These Photos of Deconstructed Devices Reveal Their Hidden Beauty

Engineer-artist Todd McLellan finds marvel in blowing out the mundane

When young Todd McLellan first smashed a Dinky die-cast model car to smithereens—his tool of choice a simple hammer—he taught himself a lesson that would stick with him for decades: deconstruction can be constructive.

McLellan, now an accomplished photographer and avid engineering hobbyist, discovered early on the wonder of taking an object apart, of separating out every piece and arriving at a baseline understanding of how they combine to form a whole.

Both static and kinetic visions of disassembled hardware populate McLellan’s new exhibition, now on view at South Carolina’s Upcountry History Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate through February 19, 2017. The show will then hit the road traveling to Kansas City first on an ambitious 12-city national tour.

The targets of the Canadian tinkerer’s frequent dissections range from alarm clocks and radios to telescopes and Swiss Army knives—any technology, modern or archaic, is fair game. As far as acquisition goes, McLellan’s strategy is straightforward: roam his Toronto neighborhood and see what devices he can pick up on the cheap.

“People are willing to put a lot of stuff out on the street,” McLellan says in a recent interview. He likes to keep an open mind. After all, it’s not as though there’s necessarily anything defective about an MP3 player or a classic turntable left by someone’s curb.

“They were just tired of having them around,” he says. “Or they bought a brand new one.”

McLellan is also a regular patron of local thrift shops. But many of his subjects are culled from a private collection of second-hand tchotchkes—items he himself has used in his own life. One beloved clock of his has been disassembled, reassembled, and then disassembled again. “And now there’s no getting it back together,” McLellan muses. “It’s in an inch of acrylic.”

At this point in his curious side-career, McLellan has his deconstruction technique down to a science. Incorporating his skill with a camera, the detail-oriented experimenter has turned what were once idle personal explorations into striking works of visual art.

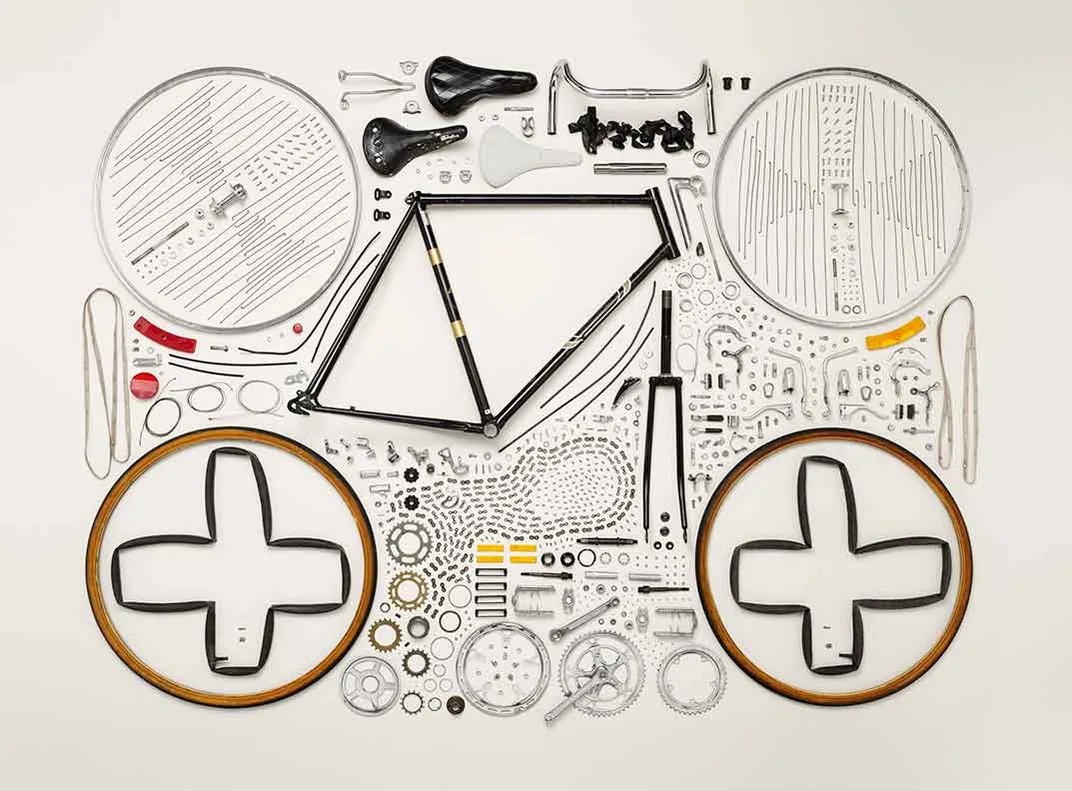

Drawing his inspiration from assembly diagrams of the sort found in user’s manuals, McLellan lays out his own “exploded views” using the physical components themselves, rather than two-dimensional digital facsimiles. In so doing, he eliminates abstraction from the equation, and presents viewers with the purest imaginable breakdowns of products they employ every day.

“I wanted to profile [them] in a way that was true to the object, that shows the mechanics,” McLellan says. “It’s quite amazing that the thing works, but then beyond that, how does it work? And how does it fit in one exterior shell?” His art attempts to answer these questions.

