Space Exploration Would Be Nothing If We Didn’t Know How to Spacewalk

The Air and Space Museum brings the privileged experience to the public in an exhibit that chronicles 50 years of technology

While the “Space Age” may have included some of the most landmark cosmic milestones of the past century, leaving the space ship has always been the true goal. Walks on the moon marked the first of many instances of Extra-Vehicular Activity, or EVA, the term used for any travel in space outside a ship. At the National Air and Space Museum’s exhibition, “Outside the Spacecraft: 50 Years of Extra-Vehicular Activity,” an eye-catching display of 26 hand-sewn gloves reflects not only how astronaut gear has evolved over the past five decades, but more broadly, on the ongoing reinvention of space exploration.

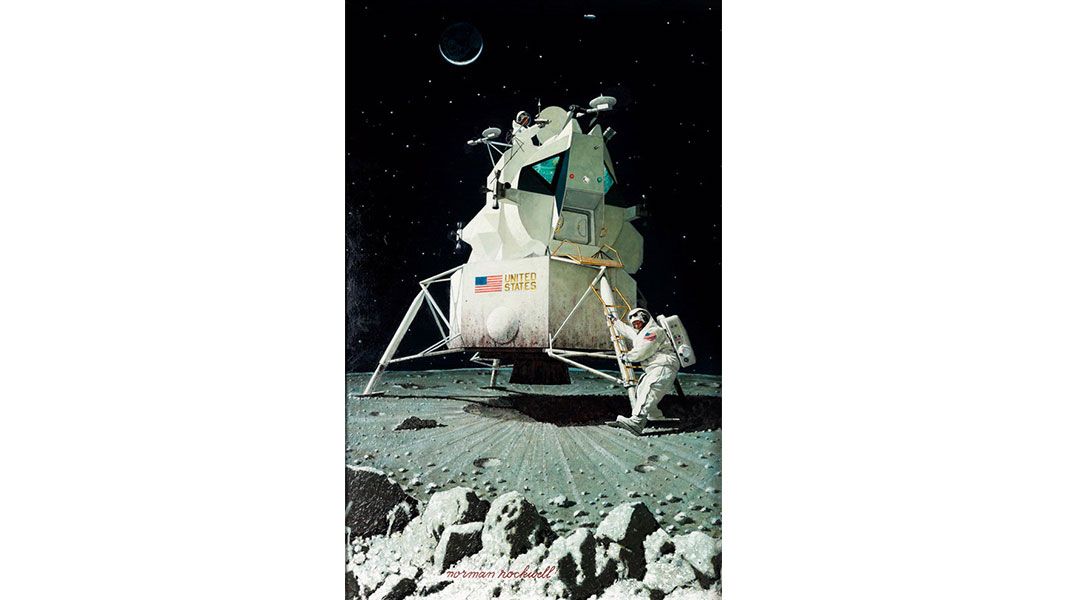

Art, tools and photography, including moon boots, space suits and even works by the much-loved populist illustrator Norman Rockwell tell the story, with artifacts dating from the first spacewalks by Soviet cosmonaut Aleksei Leonov and American astronaut Edward White in 1965.

“This, what’s shown here, is what formed the foundation for more space travel that has yet to happen,” says astronaut John Grunsfeld, a veteran of eight spacewalks, and an associate administrator for the science mission directorate at NASA. “Doing spacewalks is really an amazing thing to do,” he says, “but we’re still just at the start.”

