For These Native American Artists, the Material Is the Message

A new exhibition traces the evolution of Plains tribes’ narrative art from the 18th century up through today’s contemporary works

Material matters. That is one of the themes of “Unbound: Narrative Art of the Plains,” a new exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Gustav Heye Center in New York City. It explores the evolution of storytelling art among Plains tribes dating back to 18th century, while showcasing brand new works from artists working in this tradition today.

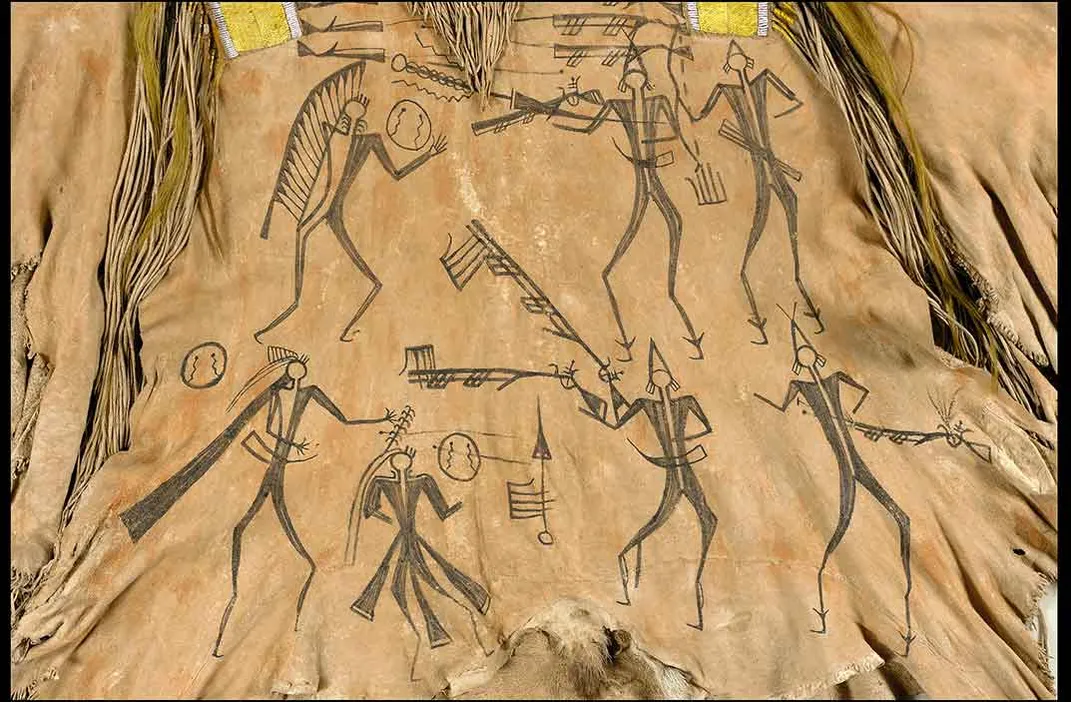

“The stories that they are telling are either war deeds, horse-raiding scenes, ceremonial scenes, or courting,” says the show’s curator Emil Her Many Horses (Oglala Lakota). “Usually they were rendered on clothing or robes or tipis, then later other materials were introduced: muslin, canvas, then ledger books.”

