The Romance and Promise of 20th-Century Radio Is Captured in This Mural

At the Cooper Hewitt, a rare opportunity to view “The World of Radio” with its masterful vignettes celebrating the Modern age

The powerful influence of the radio age still resonates today in this era of streaming music, podcasts and smart watches. A new exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum takes visitors back to the romantic dawn of radio, by spotlighting the medium’s artistic design, and one large textile mural in particular.

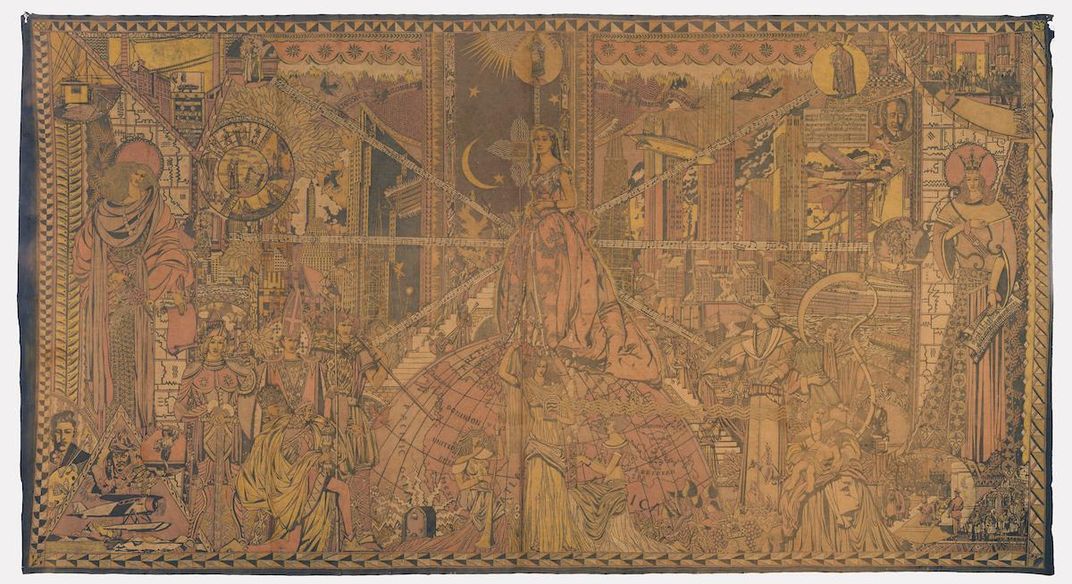

A voluminous, 16-foot-wide batik mural, entitled The World of Radio and crafted in 1934 by Canadian artist Arthur Gordon Smith is striking for the density of its imagery, symbols and patterns that together tell the history of radio technology, illustrate its cultural significance and honor one of the medium’s first superstars.

That would be Jessica Dragonette, the soprano opera singer who gained fame across the country and once brought 150,000 fans to a performance at Chicago’s Grant Park, thanks to regular appearances on the nascent medium.

“She was young, radio was young, and she decided to grow with the new medium—radio was the entertainment and communication medium of the 1920s,” says Kim Randall, curator of the show. The youthful and striking Dragonette stands atop a globe at the center of the mural, wearing a long dress and gazing into the distance in a pose fit for a “Queen of Radio,” as she would become known. Lines radiate from her in all directions (they appear to be rays of light but on closer inspection prove to be lines made up of music notes), skyscrapers rise behind her while airplanes and zeppelins fly above.

Orphaned at an early age, Dragonette threw herself into her singing. She studied voice at the Georgian Court Convent and College in Lakewood, New Jersey, and landed several roles in Broadway shows during the early 1920s, proving a natural on stage. But it was on the fast-growing medium of radio that Dragonette found the perfect showcase for her singing. With program directors desperate for talent to fill hours of airtime, she landed a five-year contract with WEAF after only a handful of on-air performances.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/2b/4a2b379d-83fa-482e-9bc4-4e1cb07bc613/jessicadragonetteweb.jpg)

She performed operettas there as Vivian, “The Coca-Cola Girl.” WEAF merged with WJZ to become NBC and Dragonette became the major draw of a series of operettas sponsored by Philco, then the Cities Service Concert Series, vastly expanding her audience with each move. Fan letters and accolades poured in and when Radio Guide Magazine asked readers to vote on the “Queen of Radio,” Dragonette won in a landslide.

