Playful Artworks at the Hirshhorn Get the Better of One Mystified Observer

A group of international mid-century artists built a number of kinetic experiments into their abstract art

It may be the only artwork keeping office hours.

A sign near François Morellet’s 1965 sculpture Wave Motion Thread on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., advises: “This work runs for five minutes and rests for 10 minutes.”

At rest, it certainly doesn’t look like much. Just a long, thin thread hanging from a mechanical box, looking more like a curtain pull mechanism separated from the drapery fabric and the window. Then, as an observer wanders the gallery taking in other futuristic pieces drawn from the permanent collection in the current show, “Le Onde: Waves of Italian Influence, 1914-1971,” suddenly, the artwork comes to life.

A little whir, a hum of electric industry and a tiny wheel stirs the sleeping thread, anchored at the bottom by a plummet, hanging an inch or so above the gallery floor. The mechanical movement transforms what was once a mundane straight line into a series of sine waves up and down the wall, bowing out enough at times to seemingly transform the thread to ribbon.

The waves made by the kinetic sculpture are ethereal, though, nonpermanent—designs made by motion and our own optical systems; the same kind of shapes in air made by lariats spun overhead or speedy schoolyard jump ropes.

Yet this one, done with a decidedly simple little engine shows how the waves could exist without a human spinning a rope. Or would it? Without our eyes retaining the string’s motion and transforming it into shapes as it registers in our brain, would it make the same pattern?

This may recall the philosophical thought experiment: If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it does it make a sound?

But nature would be the furthest thing from the mind of Morellet and others in the art movement known as GRAV. The name — it stood for Groupe de Recherché d’Art Visuel, or Group for Research in Visual Art — made them sound more like white-coated scientists than artists.

But the international group of artists founded in Paris in 1960 put on a number of kinetic experiments in abstraction that tried to reflect the space age as defined by new scientific discoveries.

