The Storied, International Folk History of Beauty and The Beast

Tales about a bride and her animal groom have circulated orally for centuries in Africa, Europe, India and Central Asia

:focal(567x158:568x159)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/68/1c688d77-f1e2-4422-9653-360c63f89aeb/batbphotography10web.jpg)

Beauty and the Beast are words that go together like coffee and cream, mice and men, sticks and stones, and vim and vigor. One explanation may be the alliteration, but I think a more compelling reason is that beauty and beast conjure images of stark contrast: one that is sublimely appealing in both mind and body and one that is animal-like and not in a soft, cuddly way. When the words are combined, the results may be both unexpected and provocative.

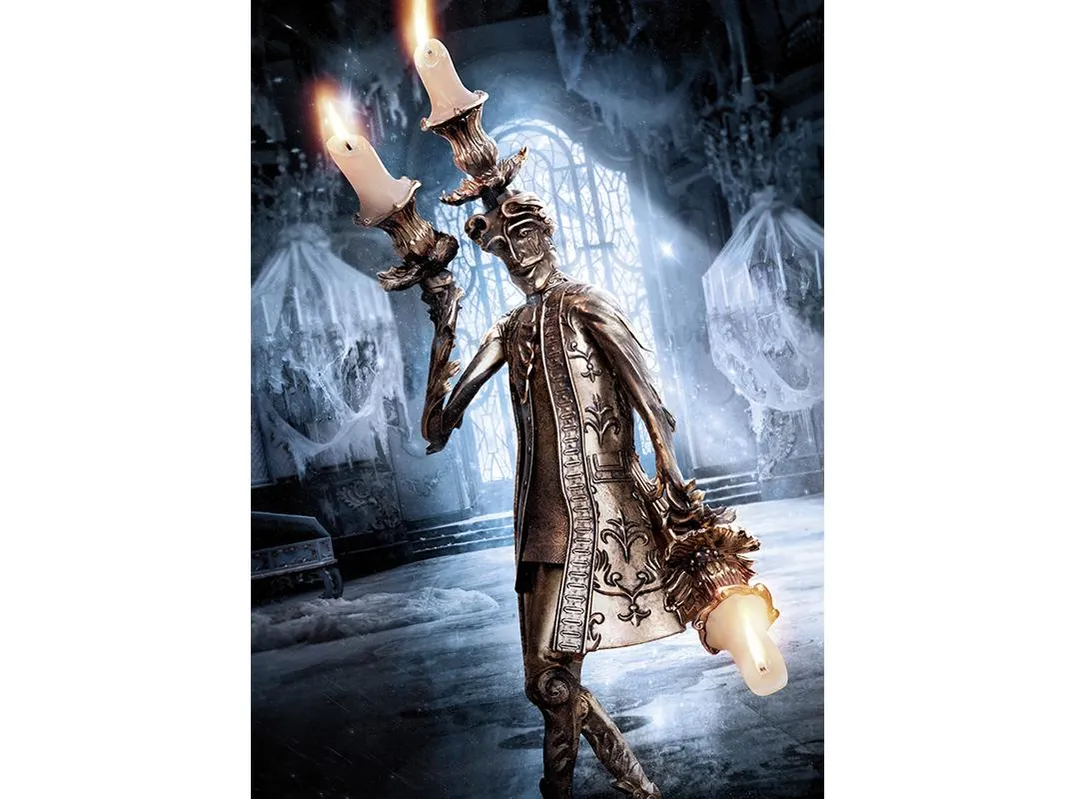

We’ll be hearing those words more frequently now that Walt Disney Pictures is poised to release a live-action version of Beauty and the Beast. The company hopes to capitalize on the success achieved in 1991 by its animated version, in the same way that its recent live-action versions of Maleficent (2014), Cinderella (2015), and The Jungle Book (2016) capitalized on the popularity of the Disney animated films that came before. (Maleficent is an alternative telling of the story of Sleeping Beauty)

Moreover, according to Time magazine, we can expect to see more live-action remakes of Disney classics in the years ahead: Mulan, Aladdin, The Lion King, Pinocchio, Dumbo, and Peter Pan.

Beauty and the Beast also has the advantage of deep roots in both folklore and popular culture. Traditional tales of a bride and her animal groom have circulated orally for centuries in Africa, Asia, Europe and India—stories that may have underscored the vital connection between human beings and the natural world.