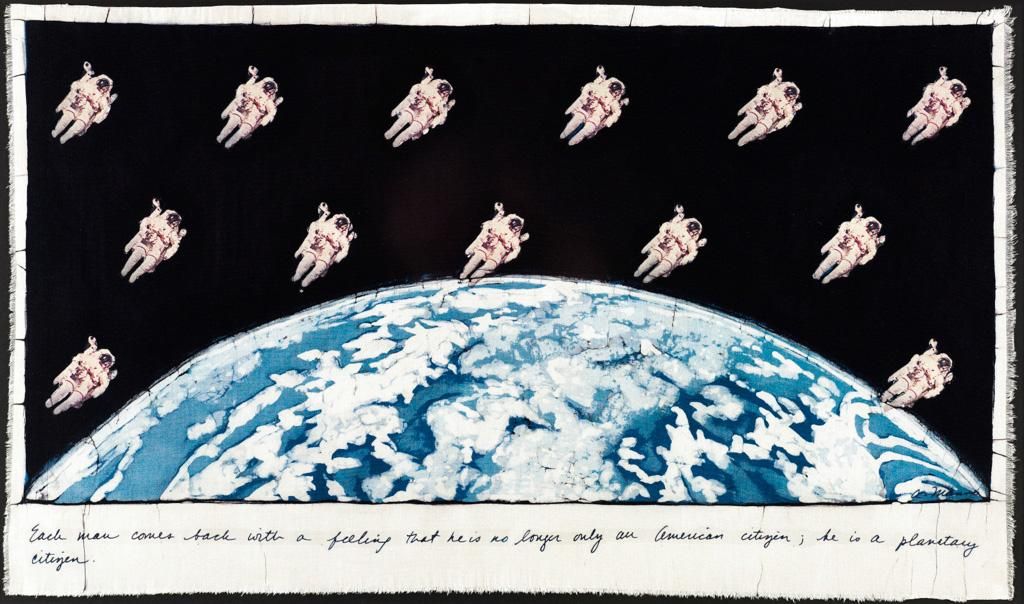

To date, 211 individuals have had the privilege of doing a spacewalk. Some of these excursions have taken place during several Apollo missions to the moon and shuttle trips to painstakingly repair the Hubble Space Telescope and construct and maintain the International Space Station.

“We landed on the moon to do spacewalks,” says Grunsfeld, “not to land on the moon in a can.” In order for more people to envision what it’s actually like to have this physical and mental experience, something Grunsfeld calls “the most natural and unnatural thing a human being can do,” curator Jennifer Levasseur strove to recreate an experience.

“We wanted to give visitors an intimate view of what it feels like to be in space, with graphic photos and incredible proximity to artifacts, so you can get as close as possible,” she says. The center of the exhibition has a floor-to-ceiling “selfie” wall depicting a high-resolution panorama of the moon’s surface to scale, where visitors can snap a “wish you were here” photo.

Close-up artifacts include delicately preserved space suits, what the exhibit terms the “personal spacecraft,” from missions including Gemini IX-A and Apollo 17, demonstrating how these items have changed over time to better accommodate pressure constraints in space as well as temperature shocks inside suits. In the first spacewalk, Leonov’s suit nearly killed him as it unexpectedly ballooned during the excursion. Later on, during a 1966 Earth orbital mission, fog clouded Gene Cernan’s visor because his suit wasn’t cooling properly. Mastering both these malfunctions have been key for developing the suit and insuring the safety of astronauts in later missions. Astronauts now have a rotary knob that controls the internal temperature of their suits, a uniform that has to withstand everything from -200°F to +200°F spikes.

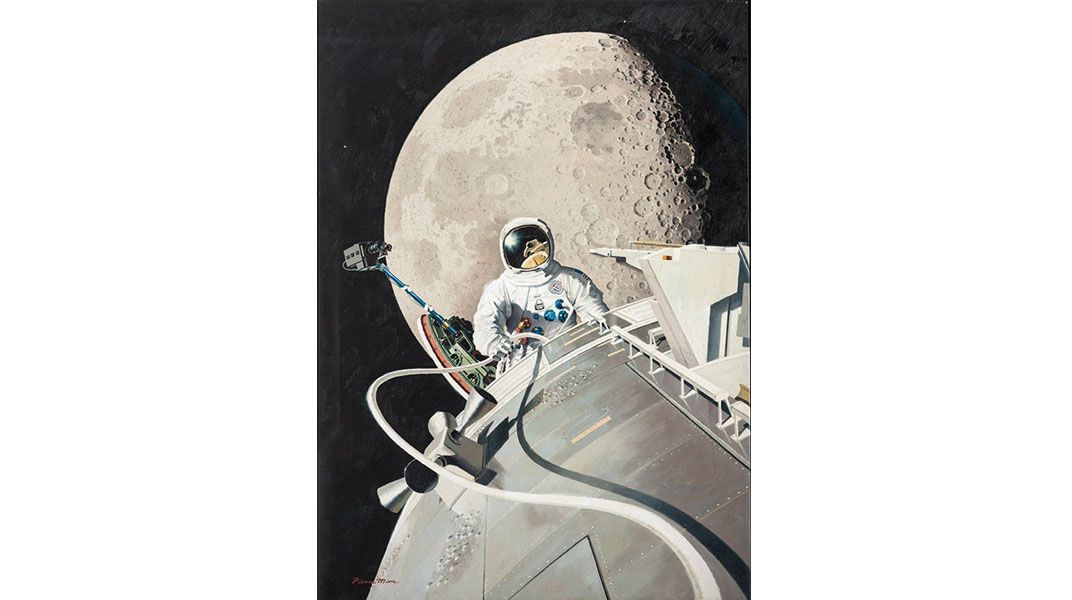

Crisp, enveloping visuals of space are also on display, as well as some of the progressively less bulky cameras that captured them, another physical embodiment of how much space travel and the tools used during trips have changed.