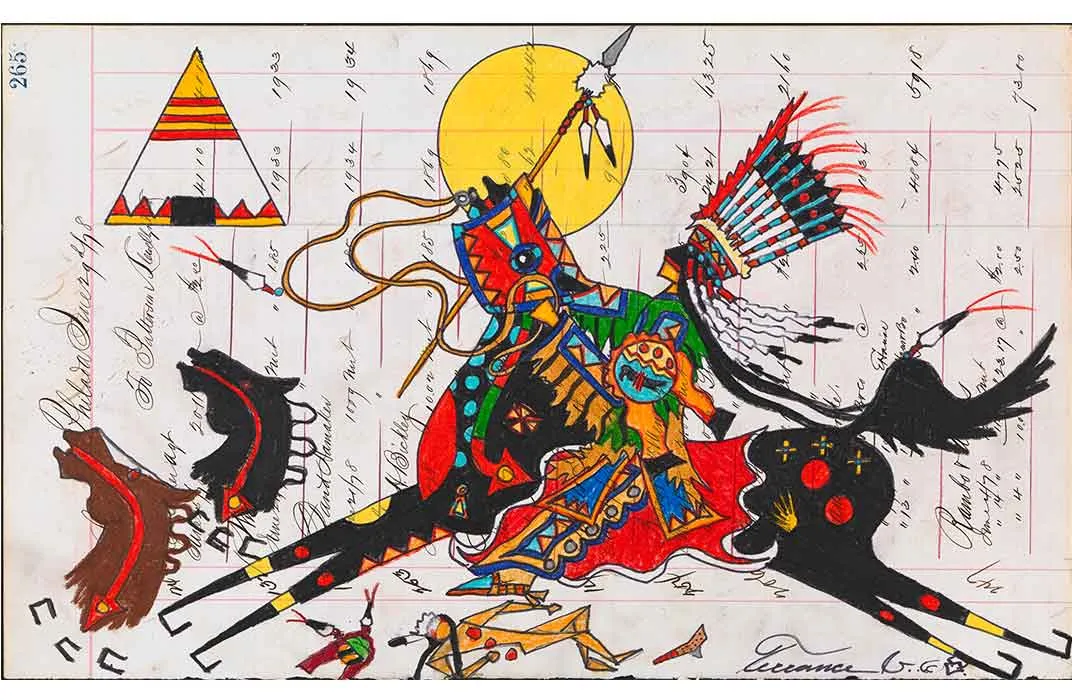

Plains artists began using ledger paper from surplus government accounting notebooks, or ledger books, which became widely available during the reservation era (1870–1920). As the U.S. government imposed policies aimed at assimilating Native Americans into the mainstream culture, and in many cases imprisoning the Plains Indians, the crafting of “ledger art” became a way for the warrior-artists to hold on to their heritage and document their experiences.

A prominent example of this took place at Fort Marion, in St. Augustine, Florida, where more than 70 southern Plains warriors were incarcerated by the military from 1875 to 1878. The difficulty of such circumstances and efforts of the government to impose a new set of values on the Native Americans pervades these works, such as an 1875 colored-pencil drawing by Southern Cheyenne artist Bear’s Heart, showing prisoners lined up being preached to by a bishop.

