The Smithsonian’s Innovation Festival Demystifies the Invention Process

Inventors of a number of new technologies shared their stories at a two-day event at the National Museum of American History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/ab/40ab5ada-640c-4cf1-bf79-f758a0dda1e7/linedupforfestival.jpg)

When Matt Carroll answered the phone earlier this year and learned a patent had come through for his invention, WiperFill, he didn’t believe the caller. “I thought it was a friend messing around with me,” he said. “I thought it was just someone playing a joke.”

Carroll’s product, which collects rainwater from windshields to replenish cars’ wiper fluid reservoirs without relying on power, sensors or pumps, was one of more than a dozen showcased at the Smithsonian’s Innovation Festival, organized with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office at the National Museum of American History this past weekend.

The patent that Carroll received in April was the 9 millionth that the USPTO issued. “They called me and said, ‘Hey. You’re patent number 9 million.’ I said, ‘9 million and what?’ They said, ‘No, 9 million,’” Carroll said, admitting he didn’t initially appreciate the significance of the elite club of milestone million patent holders which he was now a member.

“Joining the ranks of an auto tire and ethanol and all these different really awesome patents, it’s really special,” he said.

The south Florida-based construction company owner conceived of the idea driving back and forth on the hour-and-a-half commute between his company’s two facilities. “I’m constantly running out of windshield wiper fluid. It drove me nuts,” Carroll said. “I drove through a rain shower one day and got the idea for WiperFill.”

Showing his invention at the festival, where he estimated about 200 people had stopped by his booth in the first couple of hours, was “validation,” Carroll said. “I talk to industry people, and they are like, ‘Wow. It can do this and this and this.’ But talk to the consumers—people who are actually going to be using it—and you get a whole different view of your product.”

That interaction is just what the festival organizers hoped to broker, according to Jeffrey Brodie, deputy director of the museum’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation.

“Everyone’s got innovation on the mind. Everyone is very interested in what innovation has the power to do in terms of changing their lives and driving the economy,” Brodie said. “What the festival does is give the public the opportunity to peel back the layers of the onion to get an idea of who inventors are, how they work and where the ideas come from. These ideas and these inventions that change our lives don’t just come out of nowhere.”

The goal was also to help visitors realize that they too can invent. “Introducing the public to the people who are working in the Patent and Trademark Office sort of demystifies the process; it changes it from being an institution and a building to a set of people who are there to assist and help promote the circulation of new ideas,” he said.

Elizabeth Dougherty, director of inventor education, outreach and recognition at the USPTO’s Office of Innovation Development, gave a presentation, “Everything you always wanted to know about Patents (but were afraid to ask),” on the nuts and bolts of intellectual property.

“Trademarks are an identifier of the source of goods or services. What I think a lot of people don’t recognize is that trademarks aren’t always just a word or a symbol,” she said in an interview. “They can be a word or a symbol. They can be a combination of a word and a symbol. They can sometimes be a color. They can be a shape. They can be a sound.”

The range of patented objects became immediately apparent, wandering between tables with presenters as varied as Kansas State University, which presented hydrogels, useful to researchers for their ability to change from jelly-like to liquid form, and Ford Global Technologies, which displayed its Pro Trailer Backup Assist, to help drivers of its 2016 F-150 pickup truck reverse their trucks.

“It’s really nerve wracking trying to back up a trailer efficiently and well,” said Roger Trombley, an engineer at Ford. “What this system does is it uses a sensor to detect the trailer angle, and then with the algorithms we have in there, you actually steer a knob instead of the steering wheel.”

At an adjacent booth, Scott Parazynski, a Houston-based former astronaut who teaches at Arizona State University, explained that he has spent two seasons on Mt. Everest, including at the top. His invention, a Freeze Resistant Hydration System, heats a water reservoir that the climber carries inside his or her suit, and not only keeps the water warm with a heating loop (and prevents the straw from freezing), but also allows the climber to benefit from the heat.

“The genesis of my technology actually hails from my years in the space program; I flew in five space shuttle missions. We had lots of different technologies to control temperature,” he said. “We experienced these incredible temperature shifts going around the Earth. When we are in direct sunlight, we can have temperatures upward of 300 degrees Fahrenheit ambient temperature, and behind the Earth in orbital night we can be minus 150 or below.”