The World of Radio, created at the height of Dragonette’s popularity, was commissioned as a gift for the singer from her sister and manager, Nadea Dragonette Loftus. It is a celebration of the singer, but specifically a celebration of her career in radio and her role as a pioneer of radio celebrity. Every inch of the canvas not occupied by Dragonette herself is full of depictions of individuals like Giulio Marconi, inventor of the long-distance radio transmission; Richard Byrd, explorer who was the first to reach the South Pole, and broadcasted from there; and zeppelins, airplanes, skyscrapers and NBC microphones.

“I find this work masterful for Smith’s sheer ambition in undertaking such a large and complex composition,” says Randall. “The amount of detail is especially impressive—I see something new each time I look at it…Its design becomes a densely packed stage expressing the vitality of the period.”

On view this year through September 24, the exhibit complements the upcoming and much-anticipated show, “The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s,” which the Cooper Hewitt debuts on on April 7. Showcasing the artistic and social shifts taking place during this decade, “Jazz Age”. While The World of Radio would seem like a fitting piece for this exhibition (considering radio’s development during the 1920s), since the work itself wasn’t completed until 1934, the museum’s team decided to show it as a separate exhibition.

“It’s worthy of its own spotlight as an important piece,” says Randall. “It’s entirely unique and there’s so much happening in it.”

The work displays an optimism and excitement about progress and the changes at hand in the era: “The vignettes in the mural celebrate her career and achievements, and recognize and celebrate the modern age, technology, progress and faith in our future,” says Randall, pointing to the artist’s depiction of allegorical figures representing drama, industry, agriculture, as if they are carved into stone—reflecting their enduring importance and strength. “These allegorical figures provide a very positive view of the future, despite the depression and all the other things going on in the country at the time.”

In this way, the mural itself, while being about the larger cultural impact of radio and the era, “is a highly personal tribute to her,” as Randall puts it. Dragonette’s popularity on radio would fall off as public tastes shifted, but she found great success performing concerts across the country before settling down and focusing on her family and Roman Catholic faith. All the while, The World of Radio hung in her New York City apartment, seen only by those who paid the great singer a visit.

It’s a rare public showing for the piece. The mural has only been displayed a handful of times, most recently at the Cooper Hewitt in 1978, as part of an exhibit of commissioned works titled Look Again. But while much is known about the singer in the center of the work and her sister, not much can be found about the artist himself.

Arthur Gordon Smith was a Canadian, born in 1901, whose work tended to focus on religious and medieval art. In her research, Randall could find only limited information on the artist—that he apparently worked with his brother Lawrence in the 1920s creating batik murals with medieval themes, including one titled Story of Faith. In 1929, he painted 14-foot religious murals on the interior walls of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Springfield, Masachusettes.

But The World of Radio, with its modern imagery and focus on a figure of popular culture, was an unusual work for him.

