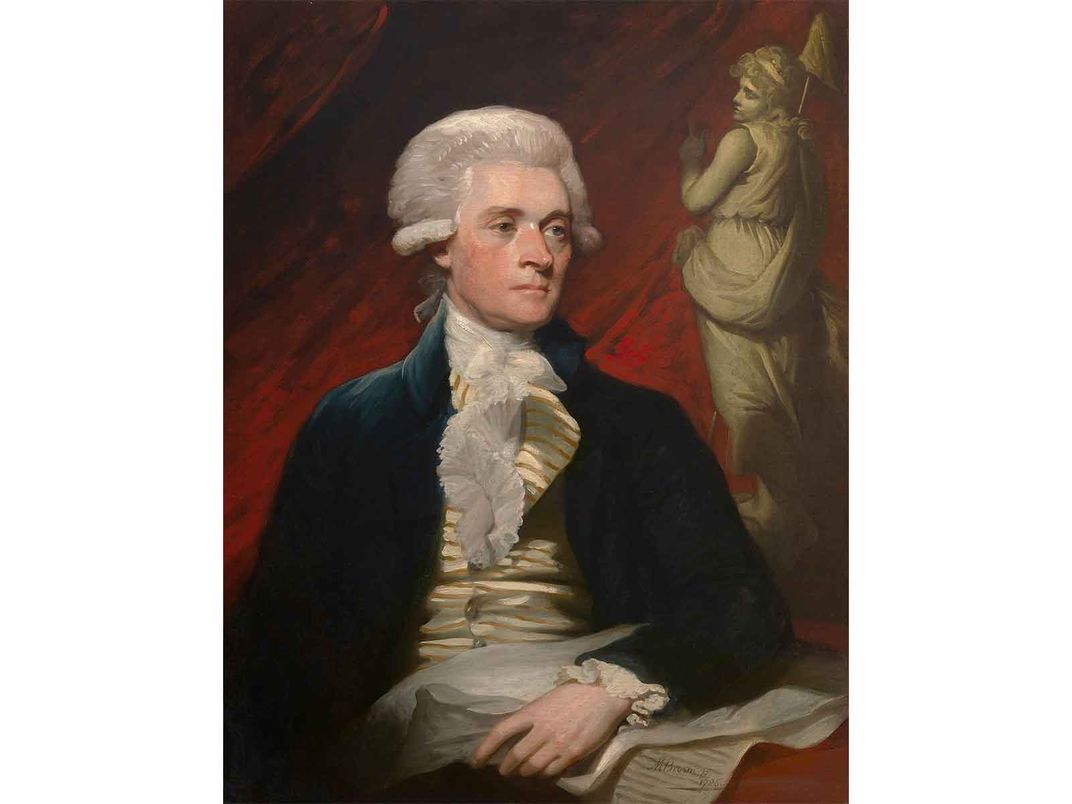

The portraits of Thomas Jefferson, who ran a brutal slave-labor system at Monticello, and Andrew Jackson, who aggressively acted against Native Americans, are both romanticized images. “You don’t sense a monster in either of those faces,” says Kennicott. “As we know more and more about Jefferson, as we know more and more about Jackson . . . . [museum visitors] are going to want to argue with that,” Kennicott believes. “We have to undo the purposeful effort to make them into who they were not.”

