Meet Another Side of Alexander Calder at the Portrait Gallery

A new look at the artist whose avant-garde mobiles and stabiles changed and challenged notions of design and space

Forget everything you already know about Alexander Calder. Forget, for a moment, that Alexander Calder is an acclaimed artist whose avant-garde mobiles and stabiles both changed and challenged notions of design and space. Forget the sculptures—colorful geometric patterns bent, shaped and designed in the most imaginative ways—and the paintings, forget those, too.

Now, get ready to meet Calder again, as if for the first time.

In the new exhibition "Calder’s Portraits: A New Language," visitors are introduced to an often overlooked side of Alexander Calder (1898-1976)—that of the prolific portraitist. "This is the first show, 35 years after his death, to really zero in on portraits," says guest curator Barbara Zabel, professor of art history at Connecticut College.

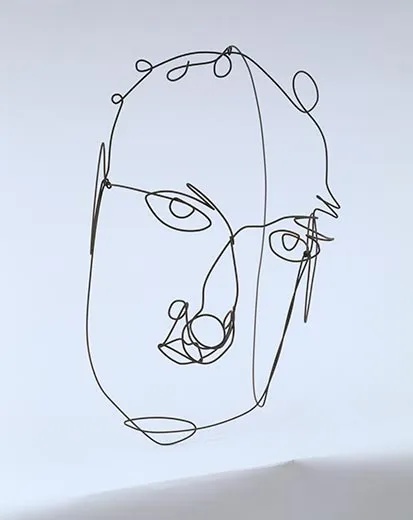

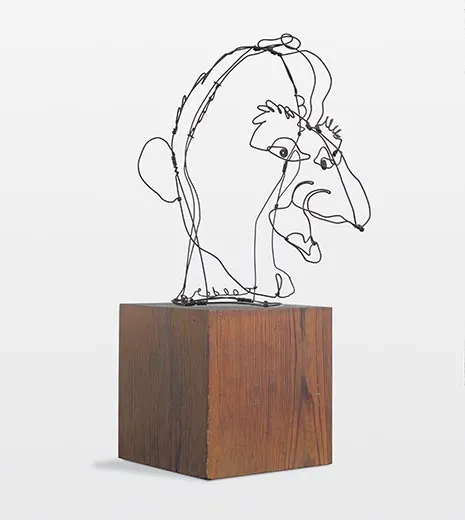

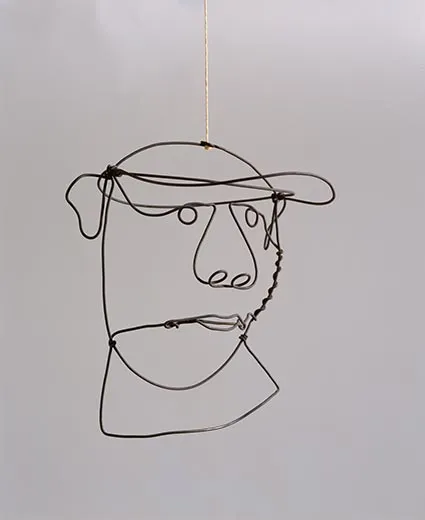

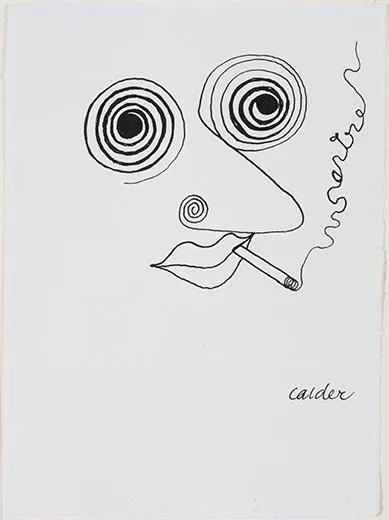

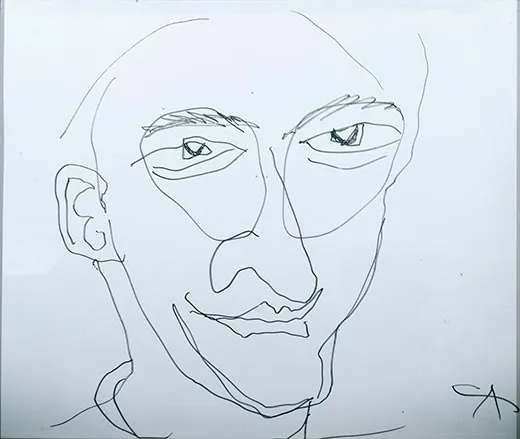

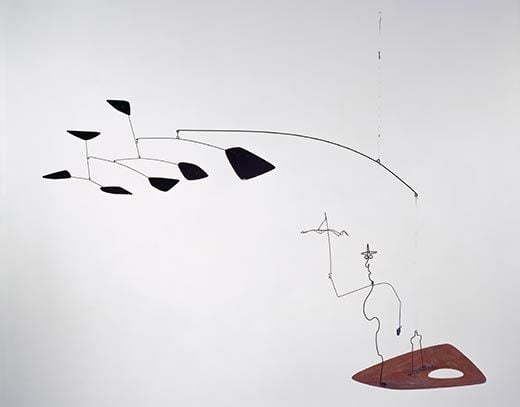

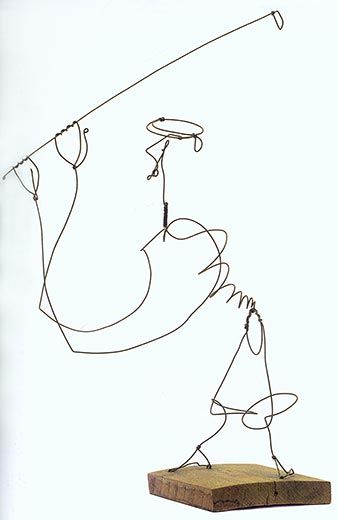

"In Paris, after 1926, Calder starts bending wire into portrait likenesses, drawing in space," Zabel says. And Calder’s portrayal of public figures, entertainers, close friends and himself, are, in typical Calder fashion, like nothing ever imagined. Using bent wire and metal, Calder playfully toes the line between caricature and art during a time, in the 1920s, when there was a fine line, says Zabel.

Trained as a mechanical engineer, Calder’s early life lends clues to the artist he would become. The hallway, which runs the length of the exhibit’s six galleries, features Calder’s self-portraits. The first portrait is of Calder at age nine, seemingly surrounded by tools. "This really sets the stage for the rest of his career," says Zabel, one that would include working in many different mediums—painting, sculpture, watercolor—and with many different materials—metals, wood, Terra cotta, bronze.

This exhibit, Zabel says, gives the Portrait Gallery an opportunity to showcase an overlooked part of Calder’s career, as well as continue exploring ideas of portraiture through the theme of identity, both how we define, construct and change it over time.