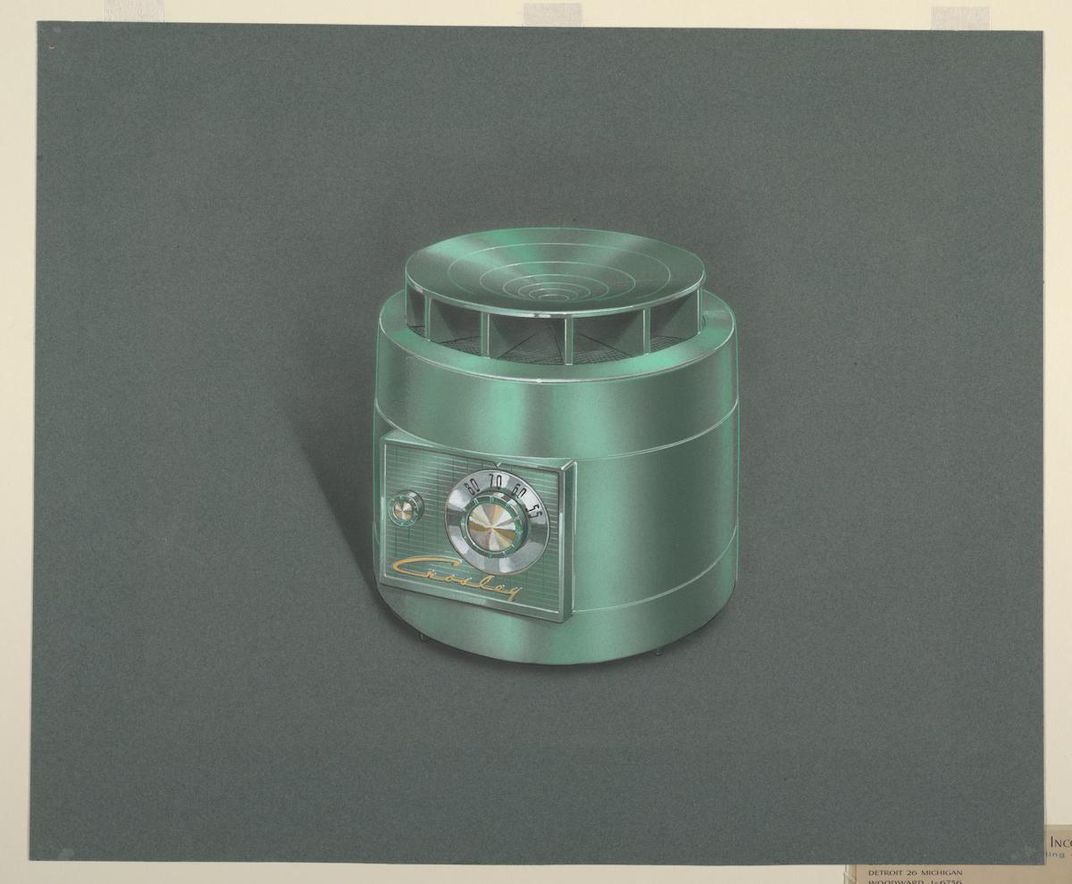

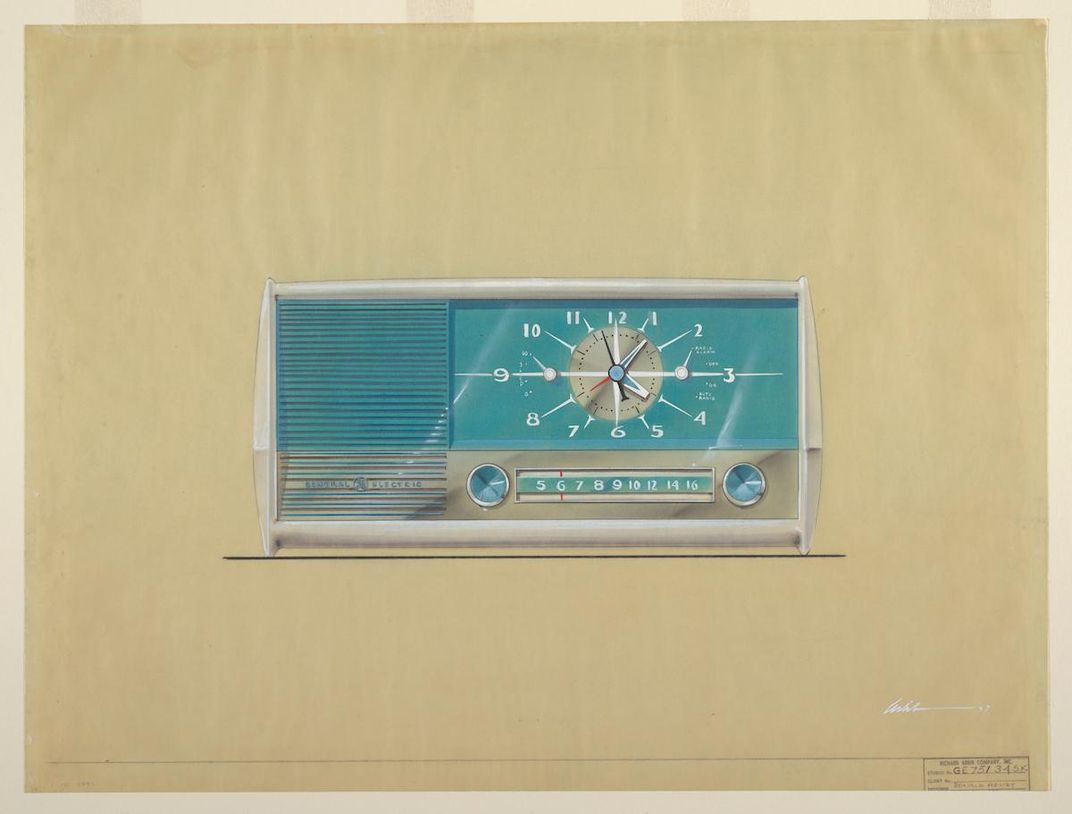

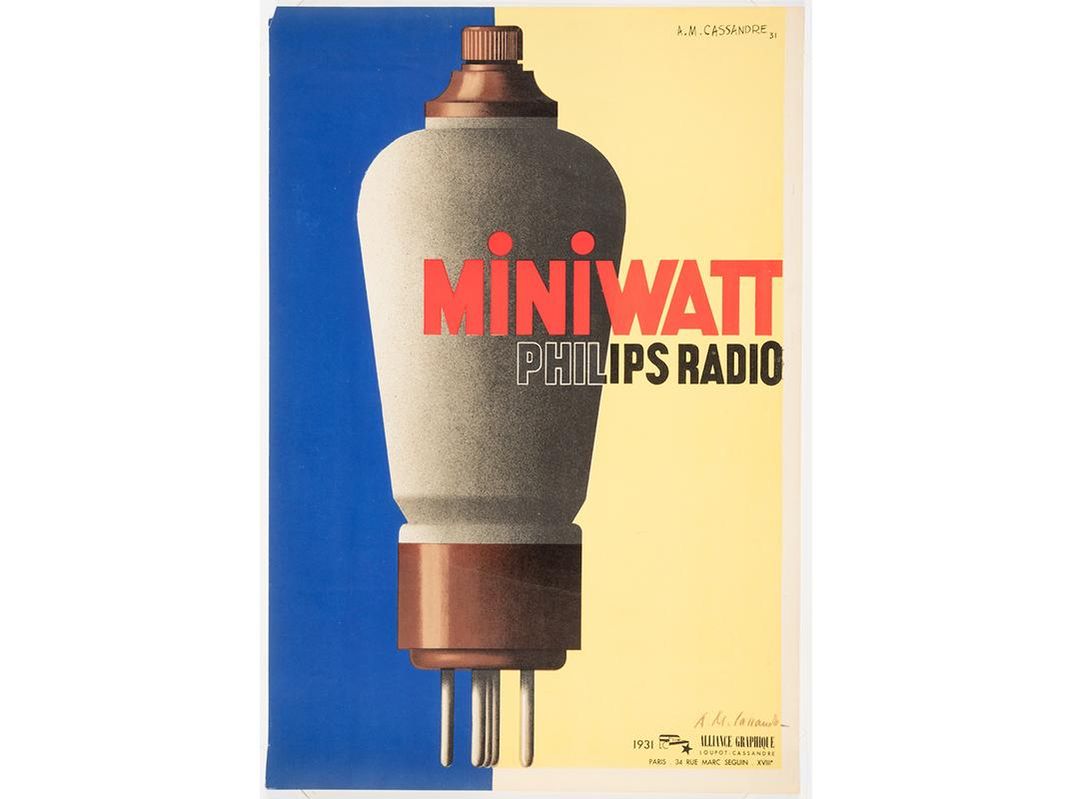

The mural is exhibited in a gallery with works on paper, designs and photographs of the interior of homes to show how radios were incorporated into domestic environments. It also features physical radios spanning eight decades. These include radio cabinets of the 1930s, clock radios in the 1950s and the development of the transistor, to more recent models.

“In the 1980s, interesting things are being done with plastics, and the external aesthetics become more important than what’s inside,” says Randall. “One of the latest radios in the exhibit is from 2009—an iPod nano that had an FM tuner in it, which opens up questions about what makes a radio today, as we have apps that stream music and can make our own playlists.”

"The World of Radio" is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City through September 24, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)