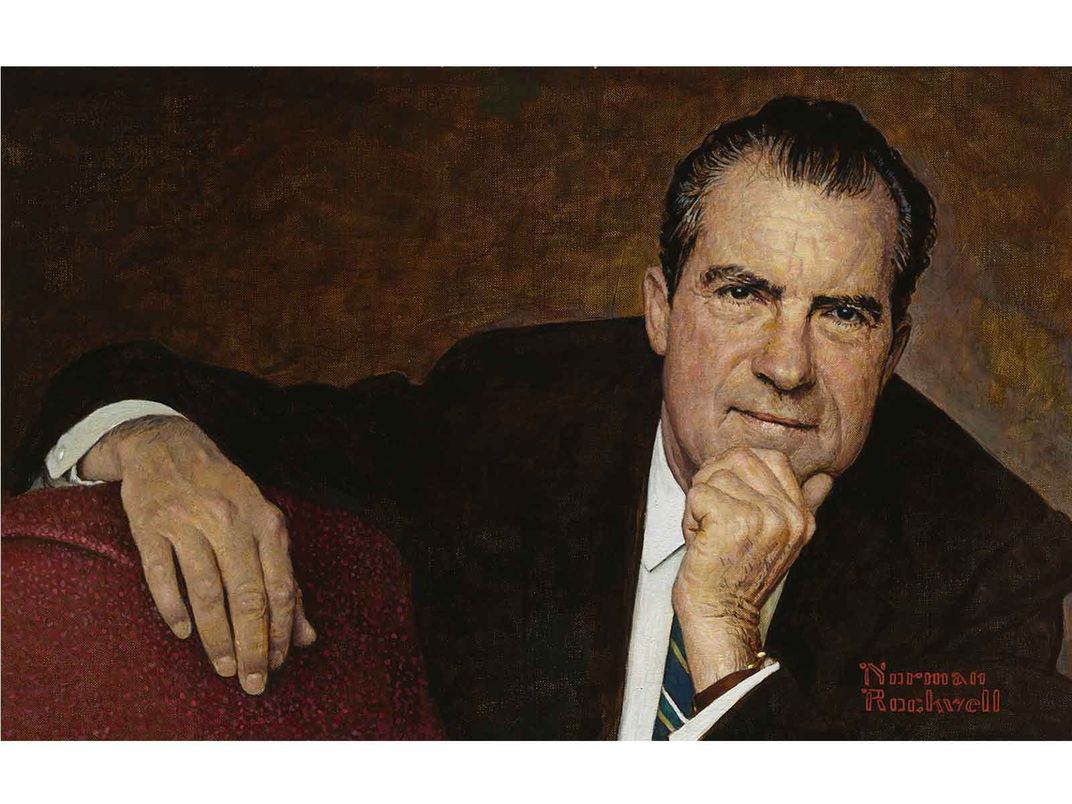

Sajet has found that museum visitors often identify political messages, either implicit or explicit, in the portraits. The 1968 Norman Rockwell illustration of Richard Nixon, the first and only president to resign the office, is much smaller than others in the gallery because it first appeared on the cover of Look magazine after Nixon won his election. For that reason, some have wondered whether the size of his portrait reflected a conscious effort to minimize him as a result of the Watergate scandal. It does not, says Caroline Carr, former deputy director and chief curator of the museum. Carr tells the story of when the artist Robert Anderson was beginning to work on the portrait of the 43rd president George W. Bush. He asked museum employees to take a measurement from the portrait of the head of Bush’s father, the 41st president George H. W. Bush. The artist wanted the two portraits to be proportionally similar; and they do hang near each other, Carr says.