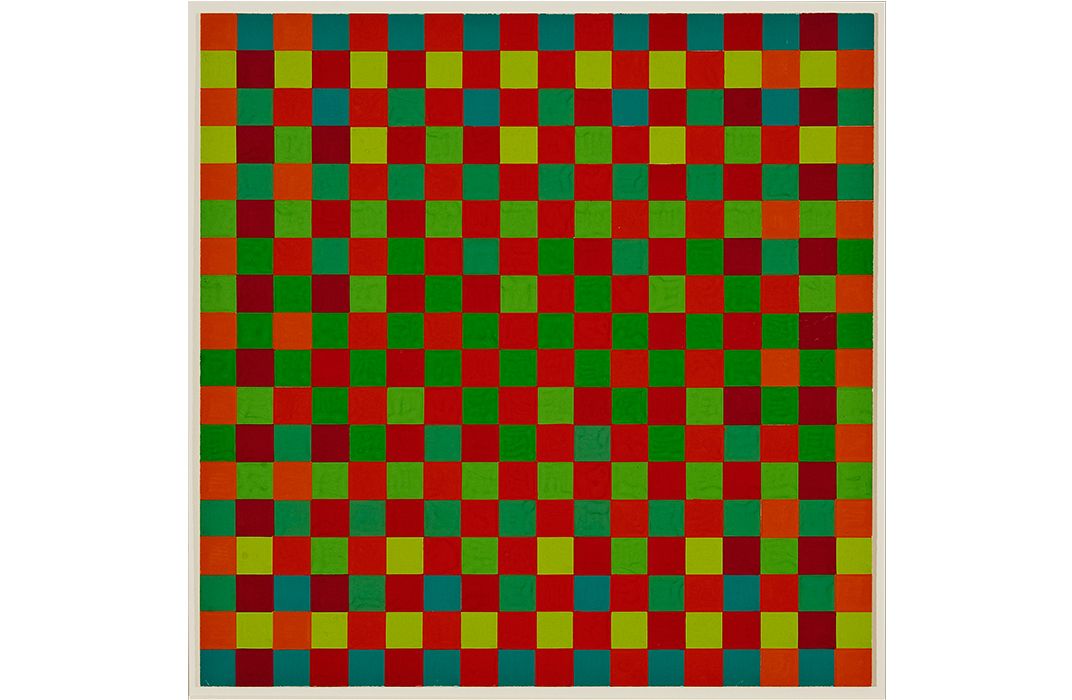

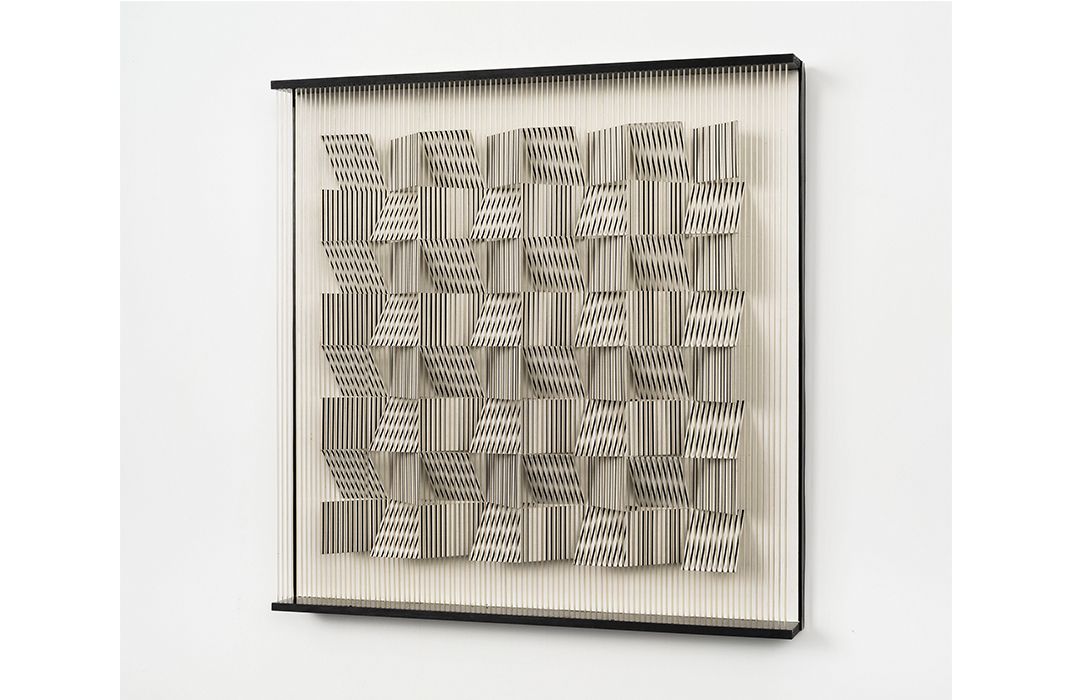

Morellet’s Wave Motion Thread is at the forefront of the movement, but the buzzing lines in Horacio Garcia-Rossi’s 1962 checkered pattern Vibration No. 2 that is also on display, provides it without a motor.

