Is It Time for a Reassessment of Malcolm X?

A Smithsonian Channel film, “The Lost Tapes,” challenges misconceptions about the charismatic leader

![a4000028b[1].jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/HxoY2apqGHl9Z0JPdKvGkeFuefw=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale()/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/d2/91d24529-2501-4614-81e8-19d28dfa39a1/a4000028b1.jpg)

The voice of Malcolm X is like a baritone saxophone—powerful, full, and deep with a gravely gravitas that demands your attention. What better instrument for a man whose forceful, fiery speeches transfixed the nation in the midst of the 1960s civil rights movement—and made tangible the anger and frustration of African-Americans who were simply catching hell.

“We’re not brutalized because we’re Baptists. We’re not brutalized because we’re Methodists. We’re not brutalized because we’re Muslims. We’re not brutalized because we’re Catholics,” Malcolm X tells a rapt audience. “We’re brutalized because we are black people in America.”

That is the opening quote in the Smithsonian Channel documentary “The Lost Tapes: Malcolm X.” The one-hour film takes viewers on a journey through some of the pivotal years of an activist some thought of as a militant who preached hate against white people at a time when blacks across the nation were being economically, emotionally and physically oppressed. But Malcolm X’s views evolved after taking the traditional Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca known as the Hajj in 1964, after which he changed his name to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. This film tells his story through interviews and speeches, and includes some footage from Nation of Islam rallies that has never been seen before. There is no narrator—and that pleases his third daughter, Ilyasah Al Shabazz.

“We finally have the opportunity to hear directly from our father’s mouth,” Shabazz said at a recent screening of “The Lost Tapes” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she told the audience how she began to learn in college about the inaccurate portrayals of her father’s character and work. “I was overwhelmed with emotion when I first saw it and I thought that it was a great piece of work.”