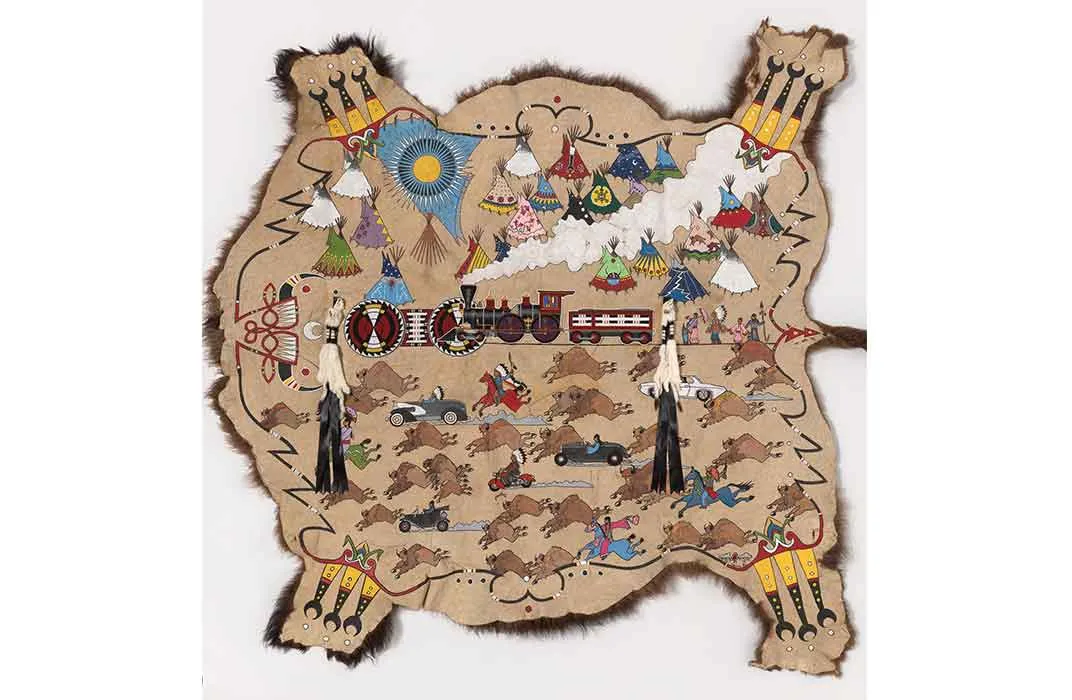

But as prevalent are depictions of glorious battles and traditional ceremonies—such as Crow artist Spotted Tail’s work on elk hide in which a warrior uses a lance to take down a gun-toting enemy; or Yanktonai medicine man No Heart’s painting on muslin of a mock battle and victory dance. Because the accounting books became such common materials on which to create art, the term “ledger art” has come to be interchangeable with “narrative art,” a fact the show’s curator sought to explore.

Plains narrative art started as early as the 1700s, with warrior-artists painting deerskin shirts or buffalo-hide tipis and robes, illustrated with records of their battles and horse raids. Some works recorded communal gatherings and powwows. Throughout the 19th century, as settlers and U.S. military officers moved onto the plains, their intrusion could be seen in the new materials used in the works—crayons, pencils and canvas.

“Unbound” includes examples from each of these eras, from paintings on elk hide in the 1880s to recent illustrations on graph paper with colored pencils. In each piece, the material on which the imagery is painted adds to the work itself, providing a lens into the artist and the environment in which it was created.

“The title, ‘Unbound,’ means that it’s more than paper,” says Her Many Horses. Indeed, the show explores how this art served as a form of release for Plains warriors who were in some cases, literally bound.

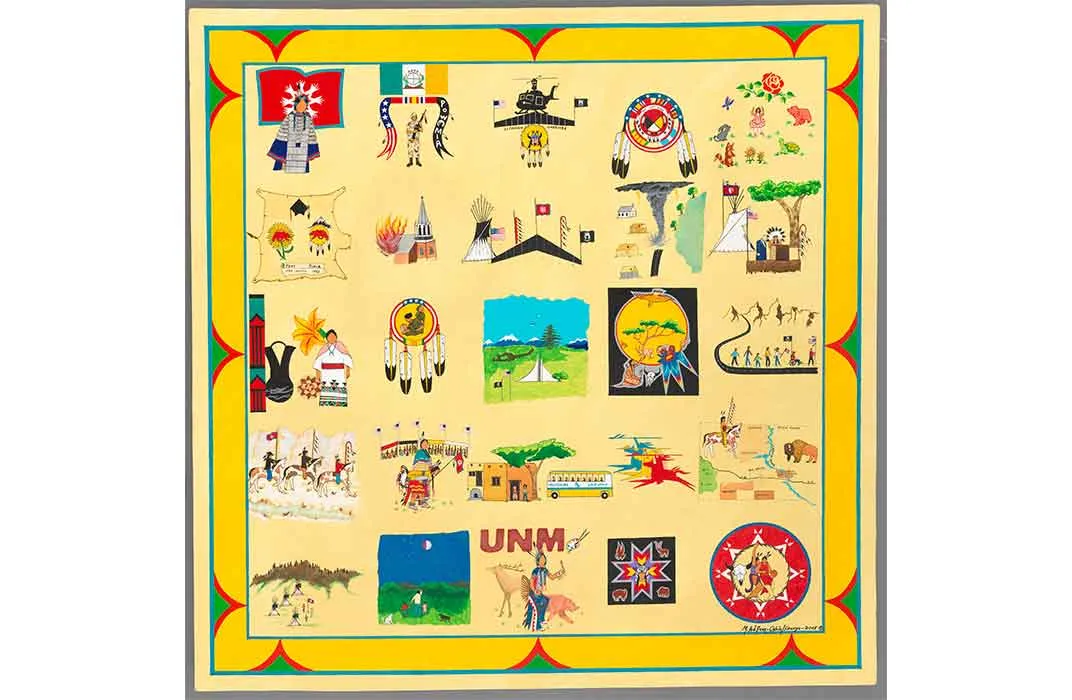

But in addition to the rich historical works included in “Unbound,” the show also includes more than 50 contemporary works of narrative arts, from current Plains artists, which Her Many Horses commissioned exclusively for the exhibition.