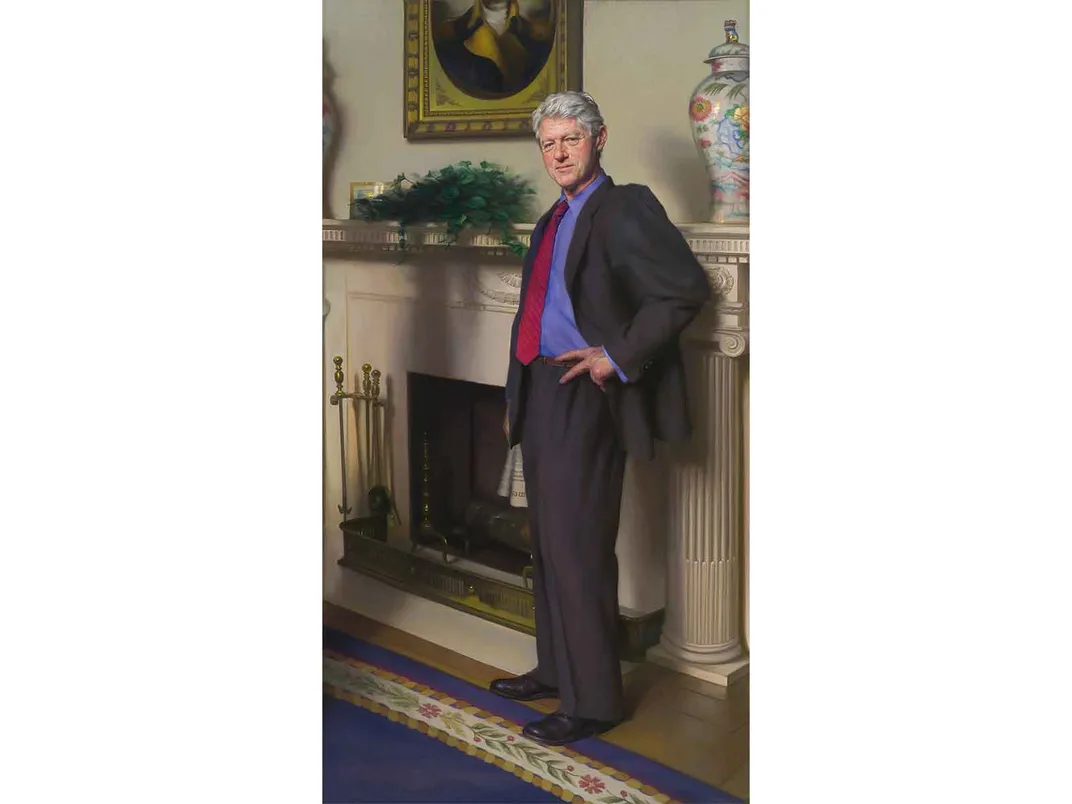

To date, Bill Clinton’s portrait has sparked the greatest controversy among the commissioned images. The process of producing the portrait was not smooth; Clinton said that he was too busy for two sittings, so the artist used a mannequin to imagine the president’s shadow. According to Carr, three members of Clinton’s staff who traveled down from New York to look at the portrait, thought Clinton’s hands lacked elegance and that the casual brown shoes he wore should be replaced with the classic English black leather shoes that Clinton preferred.

On the surface, the image appears conventional. He stands next to a fireplace mantle, with a painting and vases behind him. “And he has the Clinton swagger,” notes Kennicott. “He’s got his hand on one hip. He’s looking straight at you. There’s definitely a sense he could step right out of this painting and glad-hand you and talk you out of ten bucks before you even knew what happened—a mixture of that kind of consummate politician, car salesman charisma.”

The furor over the portrait came nine years after the its 2006 unveiling. In an interview with the Philadelphia Daily News, the artist, Nelson Shanks, created a new narrative, saying that he had hidden a reference to the sex scandal involving Clinton and White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Shanks said that he had painted the shadow of Lewinsky’s dress in the background. The artist, who died shortly after making this revelation, said: “The reality is he’s probably the most famous liar of all time. He and his administration did some very good things, of course, but I could never get this Monica thing completely out of my mind and it is subtly incorporated in the painting.”

Shanks’ declaration took the public by storm. “That was such a bizarre chapter. . . It felt like a parting shot in some ways,” says Kennicott. “When he said that, he was really kind of dropping a bomb. It was also just a classic idea of control over the image.” Kennicott sees Shanks as someone who became disillusioned about Clinton. “You paint this image, years go by, and you see the kind of glow of hagiography settled over this person that you were trying to represent in one particular way. . . .[and you think]: Let me put back into this image what you all seem to have forgotten or erased from it, and I’m going to do it in shadow.”

However, neither Kennicott nor Sajet can find anything in the portrait suggestive of the scandal. “Who knows if he really meant that to be a shadow in the beginning!” says the journalist. “I don’t know that the artist gets to have the last word on that.”

