Iranian Exile Shirin Neshat’s New Exhibition Expresses the Power of Art to Shape Political Discourse

An exhibition of the artist’s work at the Hirshhorn is an allegorical narrative framed against historical and political realities

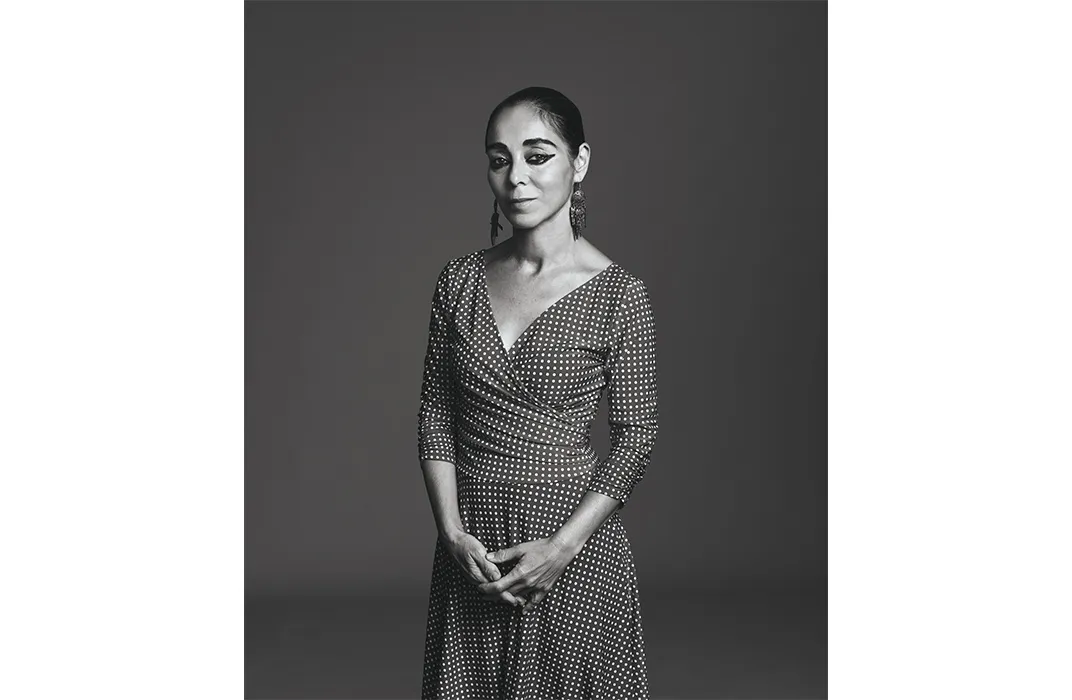

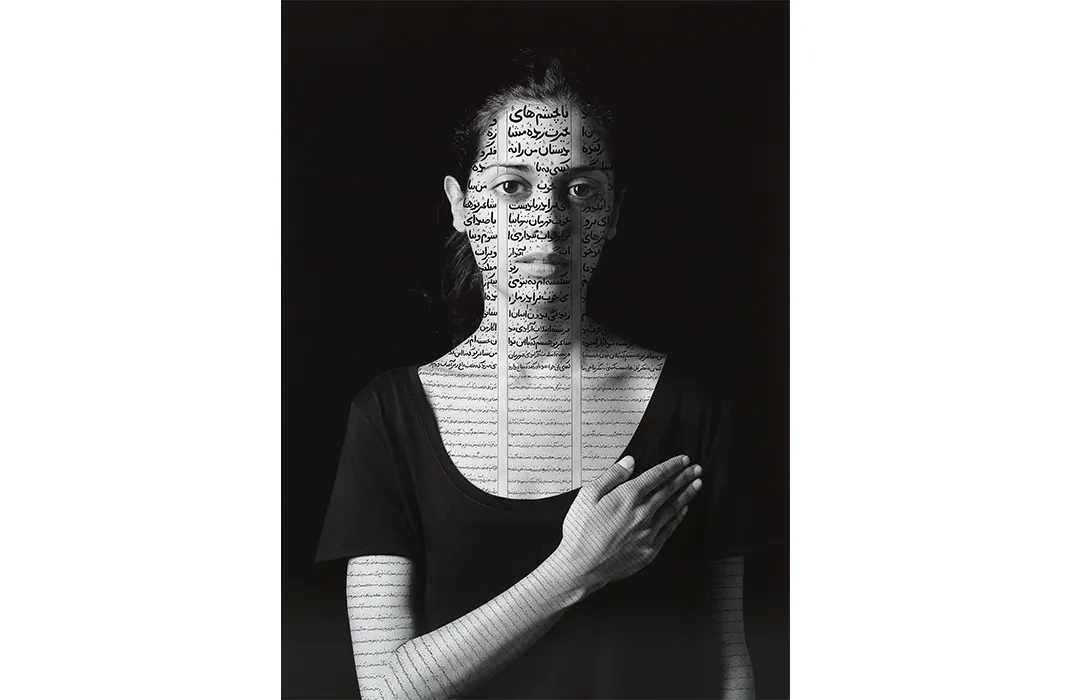

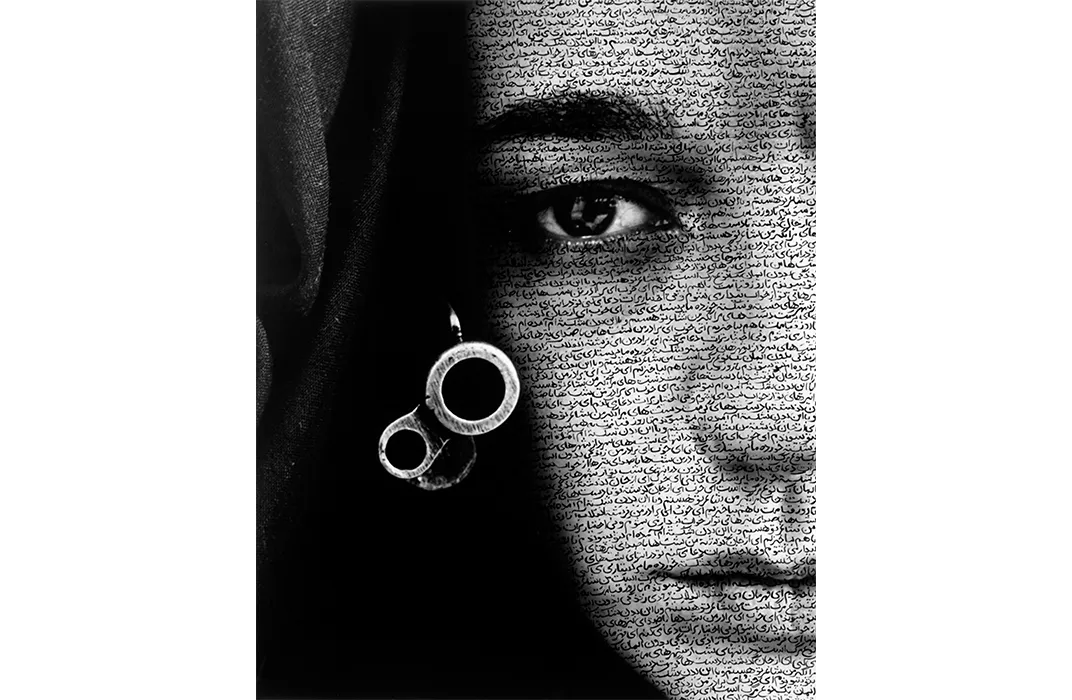

Shirin Neshat, a slight woman with heavy eyeliner, stood against a wall displaying 45 of her photographic portraits—the faces were covered with inscriptions of Farsi poetry. The Iranian-born artist was taking questions from journalists at a press preview of her solo exhibition in Washington, D.C. at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, just blocks away from Capitol Hill, where lawmakers have recently been debating the merits of an historic agreement between the U.S. and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

She told one woman, “I am not a feminist,” which drew some disbelieving laughter from the crowd. Two questions later, a man began, “I don’t want to get into the whole question of why you don’t consider yourself a feminist, because I thought this was a deeply feminist show.”

He had a point.