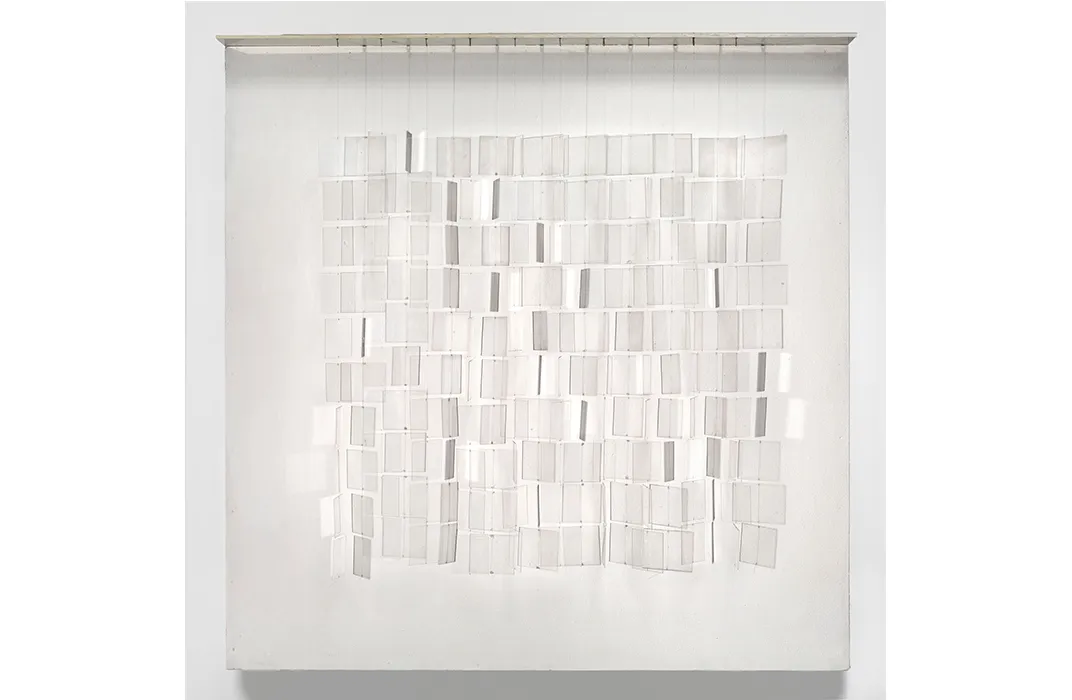

There seem to be fireflies of light surrounding a third piece, Julio Le Parc’s Determinism and Indeterminism from 1960-1963. It’s as if someone has installed a mirrored disco ball in a discreet corner. But no. They are merely reflections from the individual squares of plexiglass, affixed by strings that allow them to freely dangle and move according to the whim of interior air, bouncing back the light.

And yet, according to the Hirshhorn’s Mika Yoshitake, who curated the show, these later GRAV artists weren’t fearful of the frenzy that modernization and industrialization brought. Rather, their work “reflected the streamlined order of the technological age,” she says in the show catalog, noting particularly that Morellet’s piece “reveals the presence of natural forces acting in the gallery with hypnotic effect.”

GRAV had its roots in the work of Italian Futurists like Giacomo Balla, whose Sculptural Construction of Noise and Speed a century ago “attempted to mimic the kinetic energy of industrial technology,” Yoshitake says.

It is rendered in aluminum and steel in its 1968 replication, obtained by museum founder Joseph Hirshhorn.