"We don’t have innate identity," Zabel says. "Identity isn’t something that we have, but it’s something that’s constructed over time." Nor is identity constructed in isolation, but rather through interaction with others. Calder’s use of wire in his portraits gives viewers the ability to see and reflect on the different aspects of an individual. The portraits, some of which are suspended from the ceiling, moving and playing with the shadows on the wall, seek to illuminate aspects of the subject’s personality, as Calder understood them, not definitely define it.

"Calder called himself an illumination engineer," Zabel says. And his work showcases "facial features in flux," which allude to a life in flux, and even an identity in flux.

The galleries are organized and determined by the identities of the subjects; public figures, entertainers and artists, sports figures and icons, his supporters in the art world and his artist friends. And their inclusion gives clues into the personality of the artist himself. Some galleries are fitting, as Calder was himself was an entertainer, putting on shows in Paris, as well as a jazz aficionado who loved to dance and spend time with friends. But the inclusion of other galleries, like "Sports Fans and Icons," are curious, as Calder was nether a sports enthusiast, nor a competent athlete.

Not every subject was pleased with Calder’s wire depictions. One of his subjects, Erhard Weyhe, a New York gallery owner known for a stern demeanor, was not amused by Calder's stark, minimalist approach. But Calder’s work, even his choice of wire—perhaps alluding to his feelings for or about the subject—was largely playful more often than spiteful. "There’s a give and take between the artist and his subjects," says Zabel. "His intent was to amuse, not offend."

This exhibit gives viewers a rare peek into another aspect of Alexander Calder’s life. Visitors are treated to a journey of his life, from his self-portraits and photographs of his studios, where he worked in "heart-stopping clutter," to his forays into popular culture, the sports world, the art world and back to his personal life.

Get to know Calder again, this time through his portraiture, and see if what his artwork says about others reveals anything else about Calder himself.

"As you read the details, the narrative unfolds," curator Zabel says.

"Calder's Portraits: A New Language," is on display at the National Portrait Gallery through August 14th. Calder's work is juxtaposed with photographs, drawings and caricatures form the Portrait Gallery's extensive collection. View our gallery of Calder's wire portraits below.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Arcynta-Ali-240.jpg)