One Man’s Trash is Brian Jungen’s Treasure

Transforming everyday items into Native American artwork, Jungen bridges the gap between indigenous and mass cultures

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Brian-Jungen-631.jpg)

Brian Jungen wanted to get out of his Vancouver studio and spend some time outdoors. In April 2008, he headed for Australia and pitched camp on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbor. There, as he gazed upward, two things caught his eye: the night sky, filled with constellations unlike any he had seen in the Northern Hemisphere, and the steady traffic of airplanes. "The island was directly in line with Sydney International Airport," he recalls.

With astronomy and air travel on his mind, he bought and tore apart luggage to create sculptures inspired by the animals that Australia's indigenous aborigines saw in constellations—including an alligator with a spine fashioned from the handles of carry-on bags and a shark boasting a fin sculpted from the gray exterior of a Samsonite suitcase. Two months later, the menagerie was hanging from a 26- by 20-foot mobile, Crux, at Australia's contemporary arts festival.

There's an old belief, shared by many cultures, that a sculpture is hidden within a block of uncut stone, just waiting for an artist to reveal it. Jungen, 39, likely would agree: the half-Dunne-za (a Canadian Indian tribe), half-Swiss installation artist has a gift for seeing images in mundane objects. "When a product breaks, it's kind of liberated in my eyes," says Jungen. In 1997, when the Dunne-za chief council began distributing funds from a land claims settlement among tribal members, the artist noticed that some of them were using the money to buy leather couches. "I thought it was this crazy icon of wealth," he says. "But there's a lot of hide in them." Jungen dismantled 11 Natuzzi sofas and built a massive tepee with the leather and wood.

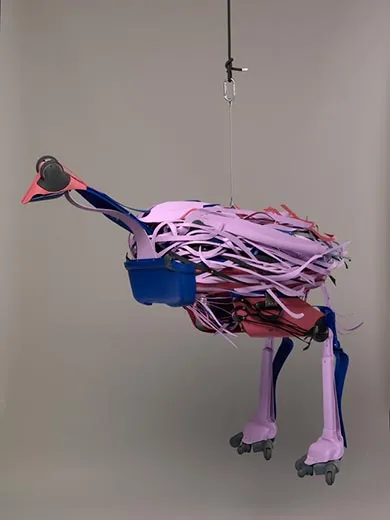

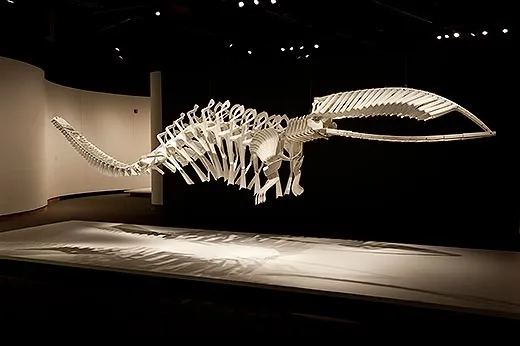

In 2000, Jungen began noticing all the broken white, molded-plastic patio chairs being put out for trash on curbsides. At the time, he says, he was reading about the history of whaling, and "everything kind of clicked." Hence, Shapeshifter (2000), Cetology (2002) and Vienna (2003)—three 21- to 40-foot-long whale skeletons made with plastic "bones" carved out of the chairs. Next month, Jungen will become the first living artist to have a solo exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. "Brian Jungen: Strange Comfort" opens on October 16. (Crux, the centerpiece, will be installed in the Potomac Atrium, the museum's soaring rotunda.)

Sitting in a fifth-floor conference room at the museum wearing a T-shirt, camouflage cargo shorts and Adidas trail runners, Jungen displays a teenage spirit that belies his age. It's as if his surname, which translates to "youth" in Swiss German, is prophetic—right down to his subtle mohawk hairstyle and timid smile that reveals braces on his teeth.

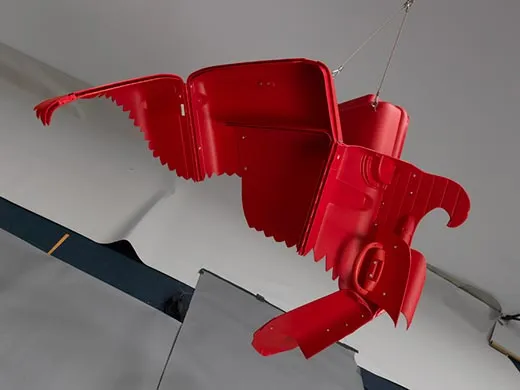

Jungen considers his work a "return to the use of whatever a Native American artist has at his disposal." He credits his Dunne-za side of the family for his resourcefulness. As a kid in northeastern British Columbia, he'd watch his relatives recycle different household objects to extend their usefulness. In his early years, he dabbled in just about every artistic medium. Then, on a 1998 visit to New York City, Jungen saw some red, white and black Nike Air Jordan basketball shoes in a store window. They were the traditional colors of the Haida, an indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest coast. Meticulously restitching the shoes into ceremonial masks, the "wizardly craftsman," as New York Times art critic Grace Glueck called him, fashioned shoe tongues into curled ears, reinforced toes into chins and Nike swooshes into eyes.

Jungen gravitates toward such items because he's interested in the way professional sports fill the need for ceremony within the larger culture of society. In doing so, say the critics, he bridges the gap between indigenous and mass cultures.

NMAI curator Paul Chaat Smith agrees. "He's found a way to talk about an Indian experience using new materials and new ideas in a way that opens up a space for a lot of artists, native and otherwise," says Smith.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)