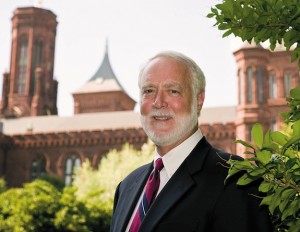

Smithsonian Secretary Clough Connects the Dots on Climate Change

Clough says that the institution must pair its cutting-edge research with more effective communication of climate science to the public

![]()

The impacts of Hurricane Sandy, among other events, convinced Clough that the Smithsonian needs to pair its cutting-edge research with more effective communication of climate science to the public. Image via NASA

“What we have here is a failure to communicate,” said G. Wayne Clough, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, reflecting on the Institution’s role in educating the public about climate change. “We are the world’s largest museum and research center. . .but if you wanted to find out something about climate change and went to the Smithsonian website, you’d get there and have trouble finding out about it.”

In “Climate Change: Connecting the Dots,” a wide-ranging speech the Smithsonian secretary made today about the state of climate science and education at the Smithsonian, Clough conceded that, while the Institution has led the way in many fields of scientific research relating to the issue, it’s been less effective at conveying this expert knowledge to the public. “We have a serious responsibility to contribute to the public understanding of climate change,” he said.

Clough recently decided that communication the issue is a priority, he said, while contemplating the unprecedented damage of Hurricane Sandy and its link to climate change. Previously, while speaking to friends and outside groups about the impacts of climate change in other areas, such as the Yupik people of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait, or the citizens of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, he’d frequently encountered an attitude of apathy.

“I would tell all of my friends, ‘this is a big deal,’ and inevitably, what they told me was, ‘well, those people in New Orleans build houses at places that are below sea level,’” he said. “‘That’s their problem, that’s not our problem.’”

The tragic consequences of Hurricane Sandy, though, have changed the climate of discussion around the issue. “Sandy and some other recent events have made this easier. You cannot run away from the issues we’re facing here,” Clough said. “Suddenly, it’s now become everyone’s problem.”

In response to this problem, he announced a pair of initiatives to expand the Smithsonian’s role in climate science. The Tennenbaum Marine Observatories will serve as the first worldwide network of coastal ocean field sites, designed to closely monitor the effects wrought by climate change in ocean ecosystems around the globe. TEMPO (Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution), conducted by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, will be the first space-based project to monitor pollution in the North American upper atmosphere in real time.

These will join dozens of climate-related research projects that have been ongoing for decades—research on wetlands, oceans, invasive species, carbon sequestration by ecosystems, wisdom on climate change from traditional cultures, historical changes in climate and other fields.

For an Institution that has become embroiled in controversies over public education on climate change over the years, making the issue an overall priority is significant. Clough feels that an inclusive approach is key. ”Let’s start with the idea that everybody’s educable, that everybody wants to learn something, and they’re going to go someplace to try to learn it,” he said. “No matter who you are, I think the place that you would want to come is the Smithsonian. So part of our communications task is to bring as many people to the table as possible to have this discussion.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)