The List: Medical Innovations at the Smithsonian

On the anniversary of the legendary discovery of polio, take a tour of the most significant medical inventions in history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110928114004penicillin-small.jpg)

On this day 83 years ago, one of the most unexpected medical breakthroughs in human history occurred: Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming woke up to discover a mold growing in one of his petri dishes. Looking closer, he realized that wherever the mold was growing, the staphylococci bacteria he was culturing had died. He spent the next decade growing the penicillium mold and trying to isolate the antibiotic it secreted. The substance—which he termed penicillin—would go on to become the world’s most important antibiotic, saving millions of lives starting in World War II.

The American History Museum is fortunate to be home to the original petri dish in which Fleming found the mold. To commemorate this remarkable discovery, The List this week is a compendium of artifacts held in the Smithsonian collections that represent some of the most significant medical breakthroughs in history.

1. Early X-ray Tube: In 1895, Wilhelm Roentgen, a German physicist, was experimenting with passing electrical currents through glass vacuum tubes when he noticed a strange green glow on a piece of cardboard that was lying on his workbench. He soon discovered that invisible, unknown “x” rays were passing out of the tubes, causing the phosphorescent barium he’d painted on the cardboard to glow. Within a few weeks, he’d used this newly discovered form of energy to take a picture of his wife’s hand bones, producing the first X-ray image in history.

2. Salk’s Polio Vaccine and Syringe: During the first half of the 20th century, polio was an unchecked disease that affected millions worldwide, with no known cure. Experimental trials with the live virus as a vaccine routinely infected children. In 1952, a young virologist at the University of Pittsburgh named Jonas Salk developed a vaccine using the killed virus; with few volunteers willing to be injected with it, his first human subjects included his wife, children and himself. Subsequent field trials showed his vaccine to be safe and effective, leading to the eradication of polio in the United States, a major milestone in battling infectious disease.

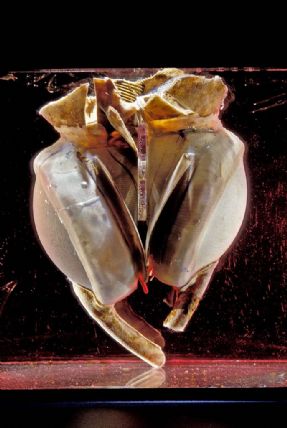

3. First Artificial Human Heart: Serious research into a mechanism for replacing the human heart started as early as 1949, and in several experiments, animal hearts were successfully replaced with artificial ones for short periods of time. But it wasn’t until April 4, 1969, when Haskell Karp lay dying of heart failure at a hospital in Houston, that doctors were able to successfully implant a mechanical heart into a human. This pneumatic pump created by Domingo Liotta was implanted by surgeon Denton Cooley, allowing the patient to live for 64 hours until a human heart transplant was available. Sadly, Karp died after receiving the transplant of a real heart due to a pulmonary infection.

4. First Whole-Body CT Scanner: Robert S. Ledley, a biophysicist and dentist, was an early proponent of using computer technology in biomedical research, publishing articles on the topic as early as 1959. After using computers to analyze chromosomes and sequence proteins, he turned to body imaging. His 1973 ACTA scanner was the first machine to use CT (computer tomography) technology to scan the whole body at once, compiling individual x-ray images to create a composite picture of the body, including soft tissue and organs as well as bones.

5. Recombinant DNA Research: Today, genetic modification is involved in everything from manufacturing insulin to producing herbicide-resistant crops. Research by Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer between 1972 and 1974 showing that genes from one type of bacteria could be transferred to another paved the way for these future advances in manipulating the genome. Cohen’s handwritten notes on page 51 of this notebook, titled “Outline for Recombination Paper,” provide an early view into this groundbreaking discovery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)