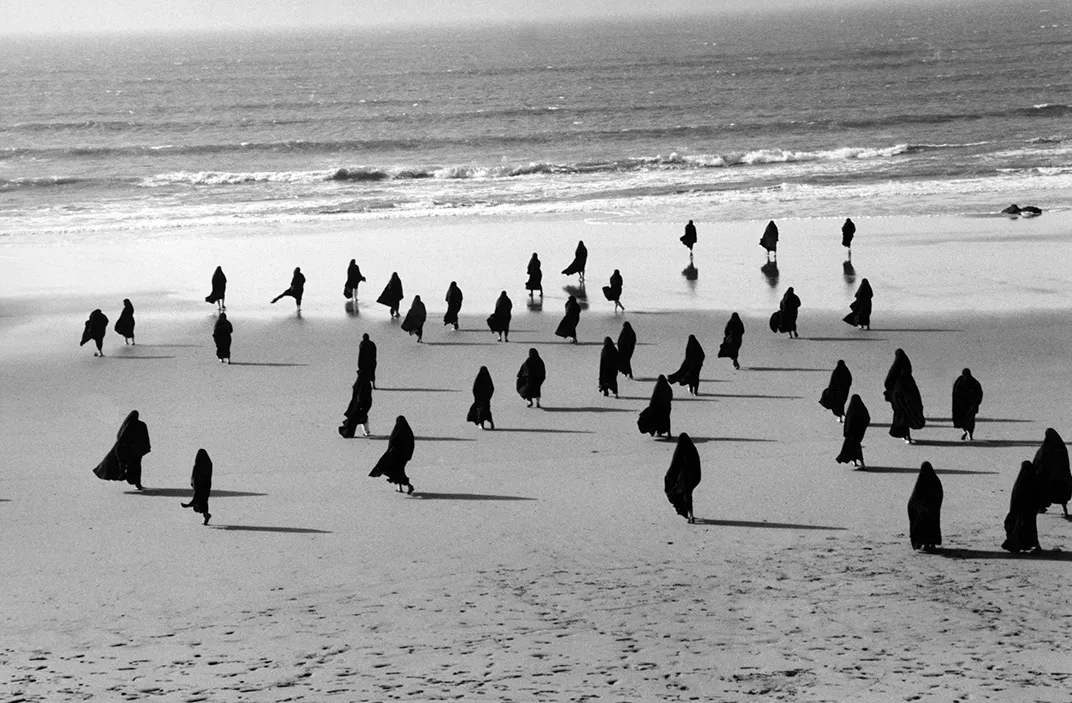

So much of Neshat’s art engages questions of Islam and gender issues. In the film Fervor, on view in the museum’s exhibition “Shirin Neshat: Facing History,” a woman in a headscarf seems to barely tolerate an imam railing about sexual license before she rises from the women’s section and exits the hall in protest.

Another film, Turbulent, features two separate screens. On one, a male singer performs before an all-male audience the lyrics of the 13th-century Iranian mystical poet Rumi, while on the other a female musician sings to an empty hall. The message of gender inequality in both Fervor and Turbulent is undeniable.

Born in Iran in 1957, Neshat came to the United States as a teenager to study. The Iranian Revolution marooned her stateside in 1979. After earning graduate degrees in painting and printmaking at University of California, Berkeley, she moved to New York in 1983. In the early 1990s, she returned to Iran on multiple occasions, but fearing for her safety, she has not returned since 1996. Thus one can’t help but view her works through the lens of an exiled artist—collages of elements call to mind Iranian history, contemporary Iranian politics and orthodox religion.

Although profoundly critical of many of the changes Iran has undergone, Neshat refers to her work as nostalgic. She is emphatic that her works are entirely contrived, and the product of much poetic license. “My work is a work of fiction,” she says.