In his 2013 book Things Come Apart, McLellan presents dozens of richly colored images, each one captured from a bird’s-eye perspective, and each devoted to a particular appliance or gadget.

As the artist explains, arranging components in an intuitive, compelling way can be half the challenge. Part of his aim in crafting his schematic layouts is for viewers to be able to intuit the process by which the devices were broken down in the first place, i.e., to preserve to the extent possible the differentiation between the outermost, intermediate and innermost layers of parts.

McLellan is methodical in the extreme. “When I’m disassembling,” he says, “I understand: this is the core of the unit, so these pieces stay together, this is the top part of the unit, so those pieces stick,” and so on.

Having broken an object down into as many parts as possible using only rudimentary tools, McLellan orients the components in a way that strikes an elusive balance between technical rigor and visual appeal, then takes his photograph.

Looking at McLellan’s dazzling array of Smith-Corona typewriter components, 621 in all, one cannot help but be impressed, by the skill of both the artist and the machine’s original inventor. “When you start pulling it apart,” McLellan describes, “seeing the arms, and those three different levers. . . it’s quite amazing. The backwards engineering to that is unreal. It baffles me.”

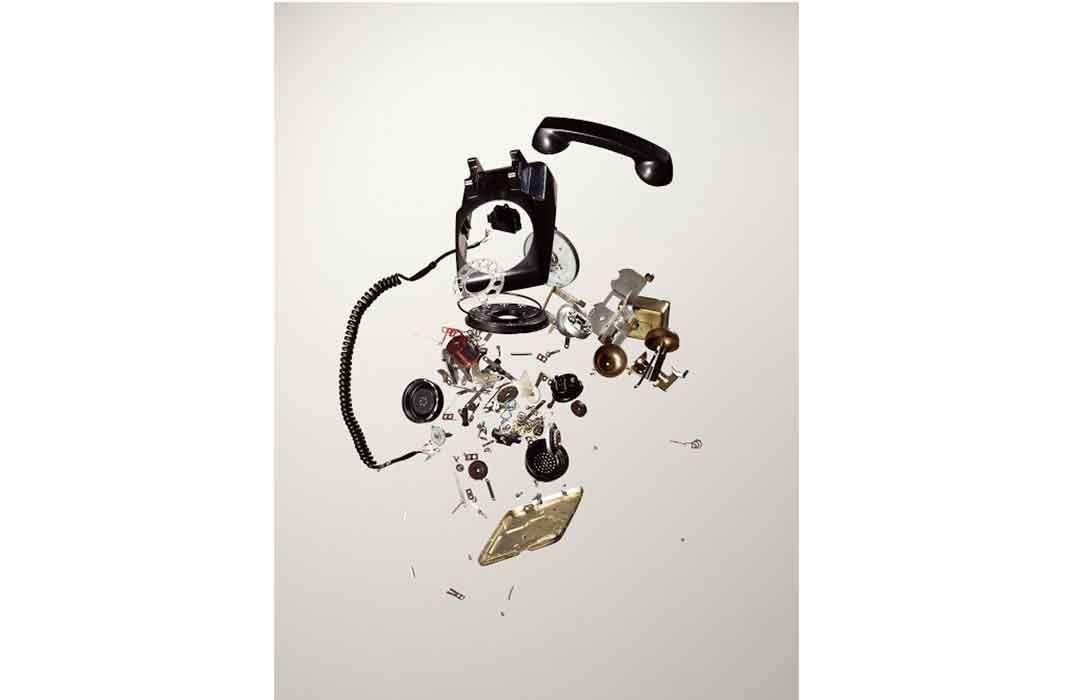

Lately, in addition to his static, overhead views of disassembled devices, McLellan has refined a more dynamic kind of photography: mid-free fall snapshots of deconstructed objects caught in gravity’s pull. He sees these motional, chaotic images as the perfect complement to his precise maps of components.

“I’m Gemini,” he explains, “so I have two personalities.”

To capture cascading mechanical parts, McLellan initially took a bare-bones approach, relying on little more than a ladder, tripwire and high-speed camera. These days, with his projects growing increasingly ambitious in terms of component count, McLellan’s method is somewhat more refined.

Now, he drops components subset by subset, envisioning beforehand the way each should fall through the air. Once he’s captured an image of one subset more or less in line with his imagining, he moves on to the next, bearing in mind all the while the results of the previous shoots. When all is said and done, he layers the images, so it appears to the viewer as though the whole object was dropped and captured in one go.

McLellan’s two distinct styles of photography are both well-represented in the travelling exhibition, whose appeal he hopes will be universal. In particular, though, the artist and his Smithsonian sponsors are looking to enthrall scientists in the making, kids who might spend their weekends breaking apart toy cars in the way McLellan once did.

To this end, each stop on the tour will feature Spark!Lab activities—interactive, hands-on opportunities for neophytes to more intimately engage with the material, and to utilize their own curiosity.

McLellan himself is looking forward to the show in a big way. “I’m excited to see it, and see the reception,” he tells me. “And I hope a lot of the young engineers get excited by it [too].”

"Things Come Apart," a traveling exhibiton circulated by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) begins its 12-city national tour at the Upcountry History Museum at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, where it is on view through February 19, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)