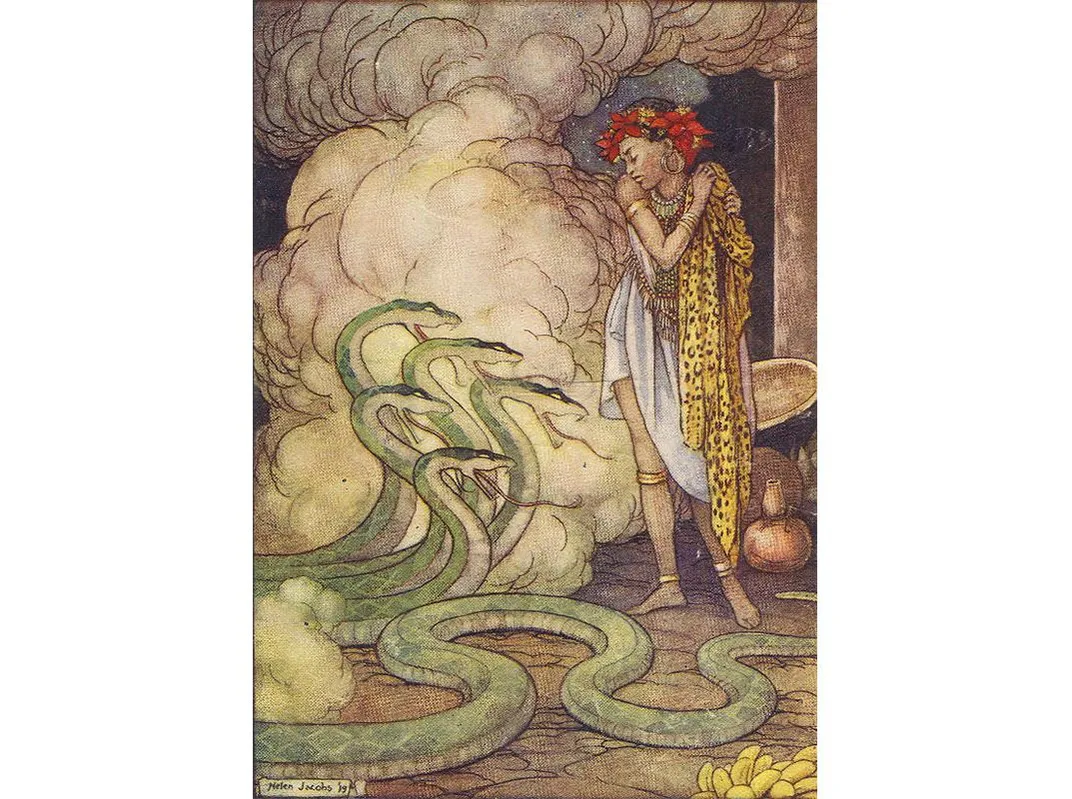

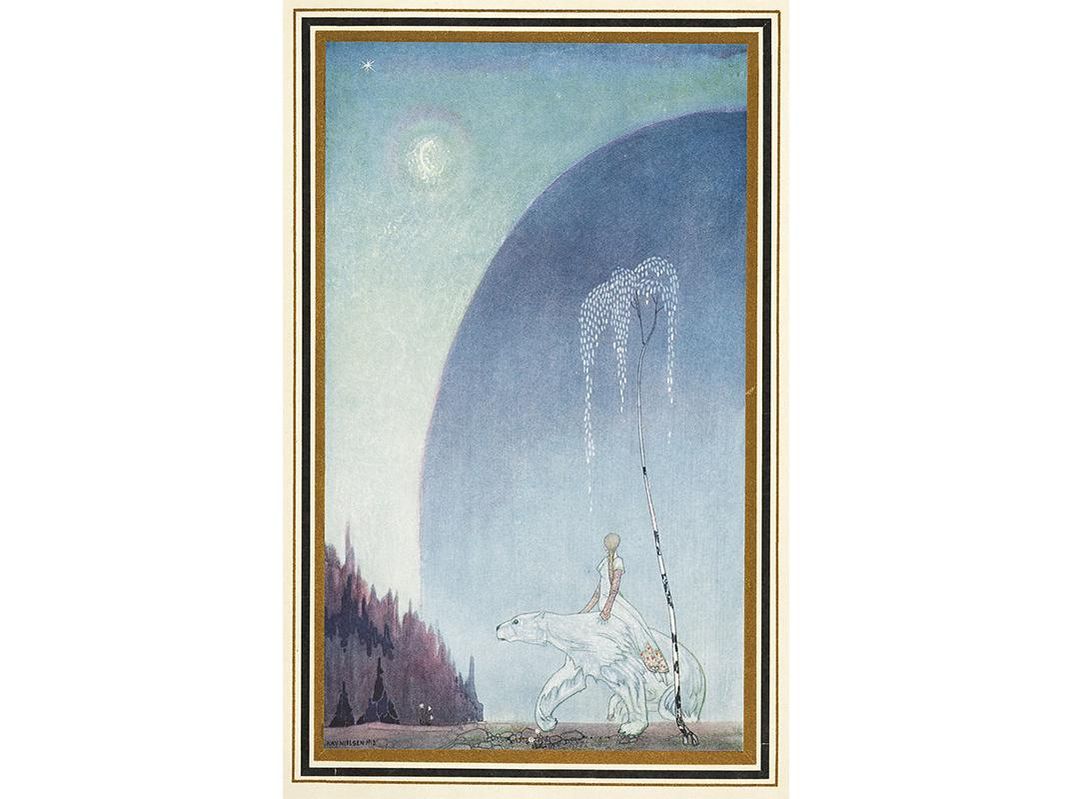

For instance, a folktale from southern Africa, “The Snake with Five Heads,” tells how the younger and more humble of two daughters marries a multi-headed serpent. In the Norwegian story “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” a white bear takes a human bride. And in the Chinese folktale “The Fairy Serpent,” a snake marries the youngest of three daughters. In each case, the animal groom is transformed into a handsome man.

The first appearance of “Beauty and the Beast” in print—in French, as “La Belle et La Bête”—was in 1740, as one of the tales in the book, La Jeune Américaine, et les Contes Marins, or The Young American and Tales of the Sea, by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Gallon de Villeneuve.

Sixteen years later, Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont cut some of Villeneuve’s sub-plots and published an abridged version (likewise in French) as part of Magasin des Enfants, which was translated into English and appeared in London as “Beauty and the Beast,” as part of The Young Misses Magazine in 1757.

Beaumont’s version became the standard telling of the tale, which found its way throughout the 19th century into numerous collections, often with elaborate illustrations, as well as in stage productions across Europe and the United States.

In some ways, the moral lessons of the story of “Beauty and the Beast” are the same as those found in many other folktales: virtue and hard work are rewarded; prodigal pride is punished; and marriage lasts happily ever after.

But there are also other lessons—several of which have become proverbial—that derive particularly from “Beauty and the Beast”: beauty is not skin deep; beauty is in the eye of the beholder; love is stronger than death; and believing is seeing—a corrective to “seeing is believing”—indicating that beliefs may be more powerful than what our eyes behold.

By November 1907, the phrase “beauty and the beast” was so well known that a headline in the Los Angeles Times used the phrase in jest. Rumormongers whispered the phrase in response to the scandalous trial of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle for the murder of Virginia Rappé, which ended in Arbuckle’s acquittal in 1922. And a play on the phrase appeared as the final line in the film King Kong (1933), when the showman Carl Denham observes, “It wasn’t the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast”—a line that was repeated word for word in the 2005 remake.

