Before SXSW and Ted, A Manic Visionary Revolutionized the American Lecture Circuit

Meet James Redpath, the man who coached national celebrities on how to bring a crowd to its feet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/7f/3d7fa025-464d-483c-ab41-bdbe9688efb1/tctravel023a_front.jpg)

Americans have long loved speechifying. From Barnum to Bono, from Emerson to Clinton, audiences have craved this murky cocktail of sermon and standup. Such speeches peaked in the years after the Civil War, when the wildly popular Redpath Lyceum Bureau delighted audiences nationwide. Forbearer of TED talks and SXSW, Redpath lectures brought out America’s visionaries and thought leaders to entertain, instruct and to make fortunes doing it.

Redpath’s traveling tents, which could seat as many as a thousand, served as America’s “canvas college,” introducing the 19th century’s most prominent reformers, most daring comedians and most scandalous celebrities. In small towns and booming cities massive throngs paid 50 cents to be educated and entertained. The only requirement was that the speakers mesmerize crowds and sell tickets.

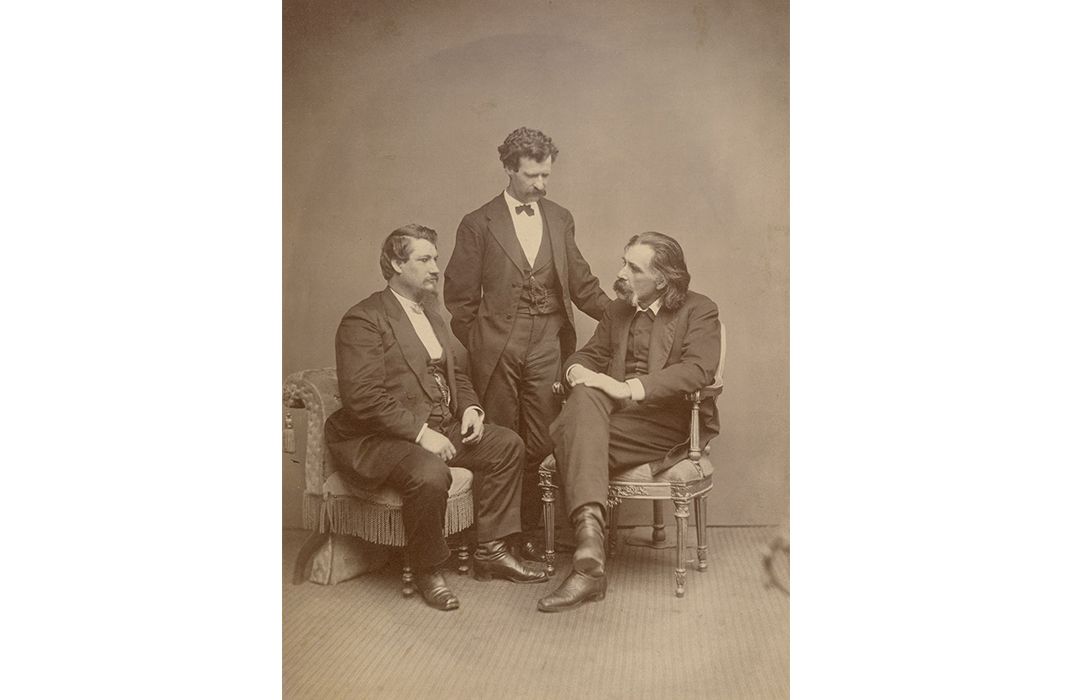

James Redpath was the mad genius behind it all. Mark Twain mocked his bedraggled friend—who stood just 5’4” and weighed 100 pounds—as a “poor, witless, useless weakling.”

But shimmering under the surface was a frenetic innovator, “brainy to the tips of his fingers.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/70/2670f17c-a2b7-48d1-b6db-89b20f16e5db/redpath.jpg)

Born in Scotland, Redpath came to America in the 1840s and over the next half-century, seemed to be everywhere, and know everyone. He lept from one historic hotspot to the next, from fighting slavery with John Brown to ghostwriting Jefferson Davis’ autobiography, befriending prominent writers, activists and inventors in between. But the manic visionary made his name revolutionizing the staid culture of American lecturing.

In the late 1860s Redpath was living in New England, looking for a way to reform society and pay his bills. One day he heard Charles Dickens speak. The English writer, infamous for his arch criticisms of America, complained about life on the road in the massive country. Redpath had a sudden vision. He decided to launch “a general headquarters, a bureau” to send the most thrilling speakers across the nation. Who better to organize it then Redpath, friends with everyone and always looking to make a buck?