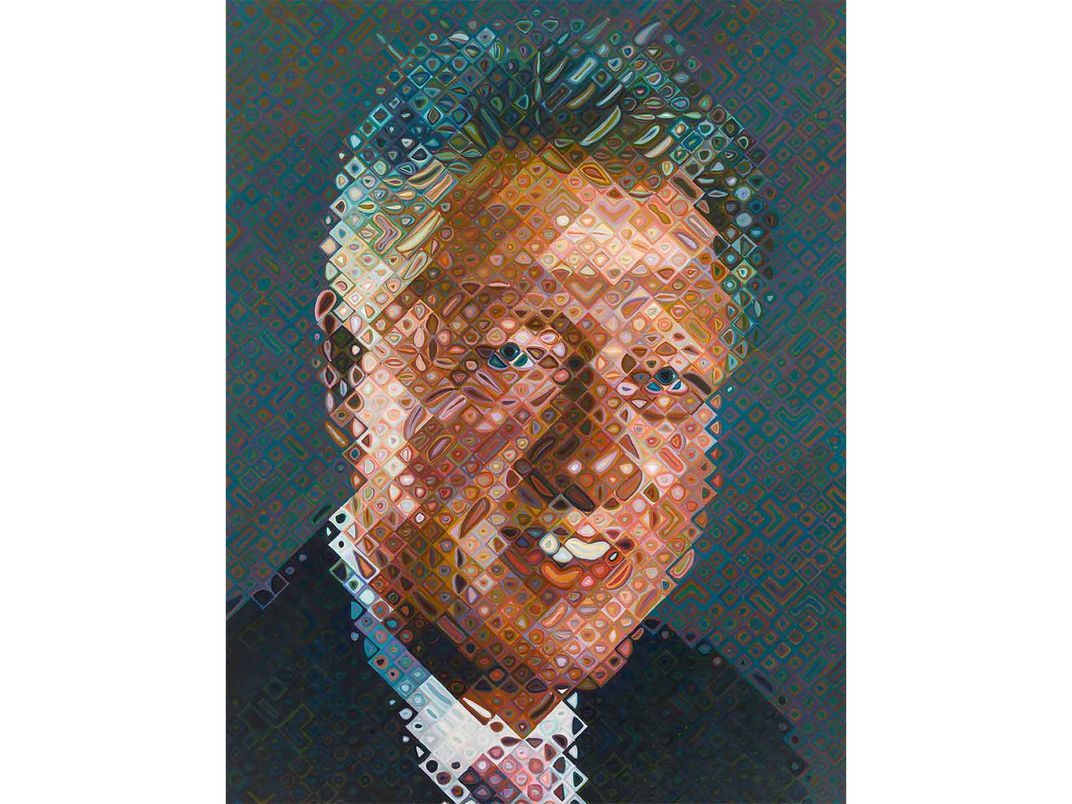

He adds that viewers of the portrait are not “obliged to see that shadow in the painting if we don’t want to see it.” Shanks also made an omission in the portrait that some viewers noted: He did not show Clinton wearing a wedding ring. That, the artist said, was simply a mistake. Right now, the portrait in question is not on display in the museum, which has in its collections about ten portraits of Clinton that can be rotated for periods of time. The Clinton image that is hanging in the exhibition is by artist Chuck Close and was based on a photograph.

Even the Obama portraits, which Sajet labels as “wildly popular” and showstoppers, generated some concerns. Kehinde Wiley, who created the image of President Obama, often pictures Africans and African-Americans in regal European settings. And President Obama was a bit concerned about seeing himself on a throne or a horse, but the final portrait avoided any suggestion of royalty. Both conventional and surreal, it shows the 44th president sitting in a chair that is drifting within a tropical background, Kennicott says. At the same time, he notes that people view the Obama portraits differently than others. “They go not just to see a portrait of Michele Obama hanging in a gallery of first ladies: They go to be in her presence.” (Beginning in June, the portraits of Barack and Michele Obama will begin a five-city tour to Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta and Houston.)

Given the possibility of controversy over presidential portraits, not to mention the policies implemented by the Trump administration, it is not surprising that some people have raised questions about commissioning a portrait of the only president to be impeached twice. The second time, Kennicott reminds listeners, was for inciting the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. “We’re getting a lot of people saying, ‘Well, let’s skip over a president.’” Sajet says. She wonders “What is that delicate balance, particularly when it comes to presidents who are elected by the people in a democratic society, what is the role in that balance between veracity of knowledge and art and display?”

Kennicott thinks you have to look at the museum and how it functions as an influencer. “A lot of people who come to your building, they want it to be not just a museum about portraiture and paintings, with this side thing about politics. They want it to be a hall of fame, a place of honorifics. So does he deserve a place in a museum if we think of it as a hall of fame or a place of honor? There’s a good argument to say no.... But if we’re thinking about the museum having both a political and an artistic agenda, then it’s a very different thing.”

As Sajet says, “There’s no moral test to be in the Portrait Gallery. Otherwise, nobody would be there.”

Trump not only will join the figures in the “American Presidents” exhibition: Like his predecessors, he will have the opportunity to choose the artist to produce an image and the final product will represent his presidency, among the portraits of others who represent the contemporary presidency.

Kennicott believes the National Portrait Gallery does something the capital’s memorials and official buildings don’t do: It creates “the illusion of being face-to-face with power in a much more intimate way.”

The museum is “a place where you get both an official narrative and an invitation to go beyond the official narrative,” he says. “It hopefully makes people conscious about official narratives in a way that they aren’t if they just accept official narratives as true.”

"The Obama Portraits Tour" journeys to The Art Institute of Chicago, June 18 through August 15; the Brooklyn Museum, August 27 through October 24; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 5 through January 2, 2022; the High Museum of Art, January 14, 2022 through March 13, 2022; and The Houston Museum of Fine Arts, March 27, 2022 through May 30, 2022.

Editor's Note, April 6, 2021: A previous version of this article, along with the podcast, incorrectly stated that the first 12 presidents all enslaved humans. John Adams, the second president, however, did not; though he and his wife Abigail may have employed individuals enslaved by others to staff their household while living in the White House. Both the podcast and this article have been updated.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/7c/d77cee0e-b5ff-42f9-aa08-99ea5ac90d9c/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/6f/736fd91a-e9ca-4839-a9bb-b89ab0097171/longform_desktop1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)