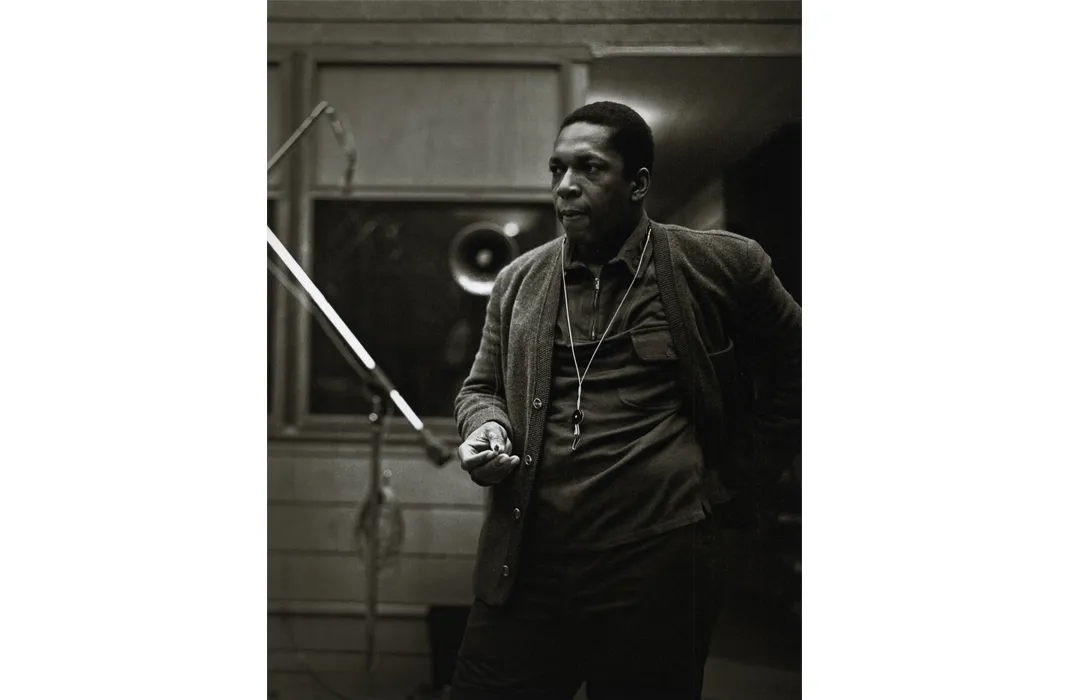

New Photos of John Coltrane Rediscovered 50 Years After They Were Shot

During the recording of A Love Supreme in 1964, Chuck Stewart caught the jazz legend in his element

On December 9, 1964, saxophonist John Coltrane led a quartet that featured pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison into Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, where countless jazz recording sessions were held in the 1950s and ’60s. For photographer Chuck Stewart, Van Gelder’s was a short drive from his home in Teaneck.

That day nearly 50 years ago the band recorded a Coltrane composition titled A Love Supreme, a profound expression of his spiritual awakening divided into four movements—“Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” “Psalm.” For its soaring ambition, flawless execution and raw power, it was hailed as a groundbreaking piece of music when it was released in February 1965, and it has endured as a seminal part of the jazz canon. The work and its composer will be highlighted anew this April during Jazz Appreciation Month, an annual event launched in 2001 by the National Museum of American History, whose collection includes Coltrane’s original manuscript for A Love Supreme.

For Stewart, whose photographs have graced thousands of album covers, from Ellington to Davis, from Basie to Armstrong, that session with Coltrane—a friend of his since 1949—was no different from countless others. “When I did a session I would go in and shoot the rehearsal before they did any takes,” the 86-year-old photographer recalls, sitting in his cozy, picture-filled living room in Teaneck. “I couldn’t shoot during the take because the recording equipment would pick up the clicks. So what I did was meander around the studio. When I saw a picture I thought worked, I’d take it.”

