Natalie Portman’s “Jackie” Reminds Us Why JFK’s Assassination Became Our National Tragedy

A Smithsonian scholar revisits those critical decisions Jacqueline Kennedy made following the death of her husband

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/27/3f270cee-93ee-4e76-9803-22332b71d179/pablo2web.jpg)

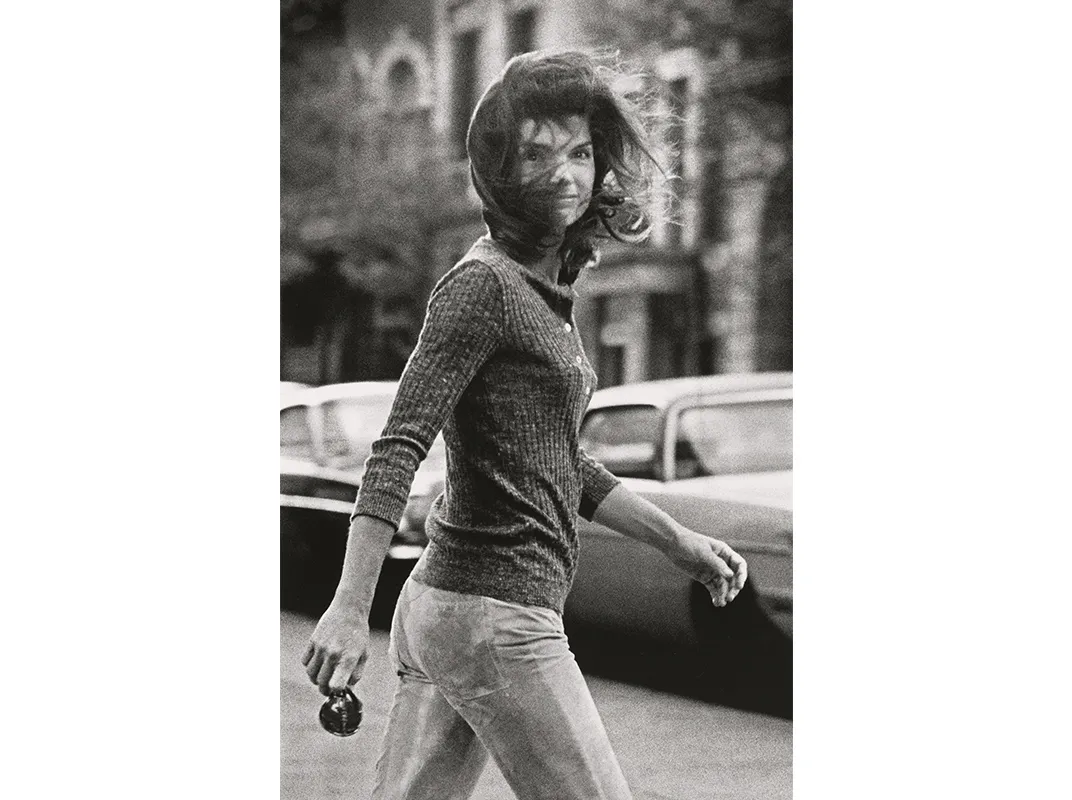

The assassination of John F. Kennedy in November of 1963 forged a long-standing American nostalgia for a president, his brother, and everything that surrounded him—including, and perhaps especially, his widow.

Americans continue to relive that indelible moment, endlessly exploring its significance and consequences. Most recent among the pantheon of Kennedy narratives is the new film Jackie starring Natalie Portman and directed by Pablo Larraín that narrates how Jacqueline Kennedy handled her duties as First Lady and how she framed her husband’s legacy.

Placing moviegoers directly into the milieu and aftermath of the assassination, the film Jackie asks big questions about life and death and the significance to survivors of such trauma. The historical Jacqueline Kennedy somehow arrived at an intense reckoning in a stunningly brief amount of time. No intellectual slouch, the young widow calculated how to create an enduring legacy for her husband, whose handsome charm, some would argue, may have been his only contribution as President.

Yet today, John F. Kennedy remains revered, even idolized, as one of the great American presidents. The film argues that the cementing of this reverence was in no small part accomplished by the transformative hardening of Mrs. Kennedy’s iron will.