In commissioning the works, Her Many Horses sought to invite artists in tribes that had narrative art as part of their historic traditions—northern, central, and southern Plains groups. Her Many Horses is an artist himself, specializing in beadwork and quiltwork, and he attends a number of art markets, so he “really saw what was happening with narrative art,” and had a few artists in mind when he began to devise the exhibit.

“I literally went to these artists and said ‘I want five ledger drawings,’” he says. He then followed up with each artist asking: "what would you like to see in the collection of the Museum of the American Indian?

“I knew I didn’t just want one piece—I wanted a body of work from each artist.”

The resulting exhibition provides a diverse collection of subjects and tones. Her Many Horses gives the example of Oglala Lakota artist Dwayne Wilcox, whose works take on a lighter tone in scenes of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show of the 1800s, and a modern powwow in which people dressed in contemporary clothes join in the celebration—“healing through humor” as Her Many Horses puts it. Or the more realistic black-and-white pencil drawings of artist Chris Pappan.

“Some artists chose to do more traditional styles of drawings, others chose to do dance and contemporary warrior societies,” he says. “I really left it up to them to make that decision.”

Materials also varied, with the artists interpreting the direction to create “ledger drawings,” in a number of ways. For example, Pappan’s portrait of warrior Spotted Eagle was drawn on a 19th-century U.S. Army ledger book (“Knowing the history between our people and the U.S. Army, I see creating artwork on this paper as my form of counting coup,” the artist told Her Many Horses.)

Another of Pappan’s pieces uses paper on which a real-estate deal was recorded to illustrate a 19th-century Osage tribal delegation on their way to Washington, D.C. Graph paper, antique ledger paper, and paper cut to mimic a buffalo hide are among the other materials used by the artists.

“To some of them, ledger drawings meant the style, not the paper,” while to others, the paper carried deep meaning, says Her Many Horses. “Some artists might look for ledgers with specific associations with their tribe, or run across a book for ‘Blackfoot Agency.’”

The result is a collection of works that reflect how art can release materials from their original context, and infuse them with a whole new meaning. The narrative art tradition of Plains tribes has in this way given a new value to accounting books from decades, even centuries ago. Her Many Horses recalls going to an antique store with other ledger artists who specifically asked the seller if they had any ledger books. “The owner said ‘no, you’re the second person who asked today.’”

“Unbound: Narrative Art of the Plains” is on view through December 4, 2016 at the National Museum of the American Indian, George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. The museum is located at One Bowling Green, New York, New York.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/e5/01e52e8b-bb25-429e-ae26-81cee3510dde/2069841267003f7973844kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/fa/d3fac65a-db1c-4726-a213-6415da38628f/img1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/ef/64efdddc-61f3-4689-9122-28b730abb04c/img2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/ed/85ed2a24-8d58-4f84-a2d1-36315ad89317/2465384149515468c5049kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/47/6f47905a-355d-401f-9b88-359baab8de44/2402682317300602c5348kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/b1/a6b1ee73-b93f-4a55-a2a4-d10e97068f30/245716565215bd8003238kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/1b/e41bbcd5-40f9-4922-830c-e3f2844d324a/242861144292ee8a2d811oweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/17/731787ae-c8c0-48fd-92de-8897413feb3f/240257021244ef5982218kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/62/956237ab-e0e1-4996-9a8b-9ff033aacb72/24627639086e9642b829fkweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/db/66db94ac-2cd8-487e-a530-a52c7ae58842/24358300600fa96923ff7kweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)