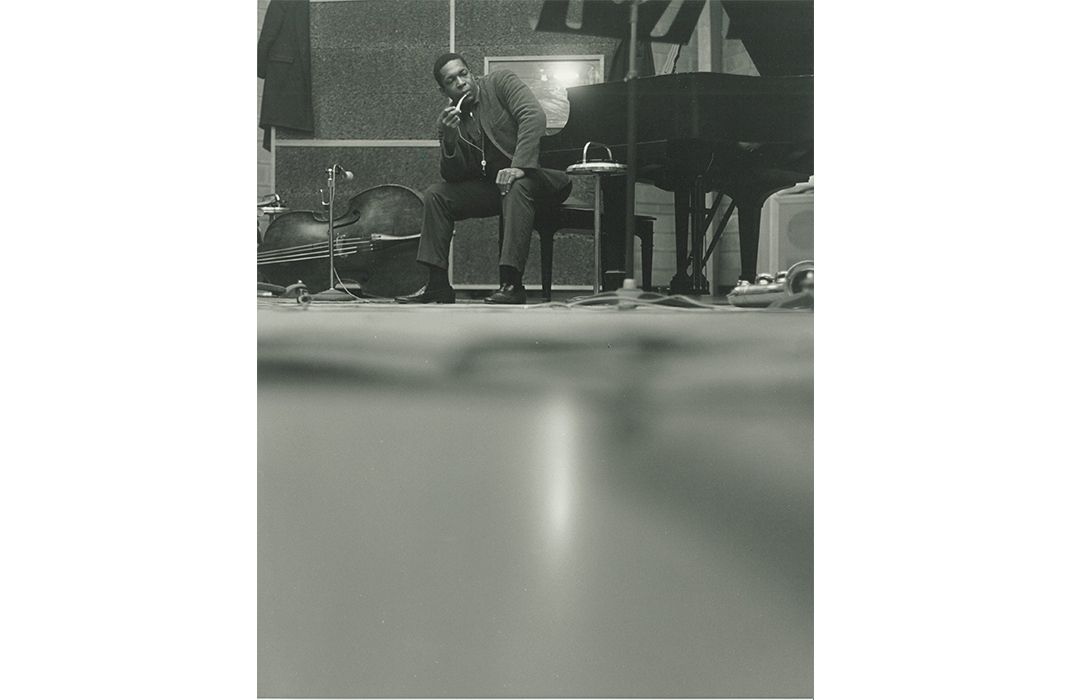

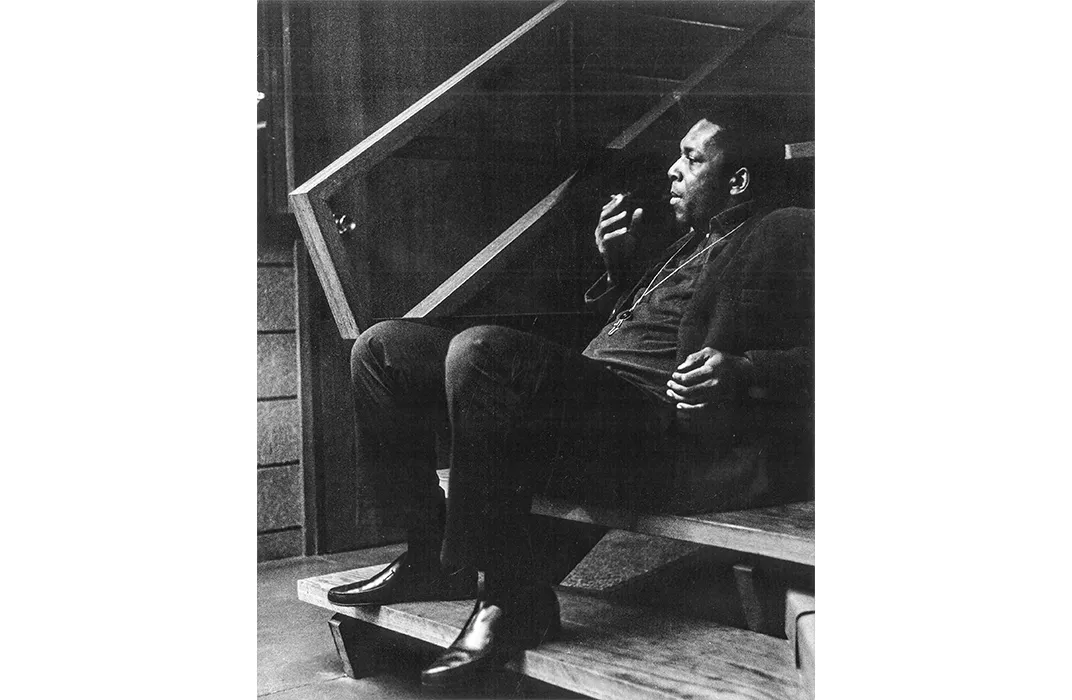

Stewart still has the Rolleiflex camera he used at the session, and the contact sheets as well. Many of the images he shot have been seen on CDs, as well as in numerous books and magazine articles. But 72 photographs from six rolls of film never made it beyond the contact-sheet stage, and so haven’t been published. Stewart’s son David recently rediscovered those images in his father’s collection, and now Stewart is scheduled to include some of them in a donation to the museum this month.

