This Souped-Up Scuba Suit Made a Stratospheric Leap

The record-breaking Alan Eustace found just the right fit for his 25-mile free fall by marrying scuba technology with a space suit

:focal(745x444:746x445)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/b4/93b423c6-deea-4c7e-af72-98fe5e4093ce/alaneustacecase01701hor.jpg)

Former Google executive Alan Eustace calls himself a technologist. But he’s also the daredevil who parachuted from a balloon in the stratosphere more than 25 miles above the Earth in October 2014, breaking the world record for the highest free-fall parachute jump set by Felix Baumgartner in 2012.

“It was pretty exciting! We had already made five airplane jumps and that was the third balloon jump . . . in some ways it was the most relaxing of all of the jumps,” Eustace recalls. “What I originally planned was like scuba diving through the stratosphere, but what I thought we could do and what we did was quite different.”

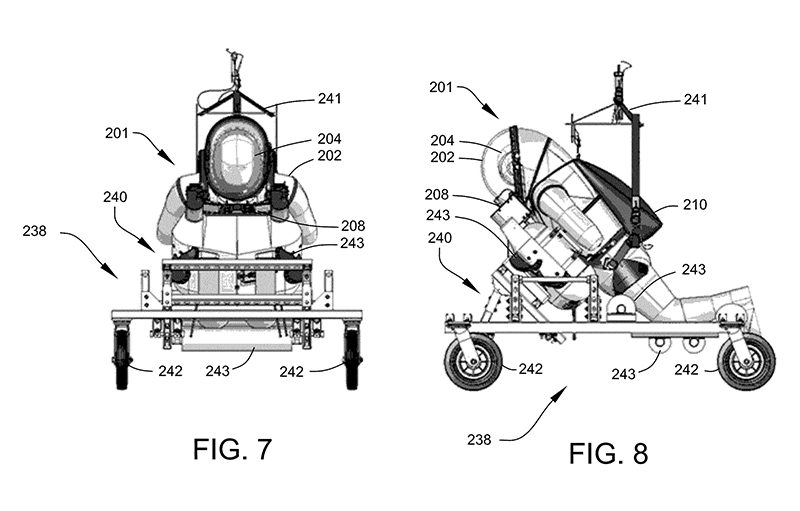

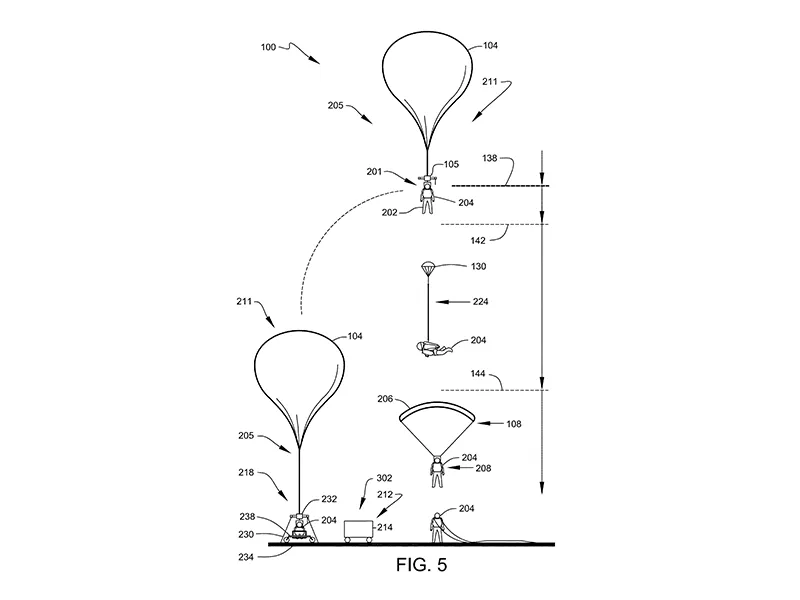

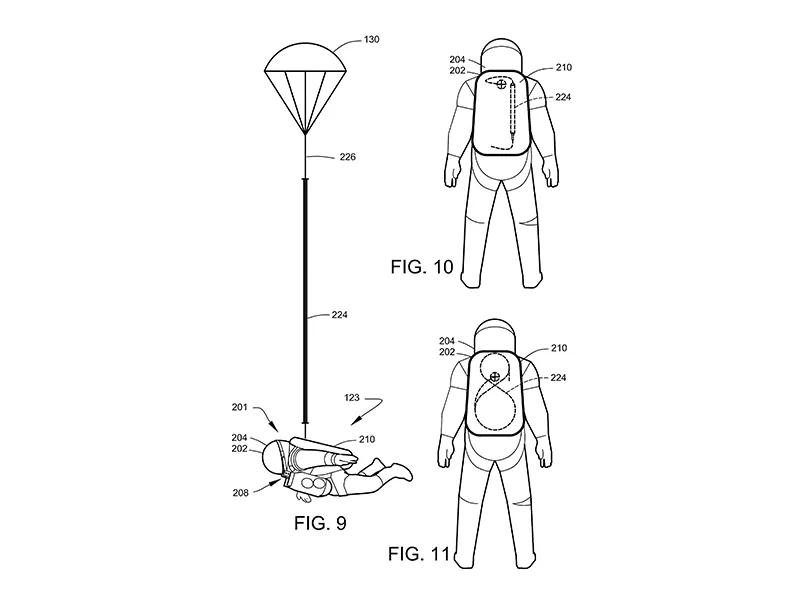

In a custom-made spacesuit fitted with a specially designed life support system, Eustace dangled beneath a balloon that ascended at speeds of up to 1,600 feet per minute. After about half an hour glorying in the view from 135,890 feet up, he detached from the football field-sized balloon. Eustace plummeted back to the surface in a free fall at speeds of up to 822 miles an hour, setting off a sonic boom heard by people on the ground. The entire trip from beneath the balloon to his landing took just over 14 minutes.

“Who would have thought that all by themselves, a team of maybe 20 people or less could basically build everything necessary to get somebody up to above 99.5 percent of Earth’s atmosphere, see the curvature of the Earth and the darkness of space and return to ground safely in a means that no one has ever tried before,” Eustace says. “For me, that’s the exciting part!”

