See 19th-Century London Through the Eyes of James McNeill Whistler, One of America’s Greatest Painters

The largest U.S. display in 20 years of Whistler artworks highlights the artist’s career in England

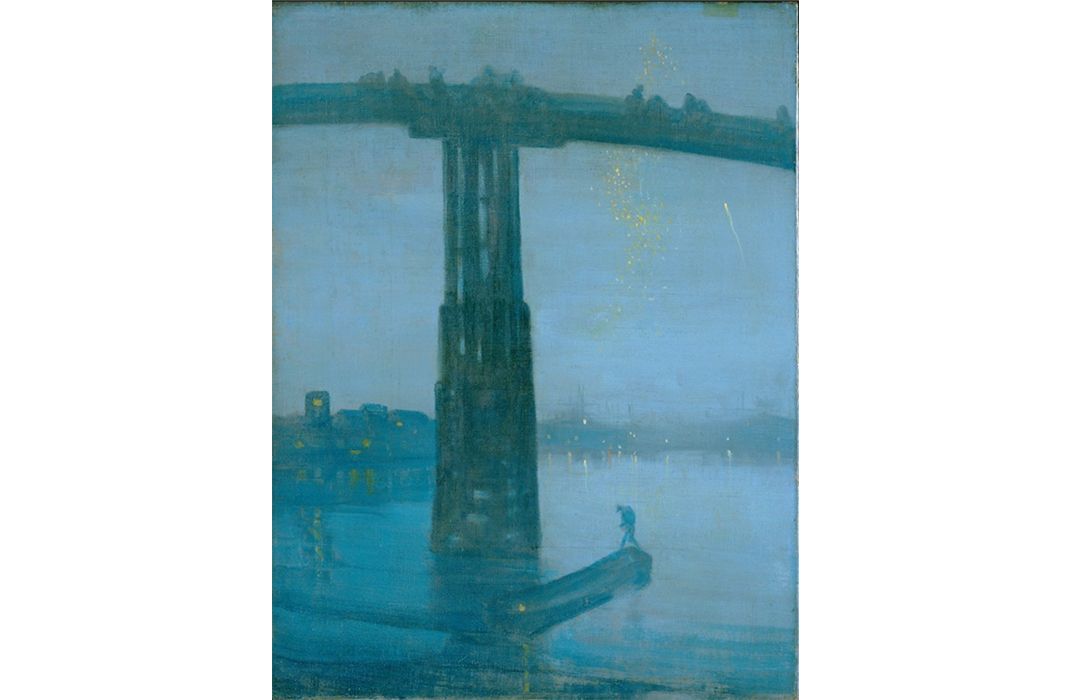

In the 1872-1873 artwork Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge, a boat slips across a glass-still Thames River, manned by a ghostly passenger. Behind the watercraft looms a tall, wooden overpass. Its silhouette is dark against the deep blue sky; a spray of golden rockets fizz on the horizon. Shadowy figures huddle on top of the bridge, perhaps to watch the fiery spectacle. The subject matter is decidedly Western. Its composition, however, evokes comparisons to Japanese woodblock prints.

Created by the iconic James McNeill Whistler, the painting is famous for its role in one of the 19th century’s most infamous libel suits. (Whistler sued art critic James Ruskin after the latter wrote a disparaging review, denouncing the artist as having flung "a pot of paint in the public's face." Nocturne: Blue and Gold served as the trial's evidence.) But the scene also encapsulates Whistler’s artistic evolution in London, a process fueled by his fascination with the bustling Thames and later refined by close study of Far Eastern art.

The Nocturne is one of more than 90 works featured in “An American in London: Whistler and the Thames,” currently on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. It is the first show devoted to the American-born Whistler’s early years in England—the sights, structures and aesthetics that shaped his singular portrayal of Europe’s busiest port. It’s also the Smithsonian’s only exhibition of art by Whistler to include paintings on loan from other museums, and the largest display in the United States in nearly 20 years to feature the master painter’s work.

“An American in London” began a three-city tour at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, followed by the Addison Gallery of American Art in Massachusetts. Now that the traveling show has arrived for its final curtain call at the Sackler, its objects—borrowed from museums in Europe and around the U.S.—have been combined with nearly 50 Whistler paintings, etchings and other such masterpieces from the adjacent Freer Gallery. Viewers have the rare opportunity to see these artworks displayed together for the very first time, allowing them to trace the painter’s gradual journey from realism to Japanese aestheticism.

Whistler, who was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, arrived in England during the late 1850s; a period in which his newly adopted country still reeled from the Industrial Revolution. There, Whistler gleaned inspiration from his shifting surroundings.

The River Thames, in particular, coursed with the vestiges of modernization and pollution. Barges filled with cargo and workmen traversed its murky waters, and factories lining its shores belched smog into the air. And taking in the landscape from his first-floor studio window was Whistler, whose home overlooked the waterway.

“The Thames was a gritty, dirty river at this time,” says Patricia de Montfort, an art history lecturer at the University of Glasgow and one of the exhibition’s co-curators. “It was a time of change; it was a time when the river was a major shipping way. This is what Whistler was observing obsessively every day for nearly 40 years of his career.”