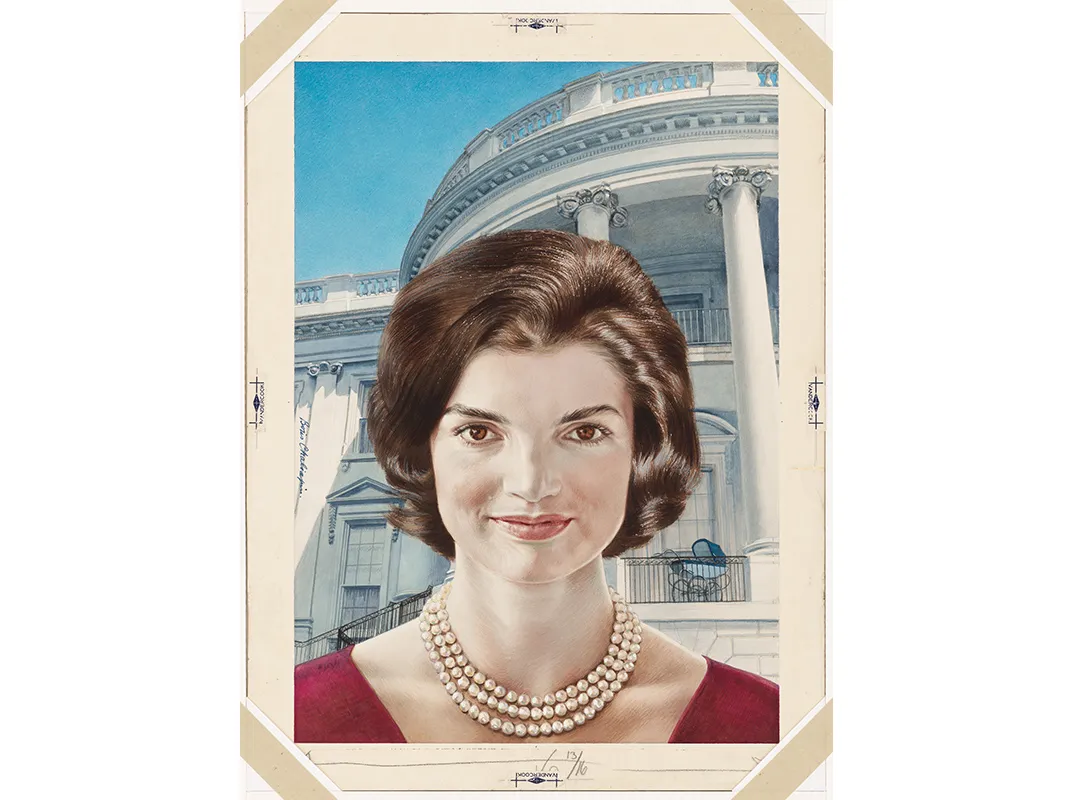

The film recalls the hostile press scrutiny the First Lady faced after the 1961-1962 White House restoration, mostly for having spent $2 million in the endeavor—more than $15 million in today's dollars.