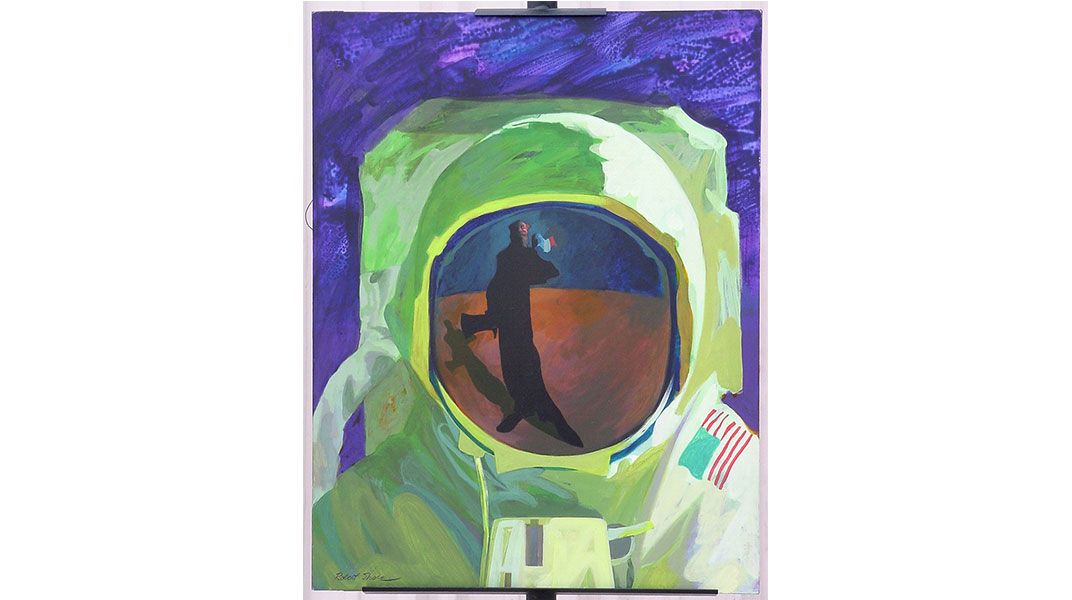

These images ask viewers to picture themselves dangling and floating with nothing but the Earth looming in the background. A photo of Grunsfeld from a Hubble servicing mission shows his distorted reflection in the metal of the space telescope, capturing the sensation of looking into a mirror while hovering above Earth. In 2014, astronauts installed the latest in high-definition cameras to the International Space Station.

