The Director of the Indian Museum Says It’s Time to Retire the Indian Motif in Sports

Are teams like the Indians, the Braves and the Redskins reflecting racial stereotypes?

The Washington football team is a notable example of groups that still use Indian names or imagery for mascots. Photo by Ryan R. Reed

When Kevin Gover was a kid growing up in Norman, Oklahoma, college students at the nearby University of Oklahoma had begun protesting the school’s mascot. Known as “Little Red,” the mascot was a student costumed in a war bonnet and breech cloth who would dance to rally crowds. Gover, who today is the director of the American Indian Museum, says he remembers thinking, “I couldn’t quite understand why an Indian would get up and dance when the Sooners scored a touchdown.” Of Pawnee heritage, Gover says he understands now that the use of Indian names and imagery for mascots is more than just incongruous. “I’ve since realized that it’s a much more loaded proposition.”

On February 7, joined by a panel of ten scholars and authors, Gover will deliver opening remarks for a discussion on the history and ongoing use in sports today of Indian mascots.

Though many have been retired, including Oklahoma’s Little Red in 1972, notable examples—baseball’s Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves, and football’s Washington Redskins—continue, perhaps not as mascots, but in naming conventions and the use of Indian motifs in logos.

“We need to bring out the history, and that’s the point of the seminar, is that it’s not a benign sort of undertaking,” explains Gover. He’s quick to add that he doesn’t regard the teams’ fans as culpable, but he likewise doesn’t hesitate to call out the mascots and the names of the teams as inherently racist.

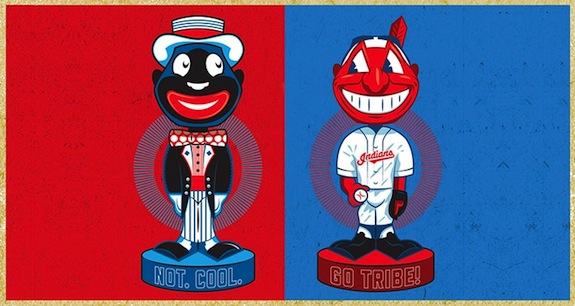

Black and American Indian caricatures were both popular in the past, but Gover says American Indian mascots continue to linger in the modern sports scene. Illustration by Aaron Sechrist,

courtesy of the American Indian Museum

Many of the mascots were first employed during the early 20th century, a time when Indians were being oppressed under policies of Americanization. Children were forced into boarding schools. Spiritual leaders could be jailed for continuing to practice native religions.”It was a time when federal policy was to see that Indians disappeared,” says Gover. Looking back on the timing of the mascots’ introduction, Gover says, “To me, it looks now as an assertion that they succeeded in getting rid of the Indians, so now it’s okay to have these pretend Indians.”

A push for Native American equality and tribal sovereignty emerged during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. “That’s when the response started,” says Gover. “There’s a lot of activism around it. Since that time, slowly but surely, a lot of the mascots have been done away with.”

Gover made an effort to get a range of expertise on the panel but significantly, he says he was unable to find anyone willing to defend the continued use of the mascots. That doesn’t mean those people don’t exist, says Gover. At some of the very schools which banned racist mascots, alumni are calling for a return to the old ways. “I actually saw a website a couple of weeks ago where a lot of Stanford alum were wearing this clothing that had the old symbol on it,” Gover says.

But he still believes that momentum is on his side. “The mood is changing,” Gover says, “and I have no doubt that in a decade or two, these mascots will all be gone.”

The discussion “Racial Stereotypes and Cultural Appropriation” will be held at the American Indian Museum, February 7, 10:00 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. Get the live webcast here. Panelists include:

- Manley A. Begay Jr. (Navajo), moderator, associate social scientist/senior lecturer, American Indian Studies Program, University of Arizona, and co-director, Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

- Lee Hester, associate professor and director of American Indian Studies and director of the Meredith Indigenous Humanities Center, The University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma

- E. Newton Jackson, associate provost and professor of Sports Management, University of North Florida

- N. Bruce Duthu (United Houma Nation of Louisiana), chair and professor, Native American Studies, Dartmouth College

- Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne/ Hodulgee Muscogee), moderator. President, Morning Star Institute and past executive director, National Congress of American Indians, and a founding trustee of the National Museum of the American Indian

- C. Richard King, co-editor, Team Spirits, Native Athletes in Sport and Society, and Encyclopedia of Native Americans in Sports, and professor and chair of the Department of Critical Gender and Race Studies, Washington State University

- Ben Nighthorse Campbell, Council of Chiefs, Northern Cheyenne Tribe; President, Nighthorse Consultants; Trustee, National Museum of the American Indian; Award-winning Artist/Jeweler, U.S. Representative of Colorado (1987-1993); and U.S. Senator of Colorado (1992-2005)

- Delise O’Meally, director of Governance and International Affairs, NCAA

- Lois J. Risling (Hoopa/Yurok/Karuk), educator and land specialist for the Hoopa Valley Tribes, and retired director, Center for Indian Community Development, Humboldt State University

- Ellen Staurowsky, professor, Department of Sports Management, Goodwin School of Professional Studies, Drexel University

- Linda M. Waggoner, author, Fire Light: The Life of Angel De Cora, Winnebago Artist; and “Playing Indian, Dreaming Indian: The Trial of William ‘Lone Star’ Dietz” (Montana: The History Magazine, Spring 2013), and lecturer, Multicultural Studies, Sonoma State University

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)