Orchidelirium, an Obsession with Orchids, Has Lasted for Centuries

The once-elusive flower’s striking beauty has inspired collectors and scientists to make it more accessible

Orchids have long been the subject of intense scientific interest and at times, emotional obsession. "When a man falls in love with orchids, he'll do anything to possess the one he wants. It's like chasing a green-eyed woman or taking cocaine. . . it's a sort of madness," proclaims an orchid hunter in Susan Orlean’s bestselling book The Orchid Thief. This level of devotion has inspired significant investment in the flower throughout history, even motivating scientific breakthroughs that have made the once-elusive bloom plentiful and affordable enough for the everyday person.

Prior to advances in the last century, however, orchids were exclusively the purview of the elite. During the 1800s, a fascination for collecting the flowers erupted into hysteria. The craze, dubbed "orchidelirium," produced prices in the thousands of dollars. Special hunters were employed to track down exotic varieties in the wild and bring them to collectors, keen to display them in ornate, private greenhouses.

"Back in those days," says the Smithsonian's orchid specialist Tom Mirenda and curator of a new show that opened this week at the National Museum of Natural History, "orchids were for the rich, even royalty." Orchids in the wild, he says, were seen as "one-of-a-kind, true rarities."

Before modern technology, the only way to get such a plant was to wait as much as a decade for it to be large enough to divide. "Such a division could cost thousands," he says, adding that among the first technologies used in the Victorian era to grow and nurture orchids were Wardian cases, decorative sealed glass and frame containers that kept delicate plants alive in artificial tropical environments, allowing for the transportation of exotic orchids over long ocean voyages.

Today, says Mirenda, orchid collecting is a far more egalitarian pursuit, thanks to significantly improved reproduction and propagation technology, including cloning.

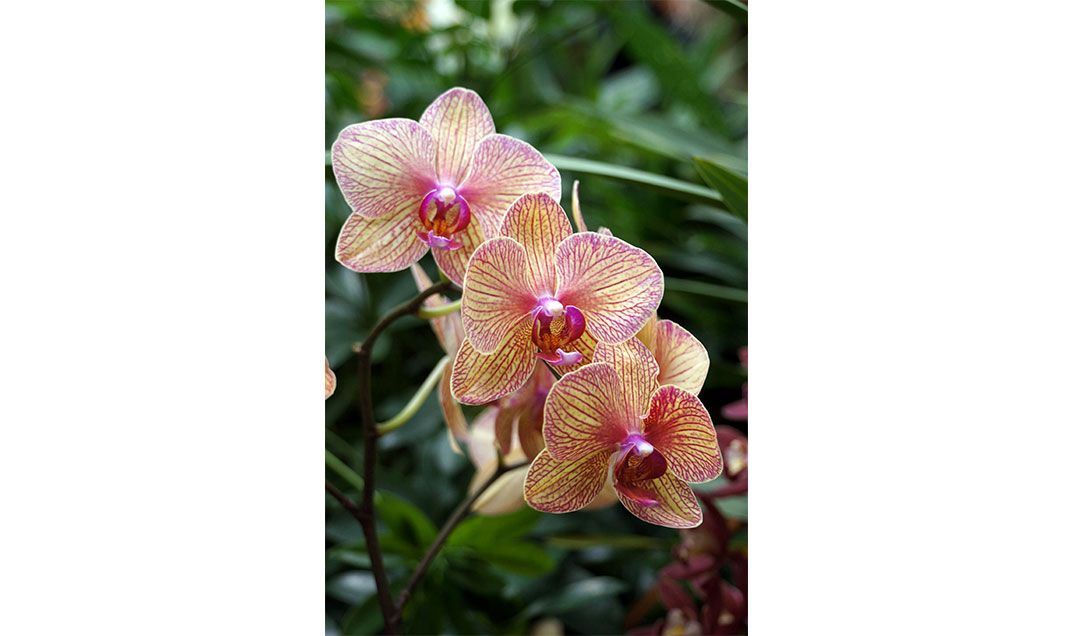

"The orchids we buy in stores nowadays, are clones, or mericlones, and they are actually the cream of the crop," he says. Selected for their superior colors and shapes, they are cloned through very inexpensive tissue culture techniques.

Mirenda notes that the Moth orchid, or Phalaenopsis, one of the most prevalent varieties on the market, has outpaced sales of the poinsettia. “There’s something very appealing about these flowers to the human psyche,” he says, adding that they have been bred to reflect nearly every color and pattern.

Mirenda attributes this the orchid’s bilateral symmetry. “You look at an orchid, and it looks back at you,” he says. "They seem to have a face, like a human."

Orchids, says Mirenda, have also evolved in their appearance, to have patterns and designs that mimick other organisms, including flowers and insects, as a means to deceive their predators.

Scientific breakthroughs on the beguiling plants continue. Present-day research on the flower reveals new ways to breed innovative varieties including a genetically blue orchid, which is an extremely rare color for the plant, and Mirenda says he's heard rumor that a breeder is trying to integrate a squid’s glow-in-the-dark gene into an orchid.

DNA sequencing of different orchid species (there are more than 25,000) has also enabled botanists to determine unexpected relationships between orchids and other plant types, as well as to discover never-before-classified fungi that have a symbiotic relationship with the flower. These findings will be important to help nurture orchids in the wild that are struggling to survive and impact the next phase of innovation related to the flower, insuring that it continues to thrive.

Although they may no longer be quite as rare, the fascination with the bewitching flower lives on.

The 20th annual orchid exhibition entitled "Orchids: Interlocking Science and Beauty" is on view through April 26, 2015 at the National Museum of Natural History. Featuring orchids from the Smithsonian Gardens Orchid Collection and the United States Botanic Garden Orchid Collection, the new exhibition explores the story of science and technology of orchids throughout history, "from new world to old world." A wall of cloned orchids, along with a 3D-printed orchid model is on display to illustrate these developments.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/1f/0d1f920b-a474-4530-85ee-ef250f888b7c/paphiopedilum-baldet-atlasweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)