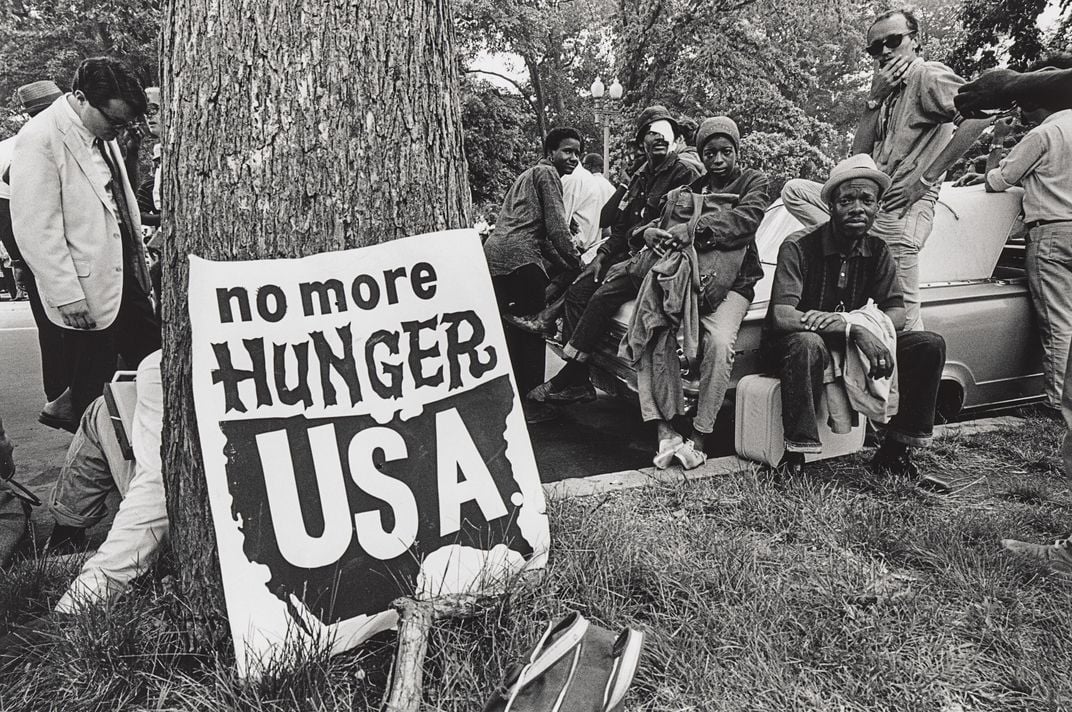

"I came here with the campaign to tell people that we got to be treated like human beings,” said Henrietta Franklin, a poor black woman from Mississippi, explaining to the Washington Post what had brought her to Resurrection City in Washington, D.C. in the spring of 1968. That past winter, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had revealed plans to erect a mini-metropolis on the National Mall as part of King’s Poor People’s Campaign. The encampment would send a message that the War on Poverty was far from over. Even after King was assassinated that April, his supporters forged ahead.

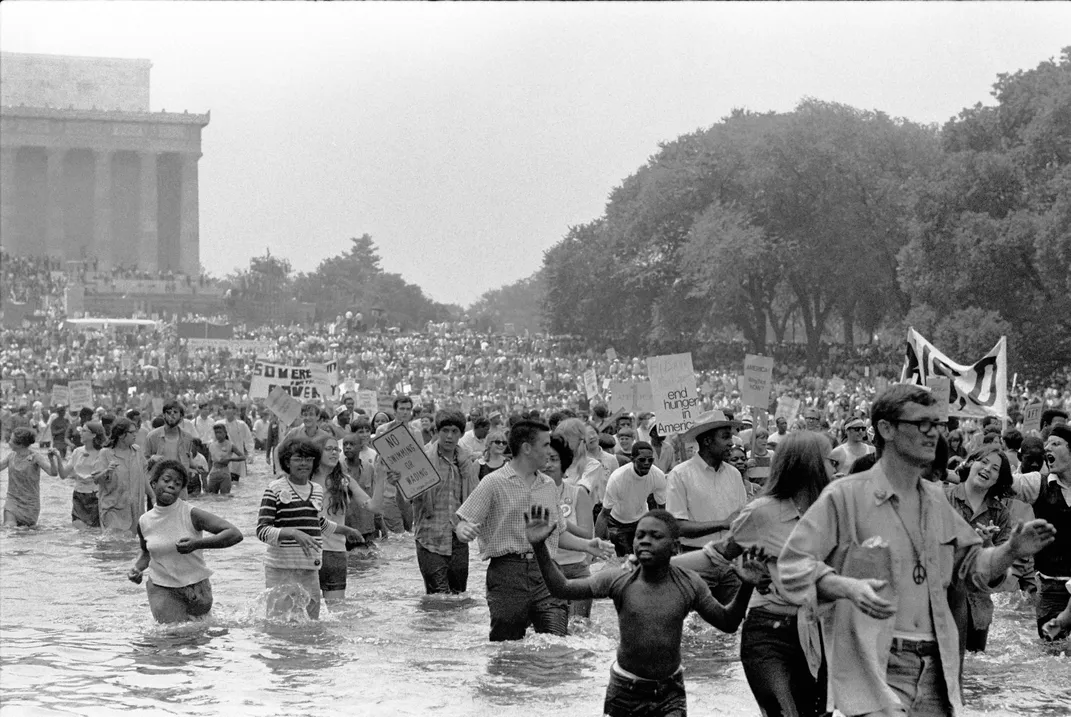

The first demonstrators arrived in May. In a matter of days, they built the roughly 16-acre encampment of tents—reminiscent of the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression—and for six weeks, at least 2,500 poor Americans and anti-poverty activists took over real estate near the Reflecting Pool. Resurrection City even had a ZIP code: 20013.