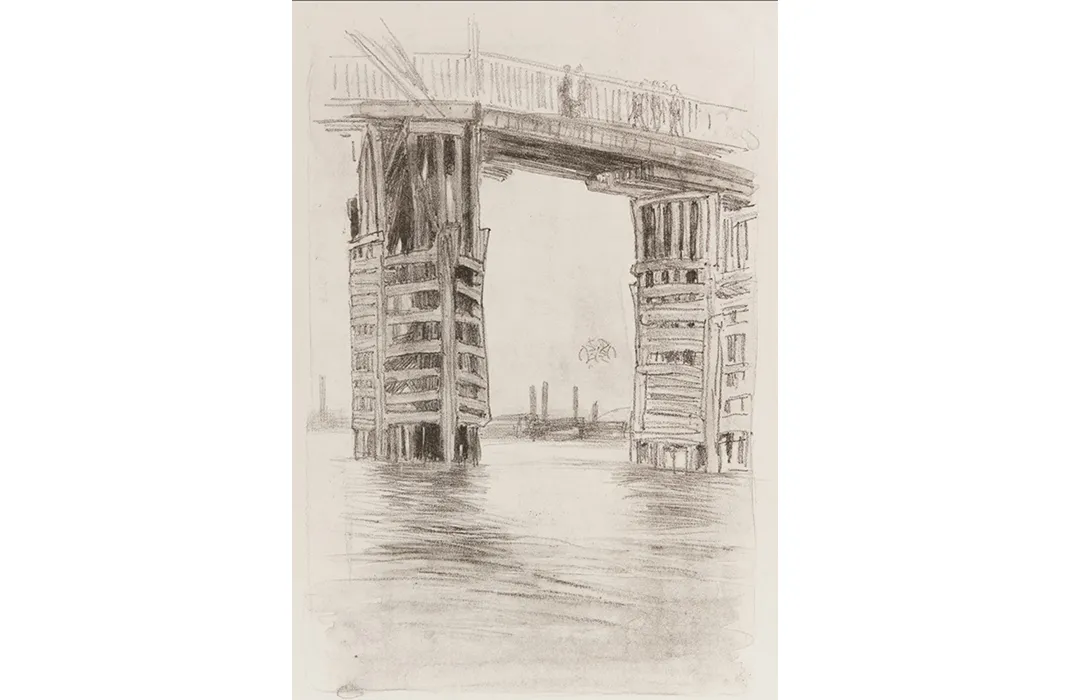

One of the first paintings shown in the exhibit—Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1859–1863)—was also one of Whistler’s first London works. The picture shows an old timber bridge, which once spanned the water between Chelsea and Battersea and was later replaced by a newer crossway. London’s art establishment praised its “English grey and damp” and its “palpable and delightful truth of tone.”

“The realism of his Thames depiction was quite plain,” says Lee Glazer, the Sackler’s associate curator of American Art. “He earned an early reputation as a young artist for his accurate—but still evocative—depiction of these scenes.”

As the river transformed, so did Whistler’s paintings and etchings. He moved upstream—and up market—from the East End of London to Chelsea. There, he still painted the Thames, but his scenes became more poeticized.

The exhibit’s paintings, etchings, drawings and other works are organized to trace Whistler’s footsteps from the Thames’ northern bank to Chelsea. (Two maps—including an interactive, zoomable one—also detail Whistler’s numerous vantage points.) But the show, after taking visitors on a tour of the Victoria-era Thames, takes an international turn, leaping across the globe to mid-19th century Japan.

As Whistler’s London adapted to modernity, Japan was also in transition. In 1854, a mere five years prior to Whistler's arrival in England, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy pressured Japan into lifting its embargo on foreign shipping. Japanese prints and art flooded into Europe, and were prominently exhibited in Paris and London.

By 1867 Whistler had moved to Chelsea, and to a fresh perspective from which to paint Battersea. There, he befriended a neighbor, the artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The two shared an admiration for Japanese woodblock prints by artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige; Whistler especially loved their composition and colors.

Whistler was already incorporating Asian art and clothing into his paintings, including the 1864 Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen and Symphony in White No. 2: The Little White Girl. He also collected woodblock prints, and often borrowed props from Rossetti. In the exhibition, a series of such woodblock prints and fans by Hokusai and Hiroshige hang adjacent to Whistler’s Japan-inspired oils. The imported art is decorated with curved bridges and flowing rivers—Eastern doppelgängers of Whistler's beloved Thames and Battersea.

By 1871, Whistler’s influences—the Thames and Japanese art—merged together in his Nocturnes. The hazy evening scenes feature delicate lines and translucent washes of paint; named for a pensive musical term, they are considered by many to be his masterpieces.

The show concludes with a host of other Nocturnes, including the one from the Ruskin trial. The ethereal, almost abstract depiction of Whistler’s favorite bridge is bathed in a deep blue twilight. The structure is covered in textured mist, and its abbreviated lines and asymmetrical composition are a far cry from the realism of Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge. Instead, they're unmistakenly reminiscent of a Hiroshige work.

Like the lyrical melody it’s named for, the painting’s notes come together to form a singular vision—a new view of London that was prompted by the Thames, molded by Japanese art, but was nevertheless entirely Whistler’s own.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b8/66/b86684ee-2f58-49bd-8ace-72f7a248808d/whistler7jpg__1072x0_q85_upscale.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/c5/22c56fa2-55a8-4f6c-9cd4-79384d815517/whistler13.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)