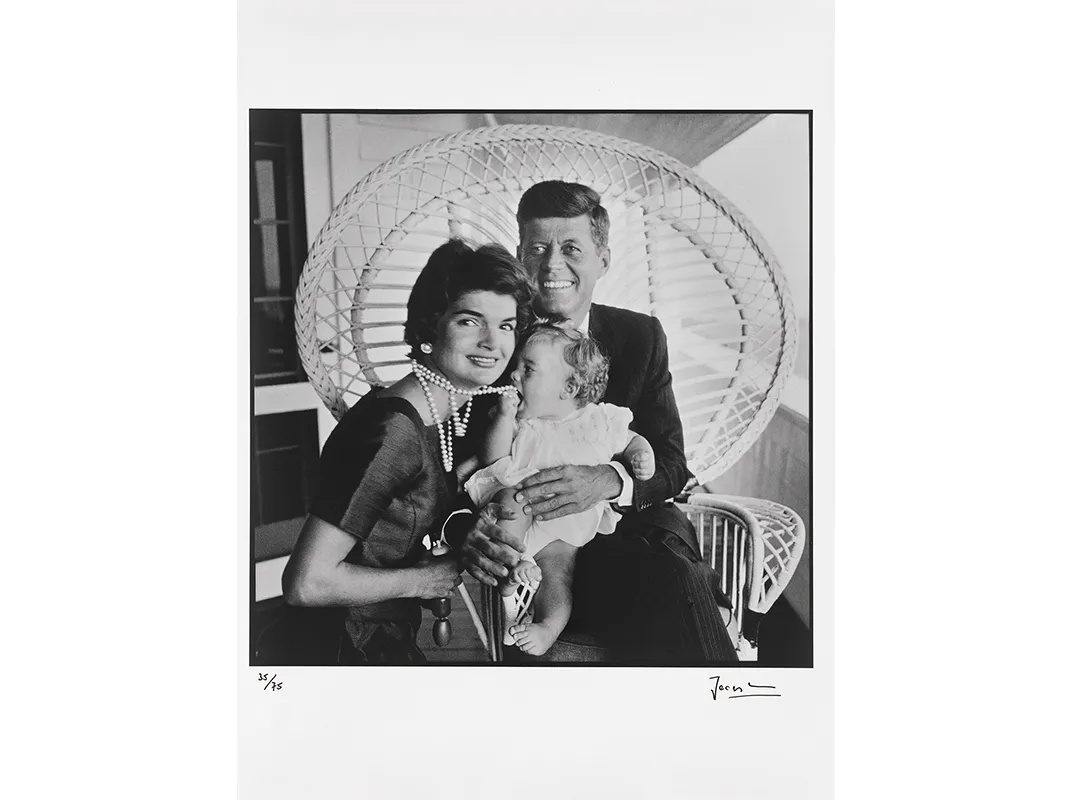

Her study of the furniture and material culture kept by the households of previous presidents became her best primer in understanding the legacy of the office—a kind of prism through which history could be viewed. These lessons were especially important immediately following the traumatic witnessing of the violent death of her husband. The shock would have shattered most people.

Instead, Jacqueline Kennedy, although visibly shaken, remained remarkably collected. In part, this is because she had studied the history of Mary Todd Lincoln.

In order to finance her relocation to Illinois following her own husband’s assassination, Mrs. Lincoln was forced to sell her furniture and other belongings. In 1962 as part of the White House restoration efforts, Jacqueline Kennedy tracked down the Lincoln household artifacts and attempted to bring them back to the White House. Mrs. Kennedy could never have imagined how, in an ironic and cruel twist of fate, she herself would leave the White House in 1963, following the assassination of her own husband.

In spite of the obvious cause of the president’s death, by law, an autopsy had to be performed. In the film, a weary and desperate Jackie could not prevent the cutting open of the body and the examination of it.

Portman's performance delivers on this crucial metamorphosis when the First Lady realizes that all decisions have to be masterminded, with an almost methodic calculation to assure her husband’s legacy—and by extension, her own future.

To get her way, Portman well conveys the moment when Jackie assigns herself a powerful male ally, her brother-in-law Robert F. “Bobby” Kennedy. As she and Bobby accompany the dead body back to her residence at the White House, Jackie asks the driver a series of questions. Did he know how Presidents Garfield and McKinley died? The answer is an emphatic “no.” What does he know about Lincoln? “He freed the slaves,” the driver replies. Jackie nods.

Lincoln’s presidency—which historians today understand as one of the greatest—was well remembered by the American public, even a century later. In contrast to Lincoln, nothing was known about the deaths of McKinley or Garfield—both by assassination. Garfield’s presidency was relatively short—a mere 200 days—and he struggled to define his executive power during this time. McKinley, on the other hand, achieved great economic expansion and redefined American borders and international influence through the War of 1898.

In the light of history, Jacqueline Kennedy knew that she could play a crucial role in defining the indelible and lasting image of her husband—one that would resonate well with the media, and become the historical record. By modeling her husband’s funeral after that of Abraham Lincoln, Jacqueline Kennedy set in place that legacy. So effective was her staging that it replays annually each November in the media, remembered by artists, by politicians and embedded in the cultural mindset of the American people.

Given the platform for publicity and scrutiny, Jacqueline Kennedy was thrust into a position of power that she probably never expected.

The film’s focus on the monumental decisions she faced begs the question: what kind of role does the First Lady really have?

The murky answer is in part due to the remarkable simplicity of the executive office of the President. Each president defines his own office responsibilities—there are no set directives writ large in the library of American legislature.

Similarly, the First Lady distinguishes her own responsibilities.

The role of First Lady is inevitably wrapped up in gender expectations for women today. Traditionally, she is host to important guests of the state. In a way, she is the top diplomat of the United States. If she has had her own career, like Michelle Obama, she may put it on hold. If she chooses to continue it, like Hillary Clinton, she may face terrible criticism.

Just as the movie portrays Jacqueline Kennedy, the White House itself is a study of survival. Although not a space for frills and luxury, the staid public rooms in the White House today function as dignified keepers of American history. Its structure reveals many episodes of violence and trauma embedded in centuries of fire, bad construction and damaged infrastructure. Yet the house remains standing today, a timeless and distinctively American symbol.

Maybe Jacqueline Kennedy’s idea to use material culture as a prism for history wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lemay-photo.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lemay-photo.png)