The specially designed spacesuit Eustace wore, along with the balloon equipment module, is now on display at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. It is a combination of state-of-the-art materials and off-the-shelf technology, made by Paragon Space Development Corporation, United Parachute Technologies, and ILC Dover, which has made spacesuits for NASA since the Apollo Program.

Eustace, a veteran pilot and parachutist, founded StratEx, with the goal of developing a self-contained spacesuit and recovery system that would allow manned exploration of the stratosphere above 100,000 feet. He says his journey began several years ago, when a friend asked his advice about buying a large, sophisticated capsule similar to the one used by Felix Baumgartner in his record-breaking jump from 128,100 feet on October 14, 2012.

“I said if it was me, I wouldn’t do a big capsule. I would develop some sort of scuba system for the stratosphere. Imagine if you used a normal tandem skydiving rig. Instead of putting a passenger on the front which can weigh 200 pounds,” Eustace thought, “why not put an oxygen tank in there and then go in a spacesuit.”

Eustace got in touch with Taber MacCallum at Paragon, and asked if a system could be developed to allow a person to go into the atmosphere. After three years of work from a team of experts, he was able to make the jump.

ILC Dover had never before sold a spacesuit commercially, but the company sold one to Eustace. United Parachute Technologies was part of a team that designed the drogue parachute main and reserve canopies, as well as giving Eustace additional flight training. He says the team had to redesign many of the components as they worked to meld scuba technology with NASA spacesuit technology.

“I was interested in the technology of how you wed these two things together,” Eustace explains. “It was important because if you really can build this scuba diving thing for the stratosphere, it makes it possible to do all kinds of things in the stratosphere. . . . You can use that suit for anything you want to do—the highest parachute jump, or research, [remaining] up there for hours and hours. . . . Any of those things are possible using that suit. It was an enabler for lots of other potential uses.”