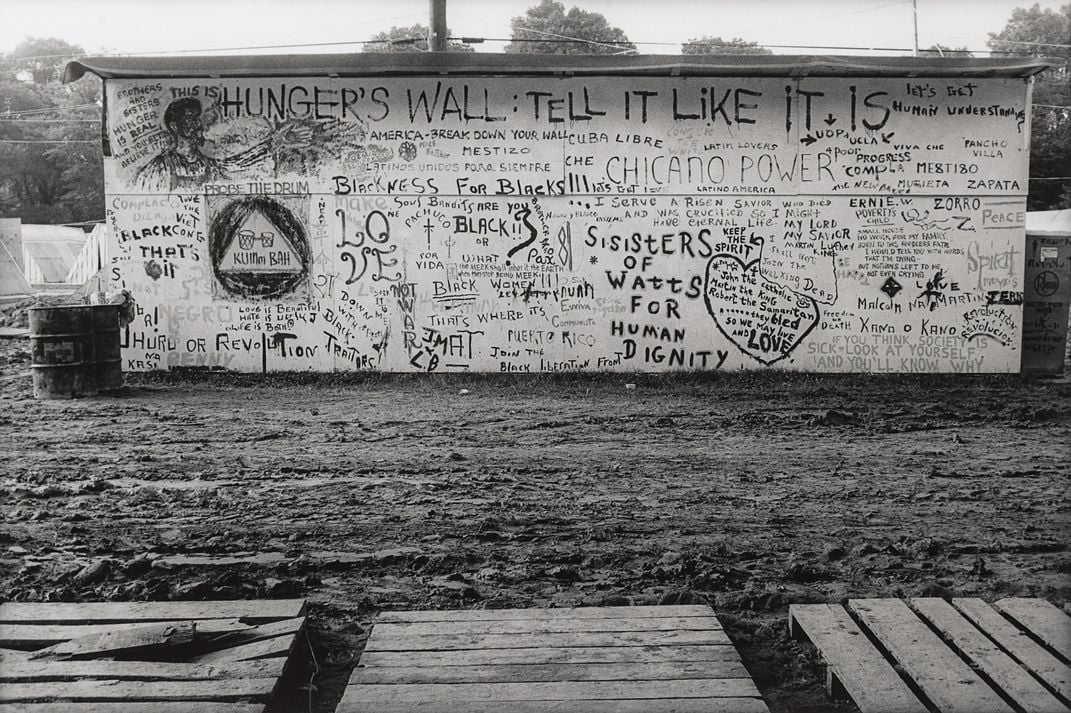

Perhaps the shantytown’s most memorable structure was the Hunger Wall, which served as a backdrop for the encampment’s city hall. The wall gave protesters space to write words that evoked both the movement’s unity and its notable diversity. Black Americans made up the majority of the Resurrection City population, but there were contingents of Native Americans, Latinos and poor white Americans, too. The Hunger Wall’s art is the work of a broad coalition of activists who, while they had varying ideas for achieving change, shared a sweeping ambition: securing economic justice for people long denied it.

Explore the Meaning Behind the Mural’s Words and Drawings

Curator Aaron Bryant of the National Museum of African American History and Culture takes you through the wall’s iconography. In the two interactives below, representing the left and right halves of the mural, click on the numbers to learn more.

—Text by Nora McGreevy

(If viewing this using Apple News, click here to see the first half of the interactive mural and here to see the second set of panels.)

One prominent figure at the encampment was Reies Tijerina, known for helping to bring the Chicano civil rights movement to national attention. Tijerina had led a Chicano group from New Mexico, while Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales did the same for Chicanos from Colorado, and Alicia Escalante and Bert Corona organized California groups. Each group advocated for its own slate of policies. George Crow Flies High, chief of the Hidatsa Tribe of North Dakota and one of Resurrection City’s Native leaders, helped arrange a march to the Supreme Court to protest a ruling that limited Native fishing. SCLC President Ralph Abernathy made appeals for a federal jobs program, while Chicano leaders set their sights on other solutions to poverty, such as protecting land rights for Mexican Americans.

At the time, the press largely considered Resurrection City to be a failure, as the journalist Calvin Trillin noted with irony: “The poor in Resurrection City have come to Washington to show that the poor in America are sick, dirty, disorganized and powerless—and they are criticized daily for being sick, dirty, disorganized and powerless.” Public reaction, too, seemed to dwell on the internal tensions and general appearance of squalor and disorder—persistent rain and poor drainage caused flooding. In retrospect, though, such a narrow focus missed what made the effort so remarkable. At a moment of profound national reckoning, just a few years after the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act were signed into law, activists at Resurrection City brought unprecedented visibility to the scope of American poverty.

The encampment’s remarkable diversity was a tribute to King, who “always exhibited a sensitivity to the needs of Mexicanos,” Chicano leader Bert Corona recalled in his 1994 autobiography. “He understood our particular historical conditions, but he also stressed that we needed to struggle together to correct common abuses.”

On June 24, the day after Resurrection City’s permit expired, District Police arrested the remaining demonstrators, and bulldozers destroyed the encampment. But its legacy continues to energize protests to this day. This past June, activists followed Covid-19 restrictions on public gatherings and staged a virtual Poor People’s Campaign, with religious leaders and activists assembling via livestream to protest persistent inequality. More than 2.5 million people tuned in on Facebook. In a letter to policy makers, the organizers wrote: “We have been investing in punishing the poor; we must now invest in the welfare of all.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/0d/d10d734b-adaf-4c15-8fdb-ed4195663abd/mobile_-_sep2020_i01_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/58/2858b3e9-6dd2-420e-b827-b4acada7270a/opener_-_sep2020_i01_prologue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)