He wanted to do more than organize a tour; Redpath dreamed of changing the way people spoke in public. America had a long tradition of sermonizing, with antebellum speakers lecturing at Lyceums that gathered crowds for “instructive” orations during the long winter months when it was too cold to farm. But their “instructive” orations were notoriously dry. Many simply read their speeches. Audiences paid little attention. Even in Congress, politicians drank and gossiped while their colleagues rambled.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/13/81134839-7db5-4273-9f81-41ddb49bfc34/twain.jpg)

Redpath could not tolerate this “sermony style of discourse.” He wanted speakers who would “write for the ear,” who would engage and entertain, stalk the stage and electrify the audience. Redpath especially hated lecturers who read their texts aloud. He joked that reading to an audience was like “making love to a woman by writing my opinion of her and reading it to her.”

So he began organizing tours by speakers who would not let their earnest politics get in the way of a good show. He recruited Frederick Douglass, sick of retelling the story of his escape from slavery, but still capable of firing up massive multiracial audiences. And he brought out the Temperance activist John Gough, whose sweaty, acrobatic account of his years as an alcoholic somehow made prohibition seem fun.

Soon Redpath had a stable of brilliant performers, ranging from activists to comedians. He promoted Anna Dickinson, the combative young women’s rights advocate. Decorous female lecturers usually read their addresses while sitting, but Dickinson paced the stage, depicting men as “the bungling sex” and shouting down hecklers.

He recruited David Ross Locke—the Stephen Colbert of the Civil War—who used a ridiculous persona to promote “liberal causes by seeming to oppose them.”

Then Redpath found Mark Twain. The young writer hung around with a crew of older humorists who would drink (heavily), gossip and steal each other's jokes. Redpath recognized Twain as the matchless entertainer that he was, and pushed him into speaking tours. But it took all of Redpath's tricks to keep Twain there. Twain hated lecturing and subjected his agent to pranks, toying with Redpath's ravenous instinct to promote and publicize. The writer would promise some new event, like walking across the state, then quit after Redpath advertised it in all the papers. Still, Redpath knew how to keep Twain speaking, roping him in with generous advances even as Twain vowed, again and again, “DEAR RED, – I am not going to lecture any more forever.”

Redpath dispatched his speakers across the country, bouncing along in unheated freight cars, giving six lectures a week, eight months a year.

They made tens of thousands of dollars in the process. A diverse crowd of stars began to hang around his Boston headquarters, trading tales in the smoke-filled lounge. More and more speakers joined up, from Native American activists to Gilbert and Sullivan to prominent Mormon divorcées. Redpath briefly roped P.T. Barnum into speaking, but the two flamboyant impresarios quickly fell out over a five-dollar hotel bill.

By the mid-1870s Redpath lost his way, selling his lecture business in 1875 and meandering through sex scandals and strange schemes. Ultimately, he just could not resist exciting new projects. He crusaded for Haiti, then Ireland, then publicized Thomas Edison’s wondrous inventions. He had a few affairs, a handful of breakdowns, and was finally killed when he was run over by a horse-drawn trolley. The lecture series lasted for decades, some still bearing his name, but the movement peaked in the early 1870s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/e0/fae02a7a-41c4-4141-8f33-71e668b55b5a/redpath2.jpg)

How do Redpath’s lectures differ from the revived culture of speechifying, emanating from SXSW, TED talks, and so many bright and pithy speeches posted on Facebook? Redpath’s genius was to challenge the humorless reforming culture of his day. He would bring Chinese Confucians to try to convert deeply Christian crowds and encourage shocking comedians to offend his customers. In the process he remade American popular culture, blending high education and low comedy, forcing the “common men” to think and the cultivated to laugh.

Today's talkers could use some of Redpath’s verve. It is wonderful to see millions sharing educational lectures online, but the new speechifying class exudes some of the smug holiness that Redpath set out to destroy. We've lost the playfulness of a Redpath lecture; replaced with constant claims that this very traditional style of public speaking is somehow “disruptive.” While Redpath pushed Victorians to enjoy themselves, “sermony” TED Talks lead with a dreadful earnestness, each purporting to fix the world.

The key to Redpath’s vision was that he never gave his audience a pat on the back. Today’s speakers might move in the same direction, challenging our uncontested faith in technology, or the desire to solve big social problems with “one weird trick,” explained in 18 minutes. Having revived America’s long tradition of sermonizing, maybe we’re could use a few lessons from Redpath.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JonGrinspan008V2_web_thumbnailcrop.png)