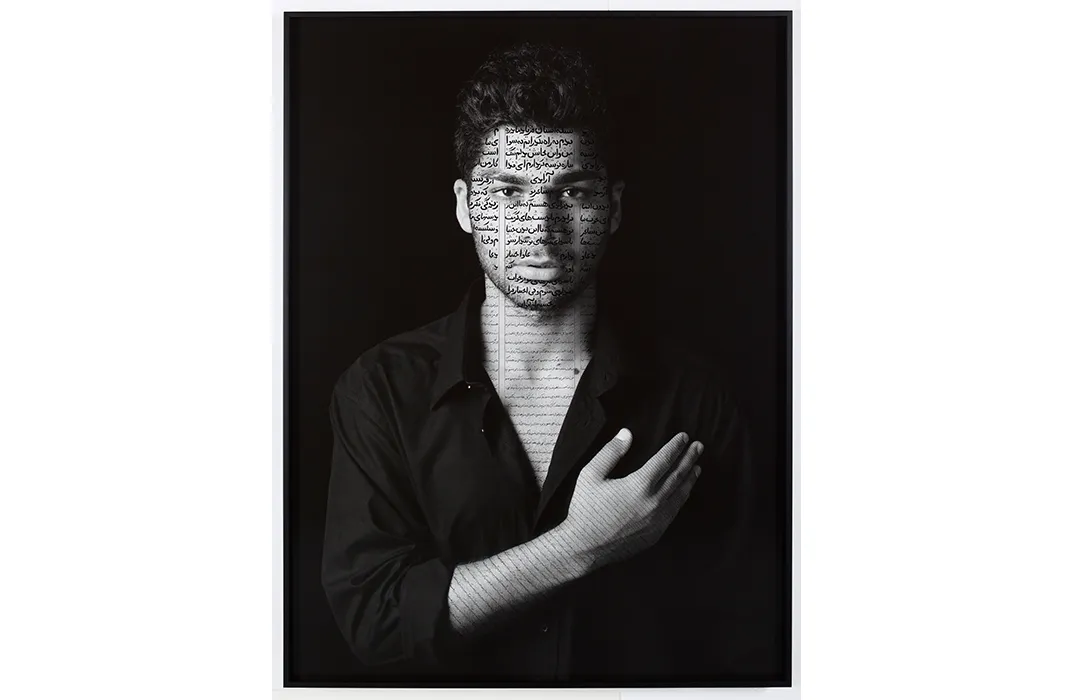

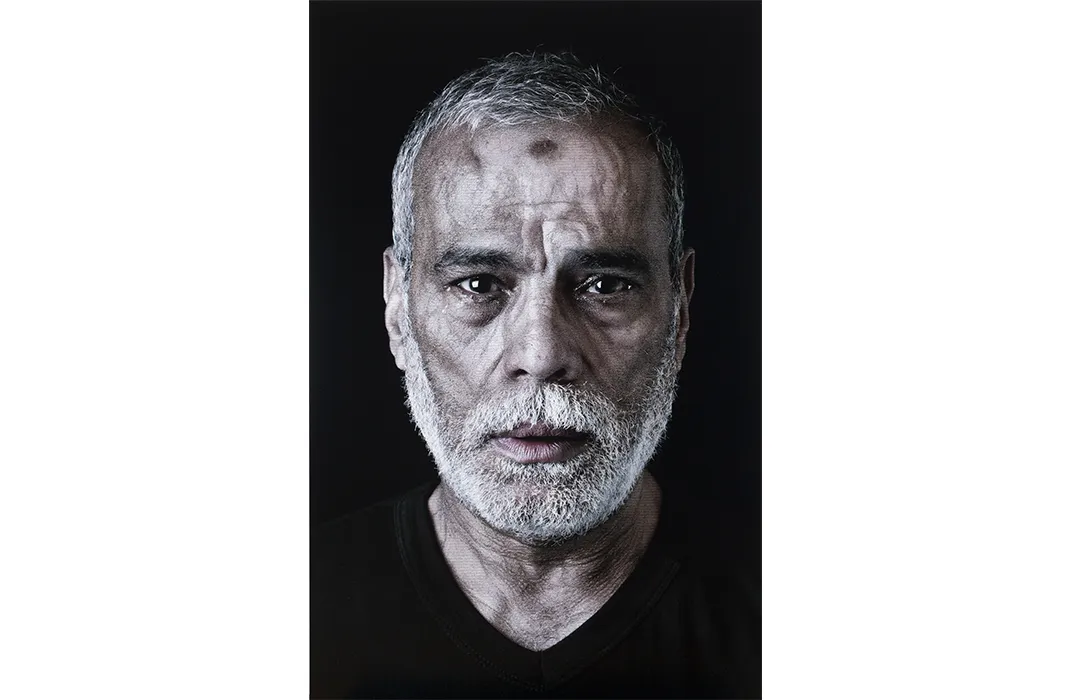

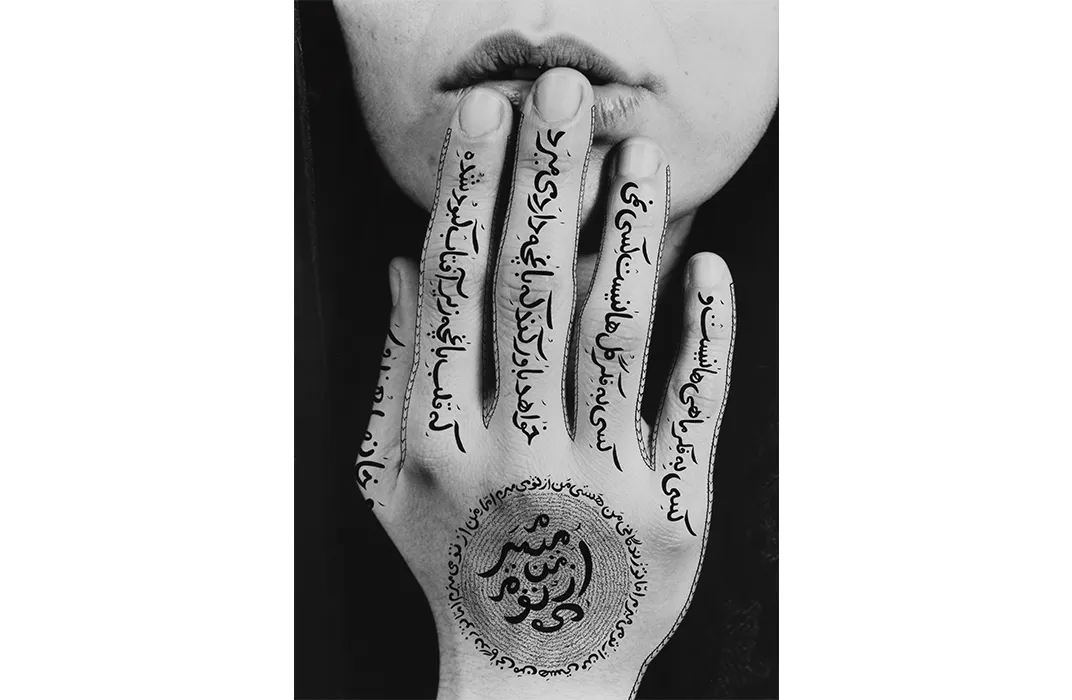

Besides her film works, Neshat creates bold photographs that display properties typically endemic to monumental sculptures. The works make viewers acutely aware of the spatial relationship between themselves and the art. Visitors typically approach the photographs as they would Chuck Close paintings—admiring the realism from afar, and then creeping ever closer—beneath the watchful eyes of the guards—to study the layers and abstraction.

Over the past two decades, Neshat’s work, such as her seminal Women of Allah series photographic series (1993-97), has become so identified with questions surrounding gender politics within the Islamic Republic of Iran that critics have pounced on later works and dismissed them as the products of a one-trick pony.

“One wants this work to do something, be more ambitious, aim for something deeper,” the Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott wrote of a 2013 series entitled Our House is On Fire of documentary portraits of men and women from Egypt. “But in the end it feels like Neshat has simply applied the Neshat brand to another country, processing its suffering in her usual style without adding much to the wall of sad, painfully weary faces.”

Others see things differently. “Whenever a critic only has negative things to say, I wonder,” says Shiva Balaghi, a professor of Iranian studies currently at Brown University, who notes that beginning in the 1990s, Neshat was one of a very few visual artists tackling these questions. Her work has been exhibited at least twice in Iran—both during the 1997-2005 Mohammad Khatami’s presidency, says Balaghi. “Iran-based artists tell me that they follow her work very closely [online],” she says. “One artist told me when travelers arrive from the U.S., they are regaled with questions about Shirin. Whether they like her art or not, they follow it.”