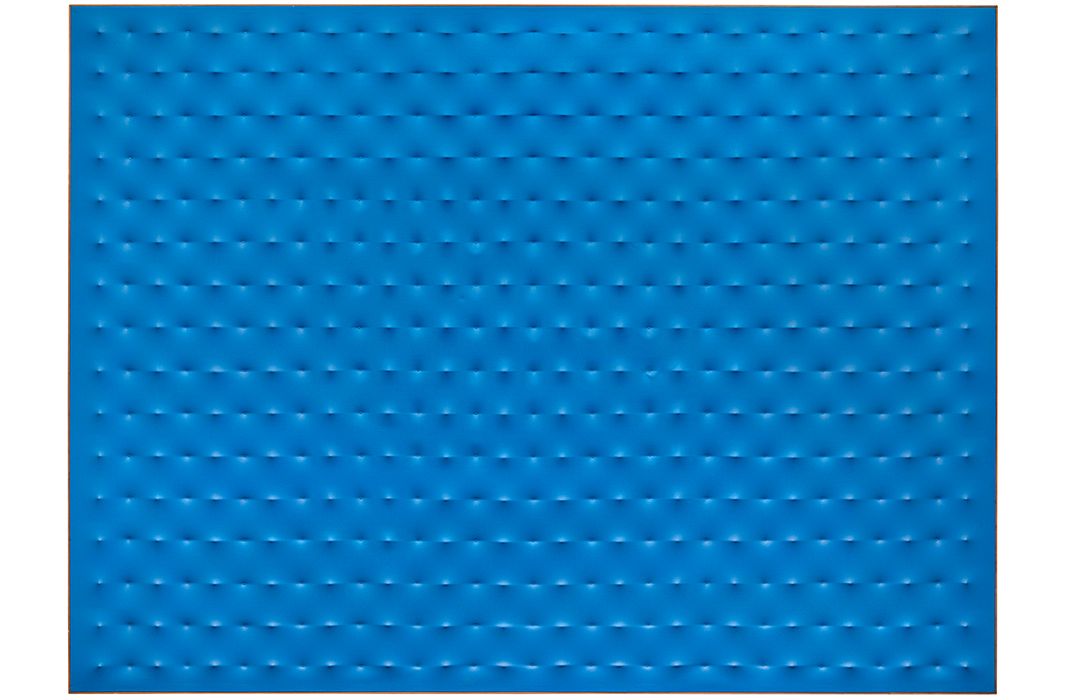

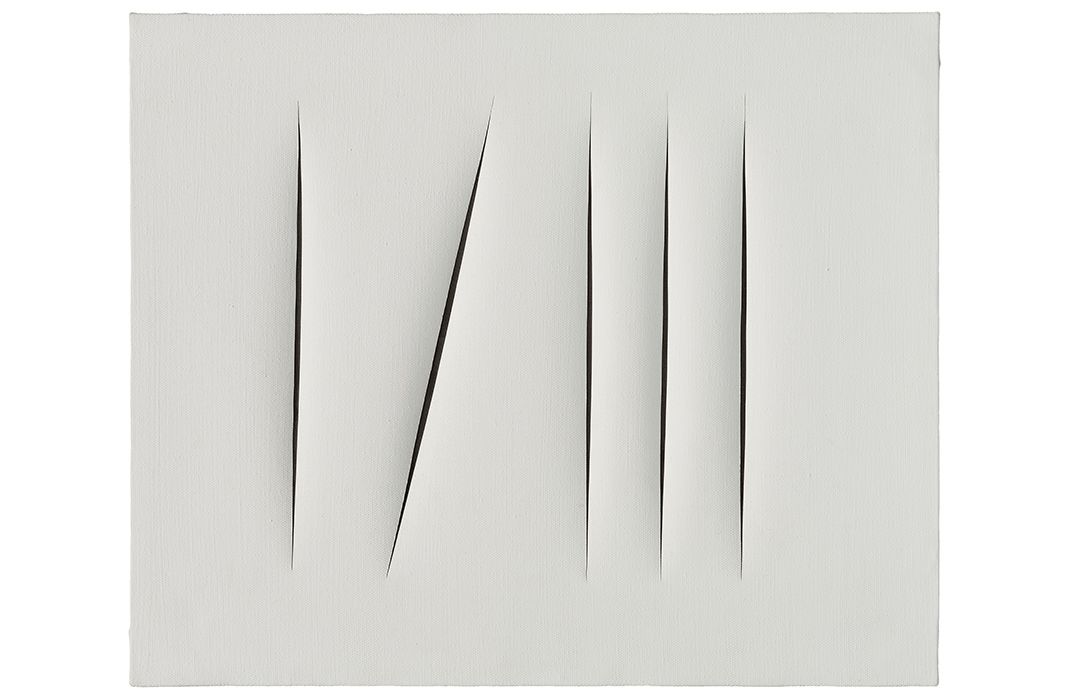

Another strong influence among this set of artists was Lucio Fontana, born in Argentina of Italian parents, whose ideas of slashing canvases or driving holes in them affected artists on two continents, inspiring artists like Giò Pomodoro and Enrico Castellani, who further altered picture planes by making it appear as if something was going to burst through from the other side (In the 1968 Opposition, perhaps a person).

Fontana’s biggest influence, however, may have come after the Manifiesto Spaziale (spatialist manifesto) and the Manifiesto Blanco published by a group of artists in the 1940s in Buenos Aires and urging that the speed and energy of the age be reflected in art. The movement called for new modes of media to reflect immaterial elements of light, time, space and movement.

“We do not intend to abolish art or stop life; we want paintings to come out of their frames, and sculptures from under their glass case,” Fontana said. “To this end, using modern techniques, we will make artificial forms, marvelous rainbows, luminous words appear in the sky.”

Nearly 20 years later, he looked back and said his manifesto “intuitively identified the reason for art in the space age and the new dimension of man in the universe.”

The exhibition, which continues through January 3, 2016, also includes works by Carlo Battaglia, Giò Pomodoro and Yvaral, as well as sculptures by Brazilian artist Sérgio de Camargo, a student of Fontana, and Heinz Mack. Many of the artifacts in “Le Onde,” have not been seen on display since the museum was first opened. One of the most recent works in the exhibition, organized with support from the Embassy of Italy in U.S., is a piece by Giovanni Anselmo called Invisible.

The 1971 work, like the Morellet, involves electricity. And yet it’s not immediately clear what it shows. There’s a projector on, beaming something somewhere. But what, and where? It is not immediately clear.

Is it just that it’s invisible, living up to the title?

The observer approaches the projector, not unlike a frustrated lecturer with a malfunctioning slideshow. Then suddenly, it reveals itself, projecting the Italian word “Visibile” onto a viewer — providing the observer is a couple of feet from the beam. (Although such an action is counterintuitive in a culture where one learns to duck out of a projected beam just to be polite).

Not only does it require to be plugged in, but also like the Morellet, it requires a willing participant to complete it.

But unlike the Morellet, it doesn’t take 10-minute breaks.

“Le Onde: Waves of Italian Influence, 1914-1971” continues through Jan. 3 at the Hirschhorn Museum, 700 Independence Ave SW, Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)