Some Stories About George Washington Are Just Too Good to Be True

But there’s a kernel of truth to many of them because Washington was a legend in his own time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/a7/8ca76e7e-01cf-4a2b-97ab-a230a6632a3c/grant-wood-painting.jpg)

Did young George Washington use a hatchet to chop down one of his father’s cherry trees, and then confess to the act because he could never tell a lie, even at the age of six? Did he throw a silver dollar across the Potomac River, perhaps half a mile wide? Folklorists refer to these stories as legends because many people believe them to be true, even though the stories cannot be authenticated.

Much about the life of America's first president seems prone to legend. After all, George Washington is the first of 45 U.S. presidents, the face on our most commonly circulated dollar bill, and the name of our nation’s capital city. In many ways, he has become larger than life, especially when depicted bare-chested and extremely buff in a 12-ton marble statue inside the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Even the date of Washington’s birth is subject to debate. He was born February 11, 1731, according to the Julian calendar that was in use at the time. When Great Britain and its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, they removed 11 days from the calendar to bring it into synch with the solar year. Accordingly, Washington’s birthday became February 22, 1732—and a national holiday in the United States from 1879 until 1971, when the Uniform Monday Holiday Act fixed it as the third Monday in February. Federal law still calls it Washington’s Birthday, although it is commonly known as Presidents’ Day.

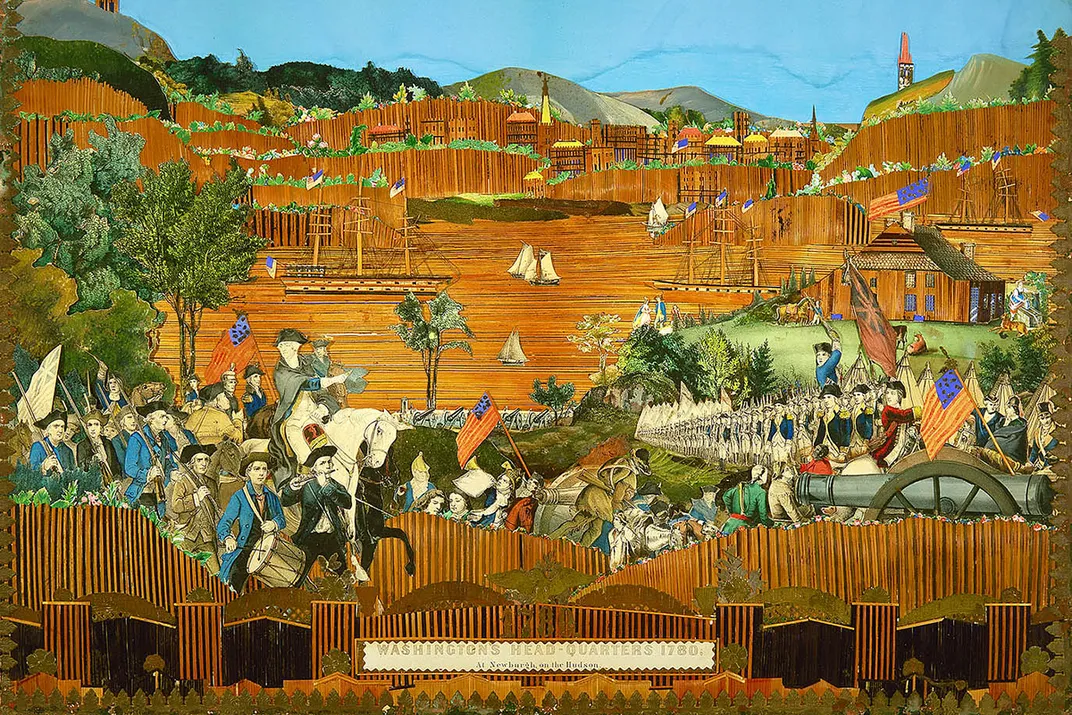

My own favorite story about Washington dates back to March 1783 in Newburgh, New York. Fighting in the Revolutionary War had ceased more than one year earlier, but the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the war, was not signed until September 1783. Drafting of the U.S. Constitution did not begin until May 1787, and Washington was not elected president until early 1789. So the state of affairs in the United States was very uncertain in March 1783. Officers and soldiers in the Continental Army were extremely discontent because they had not been paid in many months and wanted to return home. Animosity was growing toward General Washington, the Army’s commander-in-chief.

On Saturday, March 15, 1783, Washington surprised a group of officers by appearing at a meeting in which they were considering whether to mutiny, or even stage a military coup against the Congress of the United States. Washington had prepared a speech—now known as the Newburgh Address—which he read to the assembled officers. It did not go over well, but what happened next has become the stuff of legend.

According to James Thomas Flexner’s 1969 biography, Washington: The Indispensable Man, Washington thought that reading a letter he had received from a member of Congress might help his case. But when he tried to read the letter, something seemed to go wrong. The general seemed confused; he stared at the paper helplessly. The officers leaned forward, their hearts contracting with anxiety. Washington pulled from his pocket something only his intimates had seen him wear: a pair of eyeglasses. “Gentlemen,” he said, “you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.” This homely act and simple statement did what all Washington”s arguments had failed to do. The hardened soldiers wept. Washington had saved the United States from tyranny and civil discord.

It’s a beautiful story, one that memorably captures Washington’s ability to connect on a very human level with the troops he commanded, as well as his willingness to reveal his personal vulnerability—an admirable trait that today is perhaps too infrequently displayed by our military and political leaders. But it’s also a story that raises suspicions among folklorists, who know the proverb, “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” and who also know that multiple variants often indicate a story’s folkloric quality.

For instance, the well-known urban legend about an excessively long government memo regulating cabbage sales has slight variants affecting the number of words, the subject of the memo, or the issuing agency. Similarly, there are slight variants to what Washington is supposed to have told the assembled officers. Sometimes he is growing gray, sometimes growing old, sometimes growing blind, and sometimes almost blind. The kernel of the story remains consistent, which is also key to the process of legend making. After all, on the third Monday in February, we can never tell a lie. Or something like that.

A version of this article previously appeared on the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/James_Deutsch.jpg)