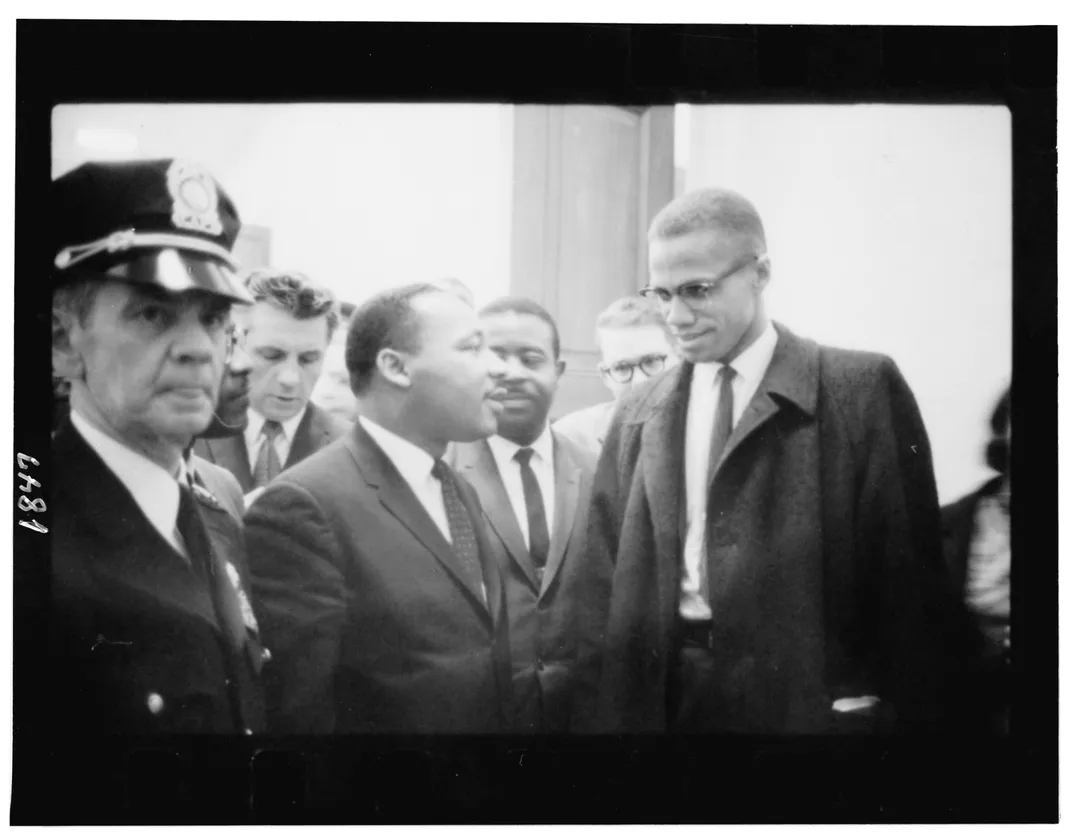

The first half of the film takes viewers through some of the best known moments in Malcolm X’s life—from his time as a minister and spokesman for the Nation of Islam and its leader Elijah Muhammad to his intellectual battles with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr over their opposing views on how best to obtain civil rights for African-Americans. King favored non-violent protests while Malcolm X lobbied for separation of blacks from white society. But the second half looks at a Malcolm X whose views change after his Hajj, and Shabazz says many people aren’t familiar with that side of her father. She’s been thinking about whether there’s enough context in the film for the things he does and says—and the familiar image of Malcolm X carrying a rifle and explaining why he does so.

“When we show Malcolm we usually just show his reaction—without ‘O.K. I have a rifle. Someone bombs my house. I have a rifle.’ Everybody laughs at that instead of the fact that his house was firebombed. The fire bomb was thrown into the nursery where his children slept, where his pregnant wife lived, while he was looking for solutions to the human condition,” Shabazz explains. “They don’t take into consideration that he was a young man when he committed himself . . . threw himself into the civil rights movement and it was Malcolm who introduced a human rights agenda to the civil rights movement. . . . He was a compassionate man. He was caring, loving, kind. All of the words that we don’t use when we describe Malcolm, instead of realizing here you have a young man who had a profound reaction because of his compassion.”

Malcolm X grew up in extreme poverty, and spent years as a hustler and pimp on the streets of Roxbury and Harlem before ending up in Norfolk State Prison in Massachusetts where he converted to Islam in 1947. He met the Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad in 1952, and began organizing Muslim Temples from New York to the South and the West Coast. He founded the Nation’s newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, and rapidly rose through the ranks to eventually become the Nation’s national representative. But tensions arose between Malcolm X and Muhammad, which erupted after he violated orders to stay quiet after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