“For its time, that series was original and important,” she adds, referring to the Women of Allah. “Shirin is the first-ever Middle Eastern artist and first woman artist since 2009 to receive recognition in a monographic show at the Hirshhorn.”

Sherri Geldin, who directs Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts where Neshat created Fervor in residence in 2000, says the artist is under enormous pressure here in the West as a cultural interpreter. “Given Shirin’s now prominent stature among critics in the West as an ‘expat expert’ on Islamic culture, might they not be heaping an excessive burden on this single, and singular, artist in expecting that her work consistently fuse the ever more explosively-disputed facets of that system of beliefs?” she says.

At the Hirshhorn, Neshat’s solo show is not only the first major survey of her work at an East Coast museum, but it also is the first exhibition under the tenure of the museum’s new director Melissa Chiu, who assumed the position last September after overseeing New York City’s Asia Society Museum. Typically, the museum’s exhibition design has been studies in a subtle grayscale, but for the Neshat show, some of the walls are glowing with crimson.

“There hasn’t been a ton of use of colors in our shows; it was kind of new territory for us,” says Melissa Ho, who co-curated the show with Chiu. “We knew we wanted rich color, but we still wanted it to be elegant, because her work is very elegant.”

And rather than organizing the works as a progression of Neshat’s development as an artist—from painter to photographer to video artist to cinema, Ho and Chiu chose an historical chronology. Neshat’s artwork, period photojournalism, and objects, are displayed against the backstory of the 1953 overthrow of then-Iranian prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the “Green Movement” protests of the 2009 Iranian election and the ensuing Arab Spring.

The complexity and controversy surrounding the artist’s work surface in her Women of Allah series, which depicts veiled women with their faces inscribed with lines of verse by two Iranian poets. One is apologetic toward the revolution and orthodox Islam and the other takes an opposite perspective—criticizing the restrictive attire for women prescribed under the revolution.