In spite of popular culture’s long fascination with the tale, the first film version did not appear until 1946: La Belle et la Bête, directed by the French poet and surrealist, Jean Cocteau. The stunning cinematography of Henri Alekan, the musical score of Georges Auric, the technical skills of René Clement, and even costumes designed by a 23-year-old Pierre Cardin, all combined to make what is regarded as “one of the most magical of all films,” in the words of critic Roger Ebert, and ranked at number 26 in world cinema by the British film magazine Empire.

It took five hours of makeup each day to transform Jean Marais into the Beast, and when the Beast is transformed in reverse into the Prince at the end of the film, Greta Garbo (or possibly Marlene Dietrich or Tallulah Bankhead, according to other accounts) is supposed to have cried out, “Give me back my beast.” Although never sexually explicit, La Belle et la Bête is charged with sexual undercurrents—enhanced by the relationship between Cocteau and Marais, who some believe were “the first modern gay couple.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, the 2017 live-action version of Beauty and the Beast will feature what is reported to be the first openly gay character in any Disney film: Josh Gad playing Gaston’s sidekick, LeFou—a move that already has sparked three backlashes: one from gay activists who feel that the character promotes negative stereotypes—LeFou, after all, means “the madman”; a second from social conservatives who maintain that gay characters make them feel uncomfortable; and a third from officials of the Russian government, who could ban the film if they decide that it contains elements of “gay propaganda.”

Varying interpretations of “Beauty and the Beast” have helped keep the story alive for centuries, presenting fresh versions for new generations. Each new version has the power to enthrall, to excite, or to provoke new reactions, as we shall soon see with the story’s latest incarnation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/dc/75dc27e4-0646-4d95-9855-3279bcf1b6c3/batbphotography11web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)