Looking over the contact sheets from those rolls, Stewart picks out two favorites. One finds Coltrane reclining on a staircase and talking with someone in the studio. The other, taken from a distance, shows him sitting at a piano, lost in thought. “I was looking for a decisive moment,” recalls Stewart.

The photographer is reluctant to offer assessments of Coltrane’s music, but after some prodding, he allows that A Love Supreme was part “of a long spiritual evolution” for the musician that would be aided by his marriage in 1966 to pianist Alice McLeod, who would later lead an ashram in California. When pressed further to describe what he heard that day, Stewart smiles and says, “That’s not something I can really answer. I took piano lessons for eight years, and when I was through I couldn’t even play ‘Chopsticks.’” Then he adds, “John was basically a musical genius. What he did was learn how far the musical instrument he was playing could go, and he took it further than any tenor saxophone player in history.”

Of the band, he says, “Everyone had a very high regard for John, and they knew what was expected of them and they functioned accordingly. He wasn’t a bossy type, but he was the boss of his sessions, no question.”

Though Stewart’s photographs would be widely used in books and articles connected with A Love Supreme, it is not a photo of his on the cover of the original Impulse album—and that remains a sore subject for him all these years later. “That photo is by [album producer] Bob Thiele,” he says. “It was a picture he’d taken at a session and he put it on there. I expressed my disapproval.” He pauses and adds, “I cursed him out.”

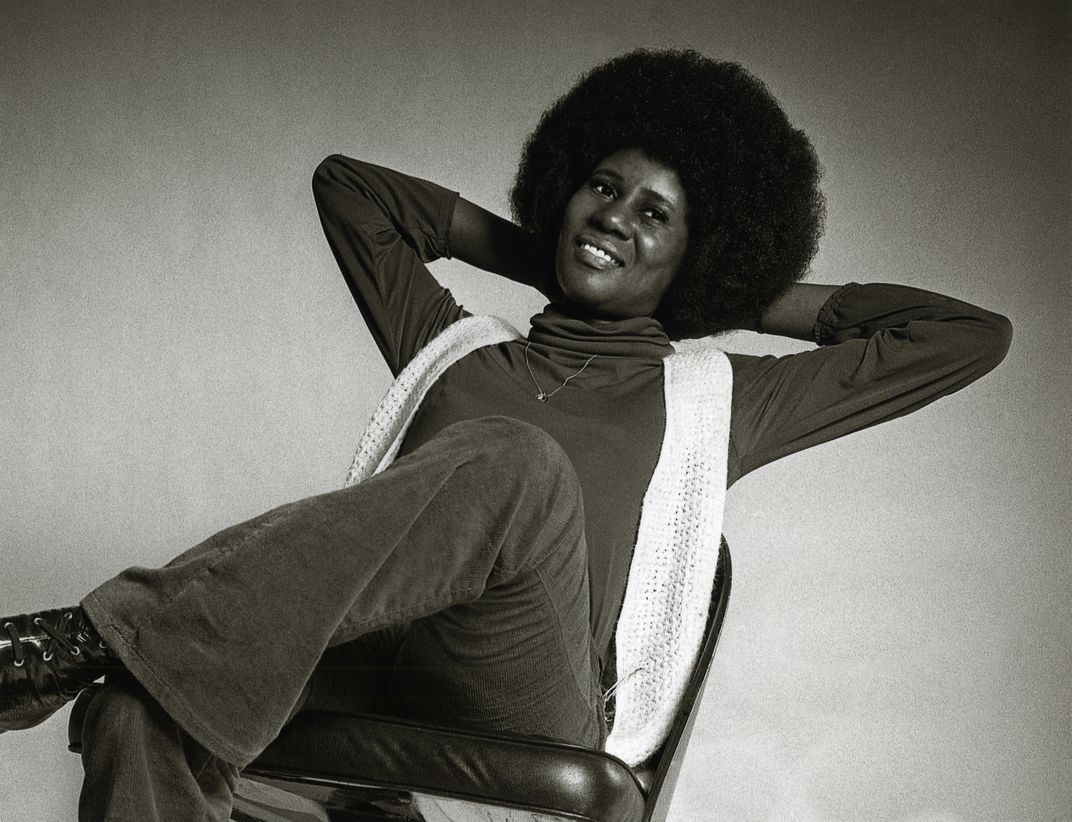

UPDATE: On March 26, 2014, photographer Chuck Stewart donated 25 images, featuring John Coltrane, his wife Alice Coltrane and his band members McCoy Tyner, Archie Shepp and Bob Thiele, to the collections of the National Museum of American History.