Just Another #ManicureMonday for Women Scientists and Their Dirty Nails

For a Smithsonian researcher, Monday is a day to honor the women in science and other uses for nail polish

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/c5/8ec5c4e0-e764-48fe-8809-62825e4c2abd/nailweb.jpg)

Two years ago Hope Jahren, an isotope geochemist and laboratory scientist, studying photosynthesis at the University of Hawaii Manoa, hijacked Seventeen Magazine’s #ManicureMonday, which prompts women to post pictures of their freshly manicured hands. She tweeted:

Purpose of #ManicureMonday is to contrast real #Science hands against what @seventeenmag says our hands should look like. All nails welcome.

— Hope Jahren (@HopeJahren) November 17, 2013And then tweeted this picture of her well-groomed, but unmanicured, holding a glass vial, and labeling it: #Science:

When subsequent tweets asked “Why?” Jahren followed with:

Take pic of your hand doing something #Science & post to #ManicureMonday (on Monday) Polish optional. RT @kejames How do we participate?

— Hope Jahren (@HopeJahren) November 15, 2013Thus began an emotionally charged verbal tennis match about women in science, stereotypes, shaming, STEM and gender roles on Twitter and Reddit, as well as commentary featured in blogs like Slate Magazine, Scientific American and The Huffington Post.

While the #ManicureMonday #Science hijack seemed to begin with good intentions, it ultimately sparked controversy. But controversy is good—it makes us stop and think about our worldviews. It encouraged individuals to examine things like motivation, assumptions and perceptions of all kinds, including dichotomous thinking like “you can either be smart or manicured.”

There are plenty of scientists who enjoy adorning their finger and toe with nail polish, but for many of us there is a practical reason we forego gilding. That is, doing some kinds of science simply destroys manicures and pedicures. Whether it’s from wearing synthetic rubber Nitrile gloves, from donning dive booties, or deploying research gear like nets and samplers, or scrambling around research boats, or tromping through forests, or wading through estuaries, streams and marshes, or performing experiments in wet labs or outdoor mesocosms, manicured fingers and toes take a beating. Yet, we still use nail polish. We just use it in a different way.

Since the 1940s, nail polish has been an invaluable tool in a scientists’ toolbox. It’s cost-effective, can be found just about anywhere and comes in a full range of colors, which makes it useful in marking organisms in research studies. Scientists have used nail polish to mark snails, lobsters, crabs, lizards, tortoises, insects and birds in studies investigating growth, mortality, movement and distribution, habitat preference, sexual selection, nestling behavior, predator-prey interactions and foraging behavior.

At the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, we’ve used nail polish in a couple of different ways:

- The Marine and Estuarine Ecology Lab used colored nail polish (right) to mark oysters for shallow-water hypoxia field studies investigating Dermo disease in the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Two days before field deployment, scientists used blue and purple nail polish to distinguish between initially infected oysters and initially uninfected oysters. They also tagged oysters with a number code to track individual oyster growth and mortality. Results from this study recently appeared in the online journal PlOS ONE.

- The Marine Invasions Lab used red nail polish during an invasive European Green Crab (Carcinus maenas) eradication study in a lagoon near Stinson Beach, California. European Green Crabs are adaptable, voracious predators that can consume 40 half-inch clams per day and other crabs of similar size. The main focus of this study was to test if eradication was feasible, and to track its long-term effects on native crabs. To do this, researchers and volunteers set several crab traps in the lagoon. While removing the invasive European Green Crabs, they identified all native crabs to species, measured them and numbered adults with a “quick-dry, long-lasting and chip resistant” nail polish before returning them to the lagoon. Since each crab had a unique nail polish number, researchers could easily track the movements of individuals over the course of the eradication study.

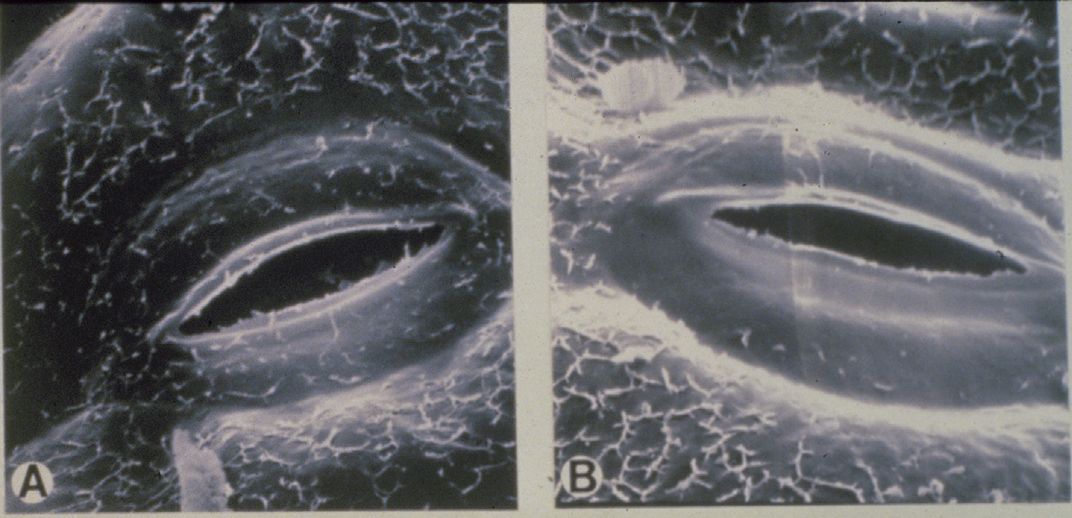

- SERC’s former Carbon Dioxide and Plant Physiology lab, a.k.a. the CO2 Lab, had quite possibly the most creative nail polish use: creating leaf casts. First, they painted clear nail polish on the surface of leaves. Once it dried, they peeled the clear nail polish away from the leaf, which left a kind of cast or impression of the leaf surface in the dried nail polish. When they looked at the impressions under a microscope, they counted the tiny mouth-shaped bumps, or stomata, to estimate stomatal density. Why estimate stomatal density? When atmospheric carbon dioxide increases, stomatal density often decreases. This decrease may affect local plant communities and, by extension, global ecosystems. Understanding the effects of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide on plants and plant communities is an ongoing focus of SERC research.

To Polish or Not To Polish

So, feel free to adorn your finger and toe with nail polish, or don’t and save it for your research toolbox—but why not both? Do you have pictures of your own hands doing science in a classroom, while volunteering or working on a citizen science project? Maybe you have pictures of a research study using nail polish as a tool? Why not post them on Twitter to @SmithsonianEnv, using the hashtags #ManicureMonday #Science? As always, all nails are welcome.

This article was originally published on the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center's blog "Shorelines."