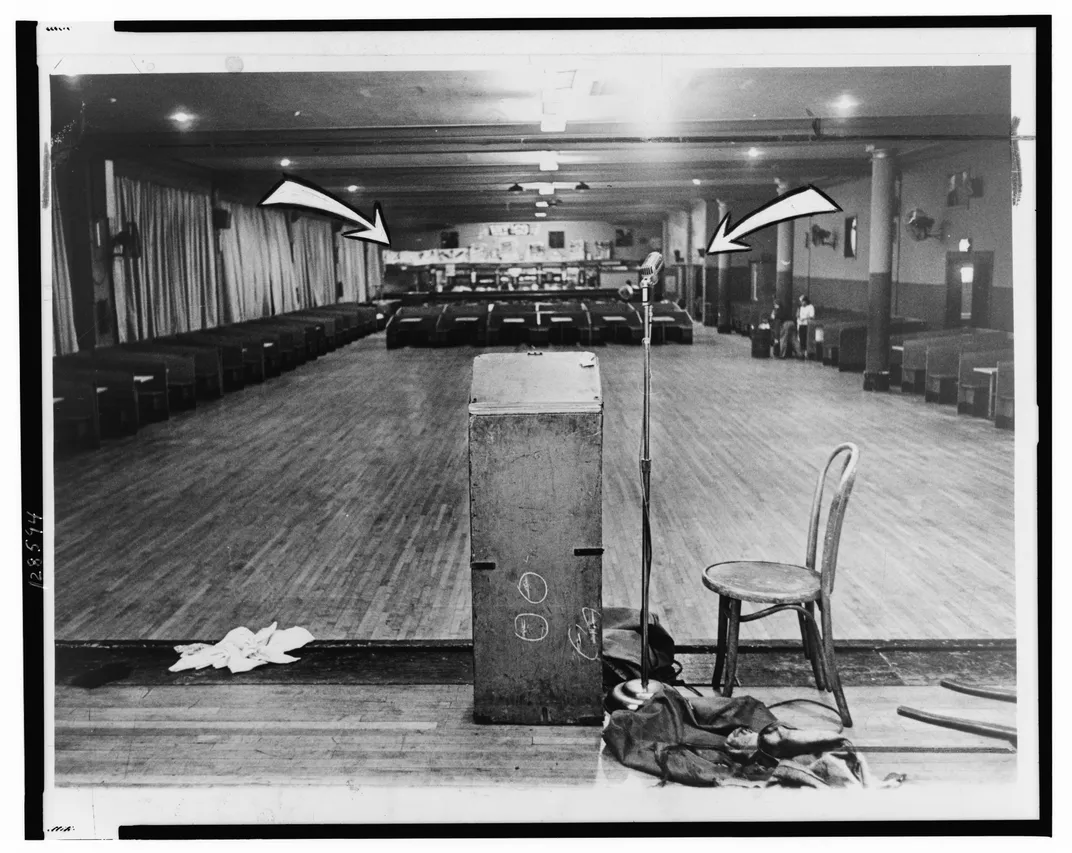

Malcolm X left the Nation the next year, and revealed sexual misconduct by its former leader. He formed his own organizations, the Muslim Mosque Inc. and the Organization for Afro-American Unity. On June 28, 1964, Malcolm X spoke at the founding rally for the latter group, urging blacks to defend themselves “by any means necessary.” He was assassinated on February 21, 1965 by three gunmen who rushed the stage at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem where he was preparing to give a speech. The documentary includes rarely heard recordings of the aftermath of the shooting.

“The Lost Tapes” has been screened in several cities across the nation including New York and Washington D.C., and those behind the movie think it is important for it to be seen right now, in the midst of the racial turmoil that continues to divide the nation.

“People tend to stereotype Malcolm X and he’s seen as just a radical rabble rouser. And when you watch him in this film, which really lets him speak for himself, you see a much more nuanced, a much more thoughtful, a much more charismatic and just highly intelligent man,” says David Royle, executive vice president for production and programming at the Smithsonian Channel. “You see how his thoughts are evolving and my biggest takeaway was the great sense of loss at the end. This was a person who was on a journey and you may criticize various stages of that journey but where he was heading was really interesting and very important.”

The film’s producer, Tom Jennings, who also did the Peabody Award-winning “MLK: The Assassination Tapes,” says it was a tremendous honor to tell this story that could have been 12 times longer about this amazing speaker and human being. He says it was also a challenge, partly because of the time constraints and partly because he was telling the story of an iconic leader for a general audience that might not know much about him.

“This is for people that don’t necessarily know much about Malcolm X, perhaps just his name,” Jennings explains. “This is not a feature film. This will go on television. You know we’re all poised to change the channel and so we had to take his words and make them entertaining—not in a “Star Wars” sense but we had to make them so . . . people will stop and listen. . . . I like making these kinds of films using historical archive because it almost holds a mirror up to ourselves and it allows us to look at who we are, whether it’s this event or Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, where we’ve been and have we changed or have we not changed at all.”

Jennings says there is a lot of historical Malcolm X-related film footage out there; including Nation of Islam color footage from some of their rallies that had not been seen before. Some of that came from Washington University in St. Louis, and there was even film belonging to Elijah Muhammad’s dentist, but the producers weren’t able to get permission to use some of it because they couldn’t verify the owners. There were also things he learned that surprised him in “The Lost Tapes,” such as the fact that Muhammad Ali had to break his friendship with Malcolm X to receive his personal Muslim name from Elijah Muhammad.

“It was a complicated relationship,” explained Damion Thomas, a curator at the African American Museum at the Institution’s screening of the film. “When Malcolm X leaves the Nation he tries to get Muhammad Ali to come with him and it becomes a battle between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad for the allegiance of Muhammad Ali who at the time is the most well-known athlete in the world. What’s interesting is one of the reasons why Muhammad Ali decides to stay with Elijah Muhammad is that he felt like Malcolm X was trying to politicize this.”

“I thought that was a disservice to my father . . . to say that he politicized his friendship with Muhammad Ali,” Ilyasah Al Shabazz says forcefully, adding that Ali later said he regretted having turned his back on Malcolm X.

Curator Thomas says it is important that this film was made at this time because there are many misconceptions about Malcolm X and there are many ways that he has been interpreted. He adds that it is important to have competing notions about the charismatic leader because then people have an opportunity to think through complex issues.

“The reason people really have to understand Malcolm X, whether you agree with him or not, he was committed to the upliftment of black people, and I think that’s the most important thing that we should know about Malcolm X,” Thomas says.

“The Lost Tapes: Malcolm X,” premieres on the Smithsonian Channel on February 26 at 8 p.m. Eastern Standard Time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)