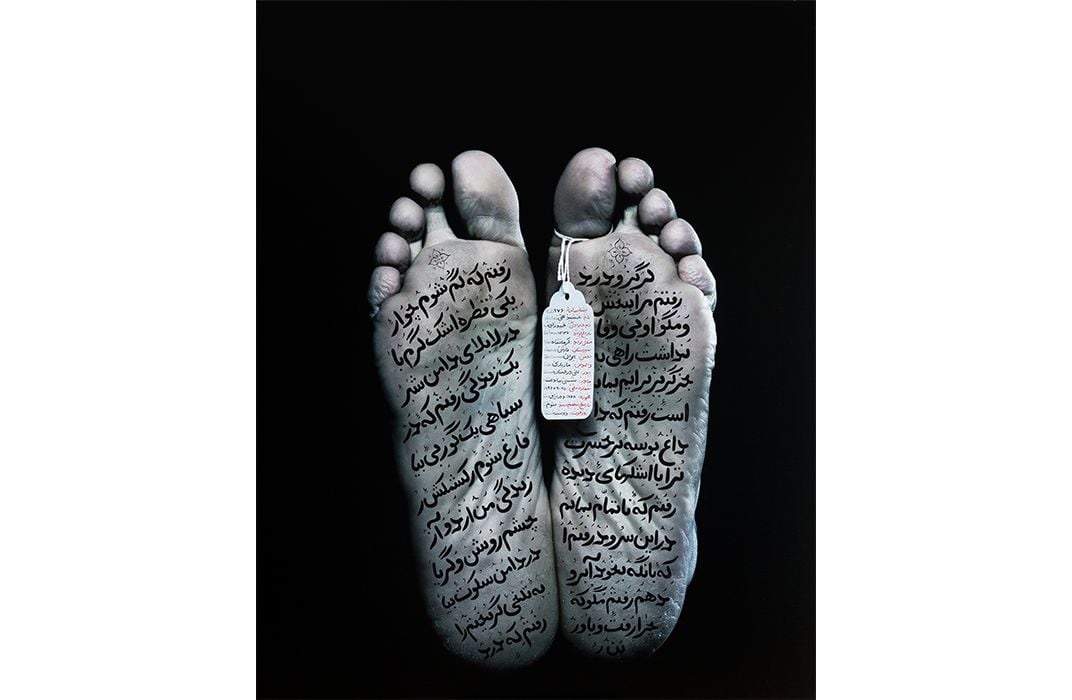

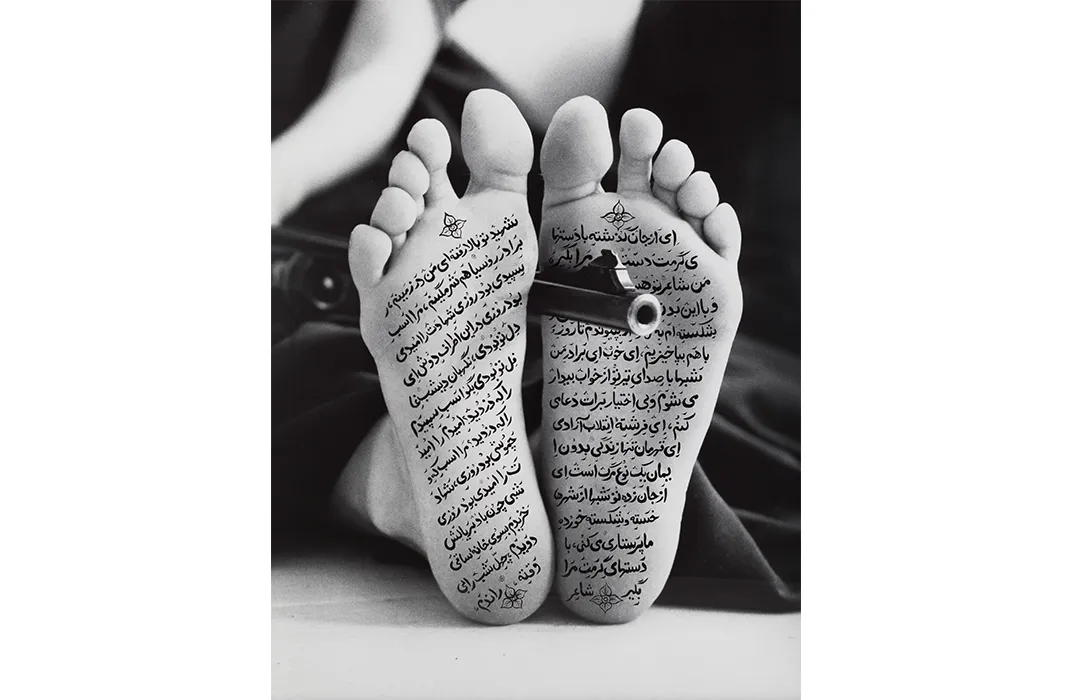

In Allegiance with Wakefulness, part of the series, the barrel of a rifle emerges from between a pair of feet, each inscribed with Farsi poetry. The feet anchor the gun and suggest either vulnerability or aggression. In Bonding and in Grace Under Duty, the writing looks simultaneously like snakeskin and Henna designs, and a wall text featuring an excerpt of a poem by Tehereh Saffarzadeh —“O, you martyr … I am your poet … we shall rise again”—underscores the kind of crosshairs that is not only trained on Neshat’s models, but also on her as an artist. Neshat has said that she simultaneously faces criticism from some for sympathizing with martyrs and from others for being anti-Islam.

How the works fare in Washington remains to be seen, but the location is significant to Neshat, whose prior experience with D.C. was restricted to visiting “the consulate.” Now as U.S.-Iranian relations are at the forefront of political discourse, Neshat appreciates an exhibition that places her works at the center of the “capital of politics.”

Ho notes that the exhibition is framed by “an interesting time,” but she points out that Neshat has lived in the United States much longer than she did in Iran. “I don’t think any artist likes saying, ‘I’m representing my nation.”

“It’s not necessarily a case of cultural diplomacy. It’s more an artist concerned about social justice and freedom of speech and democracy,” says Ho. “I think that’s what is resonant with the location on the National Mall, which of course is a site itself deeply imbued with symbolism of democracy, and participation, and citizenship, and a voice on a national scale.”

“Shirin Neshat: Facing History” is on view at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., through September 20, 2015.

Shirin Neshat: Facing History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)