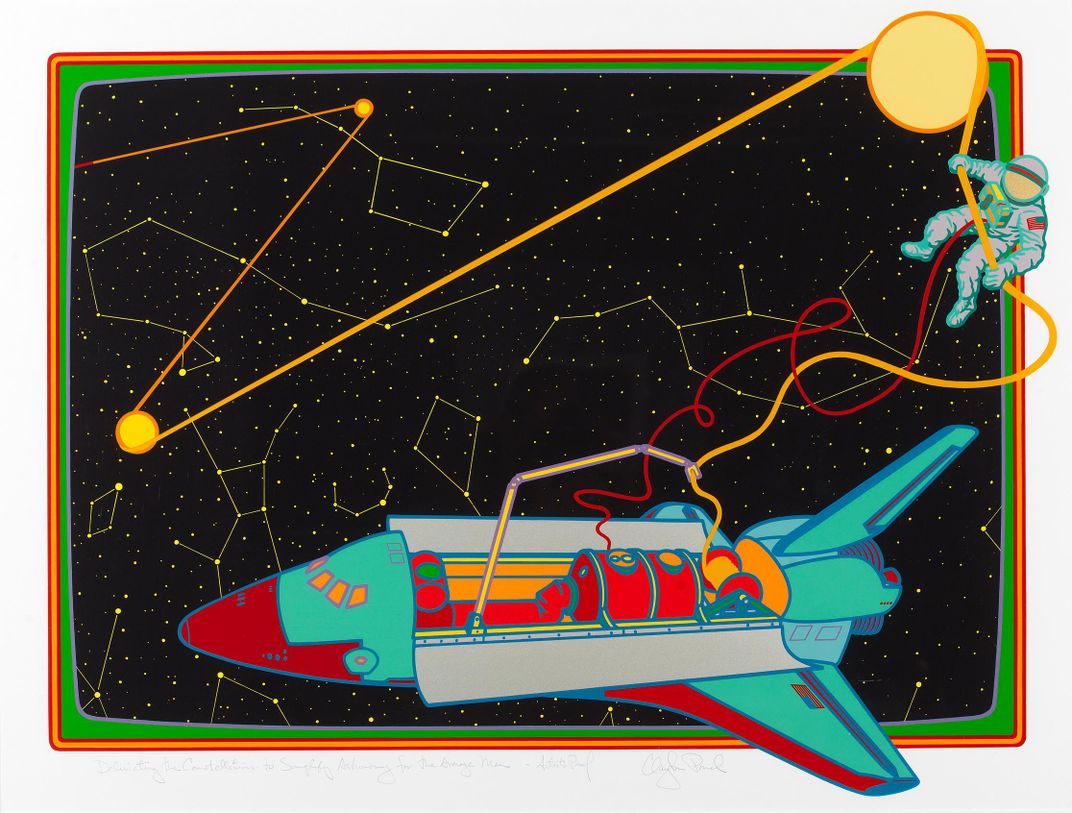

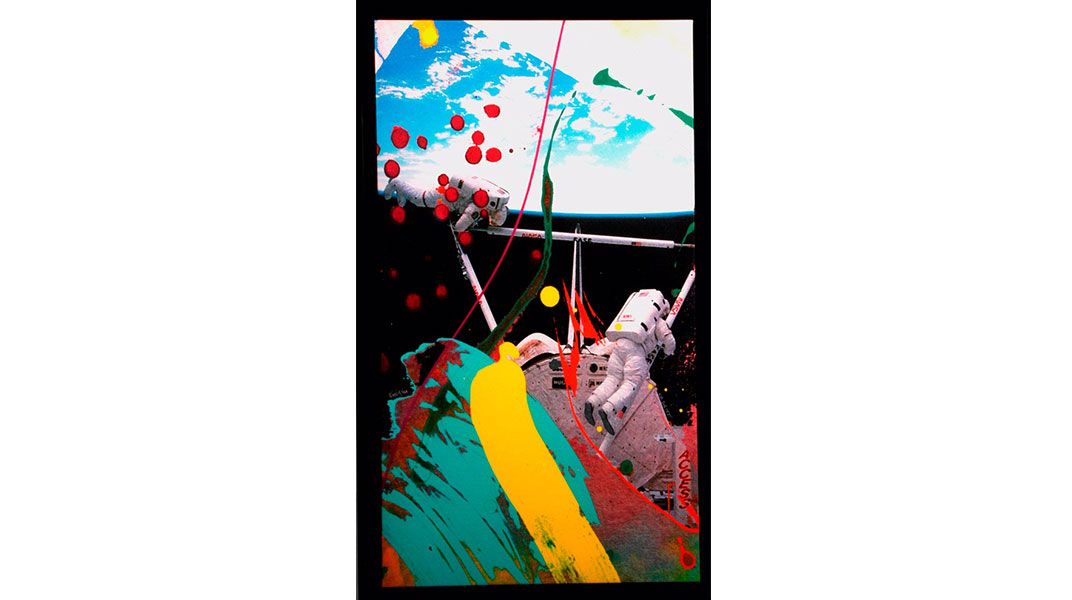

Juxtaposed against these artifacts and photography are splashy pop art paintings by Robert Shore, Michael Knigin and Clayton Pond. Offering another dimension of perspective, their art provides creative interpretations of what the space experience entails. “We get to see images of astronauts from their side of things and our side of things—both the real and imagined,” says Levasseur. Cernan has said images and art are one of the key channels that enable him to express what he encountered in space.

Such paintings also help bring visitors mentally closer to a distant setting. “Art, because it’s interpretive, is a very human way to understand something that has not been experienced,” says Levasseur. “It can often tell a bigger story, an easier story, than even a photograph.” (Astronaut Al Worden recently recalled a lingering disappointment to not have a camera with him to take pictures of his experience; but he later worked with an artist to recreate the moment he walked in space.)

This confluence of the colorful and bold “imagined” with the scientific serenity of space serves to illustrate the spectrum of thought and feeling that emerge during EVA. Visitors can get into the nitty-gritty of tools used on expeditions while simultaneously experiencing the mind-bending sensation of life suspended in weightlessness.

In uniting these two elements, the exhibition shows how spacewalks are both technical and emotional experiences. “Looking at the Earth for the first time, there is an incredible sense of wonder and awe,” says Grunsfeld. Yet, for him, the key differences of being out in space and suited up came down to “a million little things” like the ability to peel Velcro, scratch his nose, and reach beyond an arm’s length. In the grand arena of space, it was the small details that reminded him he was somewhere other than his garage, another place he often tinkered with inventions.

Space, says Grunsfeld, also provides a fresh perspective on our own planet. “I never saw a place on Earth where you couldn’t see the impact of humans, from ship wakes to deforestation. We are significantly changing the planet,” he says.

“Outside the Spacecraft: 50 Years of Extra-Vehicular Activity,” is on view through June 8, 2015 at the National Air and Space Museum, and commemorates the 50th anniversary of astronauts’ first landing on the moon. The museum’s 360° immersion continues online with a visually captivating website and Tumblr.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)