A Man With a Lot of Heart Valves Donates His Unusual Collection

Minneapolis entrepreneur Manny Villafana says his collection at the American History Museum is filled with stories of both failure and success

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/29/43293e42-c07a-4ee2-b69a-6813aca9e819/heartvalvesdsc5012web.jpg)

In a storage area at the National Museum of American History, Judy Chelnick, a curator of medicine and science, opens a cabinet drawer to reveal some 50 different artificial heart valves. The variations are striking. Some resemble pacifiers, others jewel settings, and yet others look more like the claw crane used to scoop arcade prizes.

“It all has to do with the ebb and flow of the blood that’s passing through, and getting the right pressure,” Chelnick says.

To the uninitiated, the labels affixed to the boxes are unintelligible: “Hufnagel Tri-Leaflet Aortic Valve” and “Cooley-Bloodwell Cutter Prosthetic Mitral Valve.”

But then there are informal titles assigned by Minneapolis collector and philanthropist Manuel “Manny” Villafana, whose company invented the St. Jude valve—the most widely-used mechanical heart valve, who invests in an eponymous Twin Cities steakhouse, and who donated some 70 heart valves to the Smithsonian last January.

Those names have more to do with toilets—plungers, balls and seats. Take an aortic valve designed by Christiaan Barnard, the South African doctor who famously performed the world’s first heart transplant. Villafana’s label reads: “Toilet Ball - Aorta, Toilet Plunger,” and it is dated "1965, University of Cape Town." Indeed the object looks like a toilet ball. Another label states “Toilet Seat, 1967-1968, Schimert-Cutter,” and that too, as advertised, evokes a toilet seat.

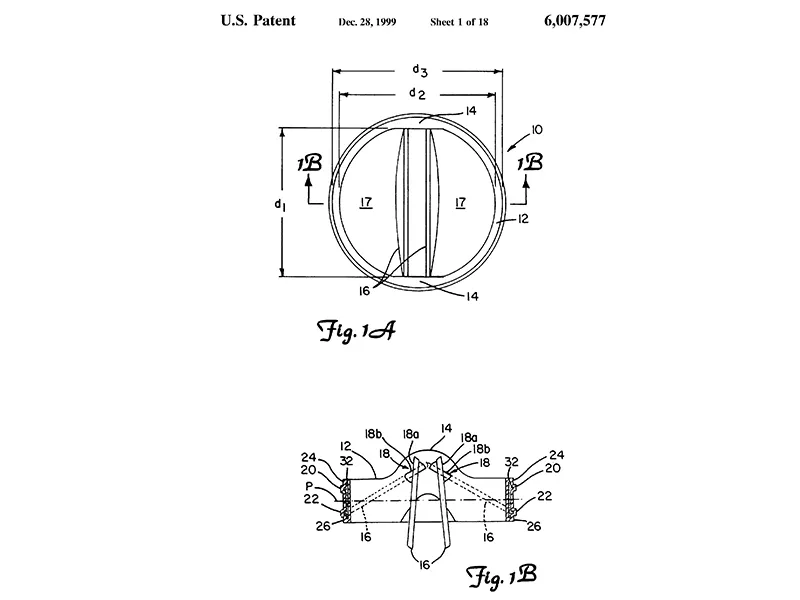

A box housing an object, which most closely resembles an automobile air conditioning vent, states: “This demo valve has been made of anodized aluminum which, by its nature, does not allow us to machine to the necessary tolerances and polish of our all pyrolytic carbon valve. It, in no way, manifests the true quality, finish or operational characteristics of an S.J. [St. Jude] Medical valve, but only grossly demonstrates its concept of function.”

Reached in Minnesota, Villafana says he decided to collect valves—some of them implanted, many not—after realizing heart surgeons had a wide array of valves in their desk drawers, and it was important to protect those objects. (Chelnick specifically wanted to include ineffective devices in the Smithsonian collection: “Not just things that succeeded, but things that didn’t work out as well,” she says.)

Once Villafana had amassed a collection, he wanted it to go to the Smithsonian, where it would be around forever. (Villafana, born in 1940, refers to himself in the third person, and often spoke of his own mortality in a phone conversation.)

“The value of this is that there are always young engineers and students trying to figure it out: ‘Can we make it a better way, and coming up with ideas?’ But those ideas have already been tried. It won’t work,” he says. “I realized if I didn’t do something with them, someone is going to empty out my desk drawer, throw it in the garbage, and poof, they’re gone.”

Doctors, he says, were happy to donate valves to him, especially if they had multiple duplicates. “By that time, everyone knew who I was, as far as heart valves were concerned. Practically everyone was using the St. Jude valve,” he says. “When Manny Villafana walks into an office and says, ‘Hey. Any chance you can share with me some of your old valves?’ He says, ‘Sure.’ Because he knows that when he kicks the bucket that they’re all going into the garbage can.”

Not only are the valves so unique in their designs, but “there’s a story behind every single one of them,” he adds.

The Smithsonian, to Villafana, is an opportunity for legacy. “How often does one have the chance to leave behind something that will be used forever? And that will help in the betterment of technology and to better someone’s life?” he asks.

He takes particular pride in 100 percent of today’s pacemakers, and all of the mechanical heart valves currently in use, operating with technology that he and his companies designed. “I get my jollies out of that,” he adds.

Asked about Villafana and the impact of his work on the industry, Nevan Clancy Hanumara, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology research scientist in mechanical engineering says he has a great deal of respect for "anyone who successfully commercializes a device that improves patient care.”

“The medical device industry is risk averse, hard to fund, expensive, and has an extremely long time scale, hence there are multiple valleys of death for entrepreneurs,” says Hanumara.

Naren Vyavahare, who holds an endowed bioengineering chair at Clemson University in South Carolina, shares that respect.

Prior to the St. Jude valve and its bi-leaflet design, ball-and-cage design valves (like several of the valves Villafana donated to the museum) proved obstructive to blood flow and caused significant clots. “It would either make the valve dysfunctional or cause a stroke related to blood clots travelling to the brain arteries,” Vyavahare says.

The bi-leaflet valves invented by St. Jude Medical “have been best-in-class heart valves, and they still are the major valves used in mechanical valve replacement surgeries,” Vyavahare adds. “They have proven to be durable and have lowest complications rates during long-term implantation. . . . They have literally saved hundreds of thousands of lives over the years.”

Chelnick, the curator, says researchers often come to the museum to study the collection of medical devices. She is also hoping to put together an exhibition one day that will draw upon a “significant part” of the Villafana collection.

The diversity of the objects’ design, she says, appeals to her in particular. A self-declared non-science person, who steered clear of all science (save requirements) in college, Chelnick worked in museums on decorative arts before landing a job at a medical history museum in Cleveland. She found medical history fascinating, and as a decorative arts specialist who understands materials, she appreciates the “art” of the medical devices.

“I love seeing them together in this one drawer,” she says.

Asked to share a compelling anecdote about his collection, Villafana cites the reason he named his company St. Jude Medical. But the story, he says, requires so much time to tell properly, that he asks those inquiring to buy him dinner, “because I want to make sure you’re serious about it,” he says. “It is a valuable story, so it’s going to cost you dinner.”

For those who aren’t in a position to dine with him, he directs readers to YouTube, where a video explains part of his story. But he did offer a short version.

"In the collection, there is the St. Jude heart valve Serial #1, the first one made. It's the most commonly implanted prosthesis in the world with almost 3 million patients. It was named after St. Jude, the patron saint of hopeless cases, because I believe he helped save my son Jude's life."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)