Eustace says the design of the whole system made it capable of much higher altitudes than the capsule system Red Bull was using when it funded Baumgartner’s jump, because it was much lighter in weight. He says the StratEx system could have been demonstrated at a lower altitude, but to prove a new technology will work; you have to go to the extremes to show proof of concept.

“To silence the many potential doubters, the best thing we could do was try the hardest possible thing at the highest possible altitude. Skydiving is the hardest possible thing compared to a balloon ride up and down. That’s a lot easier from a technical point of view than what we actually set out to do,” says Eustace.

There were several ground breaking technologies produced by the design team, including the Saber system which allowed Eustace to control the parachute without allowing it to tangle around him. That system released the drogue immediately, and was combined with a spin resistant system that eliminated the uncontrolled spinning Baumgartner battled during his jump.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/5a/5b5a090e-dcb4-4415-a578-5d3d9435f6ba/alaneustacecase0196web.jpg)

Cathleen Lewis, the Smithsonian’s space history curator, says the design team melded state-of-the-art technology with off-the-shelf equipment. “The people who do these sorts of things tend to be very conservative,” Lewis says. “They want to know that their materials and their equipment have a proven track record so it’s going to work. But even though they are conservative about new material, they are not so conservative about adopting existing materials and combining existing materials. It’s a wonderful example of their approach to innovation that takes existing things and makes them very new.”

Eustace wore a warming garment underneath the spacesuit adapted from the cooling garments used by SWAT teams and first responders to keep him comfortable during the ascent.

“I had two layers under the suit,” Eustace says. “The first was a very thin layer, mainly to wick perspiration, and the second layer was the Thermal Control Undergarment. . . . [It] has tubes that run through it, to circulate around either hot water or cold water around me. In flight, it was hot water.”

But at the top of the stratosphere where it gets very warm, design modifications were needed for the suit to keep dry air in his helmet so his faceplate did not fog. Lewis explains that 100 percent oxygen was pumped into the helmet of Eustace’s suit, and kept there via a neck damn, rather like a “tight rubber turtle neck.” He breathed into a gas mask that shunted the used CO2 and moisture to the lower portion of the suit, which kept the helmet from fogging. To conserve oxygen during the flight, Eustace kept his movements to a minimum, which also helped prevent him from overheating on the ground.

She adds that Eustace wore mountaineering boots, but his gloves were a combination of spacesuit technology with mountaineering gloves that had heating elements inside along with batteries.

The Smithsonian acquired the spacesuit and balloon equipment module from Eustace, after Lewis and senior aeronautics curator Tom Crouch reached out to ILC Dover and contacts in the ballooning field about getting the items. Eustace not only agreed to donate the spacesuit, he also funded the display as well as the museum’s educational programming over the next year.

Lewis credits the team with design excellence not only in the display, but also in its use of conservation measures to slow the suit’s decay—a regular air flow moves through the synthetic material in the spacesuit for climate control. The suit can be seen hanging from the bottom of the balloon equipment module, which was attached to a giant scientific balloon to carry Eustace into the stratosphere.

“It is suspended and floating in the air, and that’s just causing visitors to stop and look at it,” Lewis says. “It is very impressive because they are looking at the suit as if they are watching Eustace ascending into the stratosphere. That’s getting people . . . to ask questions. ‘What is this? What is it doing? How was it made? Who made it and why?’ We start to get them thinking like historians and engineers.”

Eustace also funded the entire mission; through he won’t say how much it cost.

“More than I thought by a lot,” he laughs. But he says the Smithsonian display allows visitors to imagine themselves dangling beneath a balloon looking down at the Earth, and it gives them a real perspective of what it was like during his journey to the stratosphere. The cost of the equipment, flight and display, he says, are more than worth it to him and the team that made it possible.

“If you look at anything at the Smithsonian and look at the stories, every one of those aircraft cost more than they thought,” Eustace says. “Everyone is equally proud that something they created found its way to the Smithsonian. For us, it’s like the pinnacle. That’s our Mount Everest if you’re a technologist and interested in aircraft.”

Alan Eustace's suit from his record-breaking freefall jump in October 2014 is on permanent view at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)