At a U.S. Department of Agriculture table, Rob Griesbach, a deputy assistant administrator at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, gestured toward a table of peppers. “Wouldn’t it be nice if we could create a brand new pepper that had an orange fruit, that was shaped like a pumpkin, that would have black leaves, and they’d be upright?” he said. “Through conventional breeding, 15 years later, we actually finally came up with that particular plant.”

It was “almost like a Mr. Potato Head,” he added, noting a Mr. Potato Head on the table. “Why do vegetables have to be ugly looking? Why can’t we make a vegetable that looks nice?” he said. “People know USDA, and they think Grade A eggs and things like that. They don’t realize that USDA does a lot of things.”

At a table nearby, shared by Mars, Incorporated, the candy company, and one of its brands, Wrigley gum, Donald Seielstad, a process engineer who has worked at Wrigley for 17 years, talked about a patent Wrigley holds for a delayed-release of flavor in gum. “We call it like a flavor sponge,” he said. “We can soak flavor into an ingredient that we make before we add that ingredient to the gum, and it will help extend and delay the release of the flavor from the gum while you’re chewing it.”

Mars’ John Munafo discussed his employer’s patent for a white chocolate flavor. “White chocolate actually has low levels of a natural flavor in there, but if you increase the level of it, people prefer it,” he said. “White chocolate is one of those chocolates that’s interesting; people either love it or hate it. What we found is that if you add low levels of this flavor that’s naturally occurring, but enhance it, then people prefer it.” (The flavor’s technical name? Isovaleric acid.)

While Munafo spoke, a young girl came over and interrupted the interview, holding up a bag of M&Ms. “I love this candy. Do you make this candy?” she asked. “We do,” he told her.

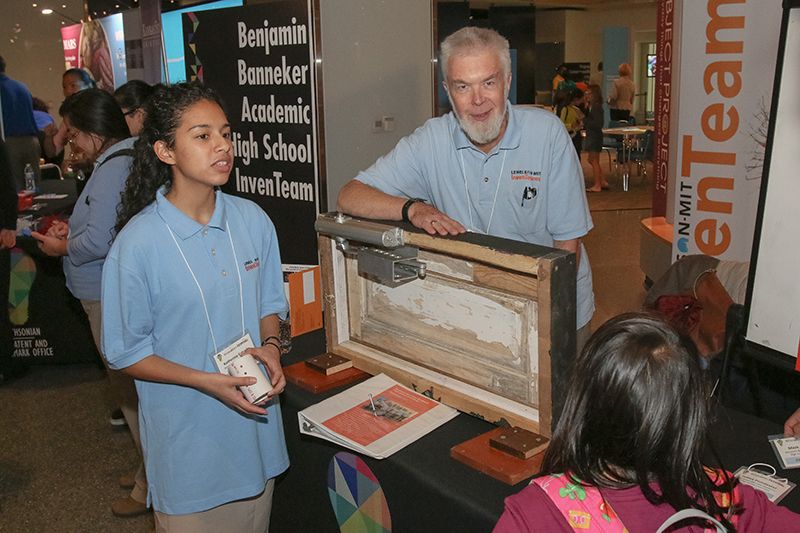

She may have been one of the youngest attendees of the festival, but several other young people—these high school age—were demonstrating an invention of their own, which they produced at Benjamin Banneker Academic High School in Washington. Their patent-pending invention, DeadStop (which earned the inventors a trip to Lemelson-MIT’s EurekaFest), fits over the hinges of a classroom door and secures the door from the inside in the case of an emergency on campus.

“The DeadStop goes over the door and slides through the hinges, so the pressure isn’t just exerted on the nails,” said Katherine Estrada, a senior. “We had 15 students on the invent team at the time that the DeadStop was created, so it went through a lot of experimentation. Just imagine 15 kids trying to open the door. It was impossible.”

“This is exciting. It’s real ratification of all the work that our students have done,” said John Mahoney, a math teacher at the school. “I didn’t know what engineering was when I was in school—it’s just applied math.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)