The Incomparable Legacy of Lead Belly

This week a new Smithsonian Folkways compilation and a Smithsonian Channel show highlight the seminal blues man of the century

“If you asked ten people in the street if they knew who Lead Belly was,” Smithsonian archivist Jeff Place says, “eight wouldn’t know.”

Chances are, though, they’d know many of Lead Belly songs that have been picked up by others. Chief among them: “Goodnight Irene,” an American standard made a No. 1 hit by The Weavers in 1950, one year after the death of the blues man who was first to record it, Huddie Ledbetter, better known as Lead Belly.

But the roster also includes “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” the spooky song that capped Nirvana’s Grammy winning No. 1 “Unplugged in New York” album in 1994 that sold 5 million copies.

And in between? “Rock Island Line,” recorded by both Lonnie Donegan and Johnny Cash; “House of the Rising Sun,” made a No. 1 hit by the Animals; “Cotton Fields,” sung by Odetta but also the Beach Boys; “Gallows Pole,” as interpreted by Led Zeppelin and “Midnight Special” recorded by Credence Clearwater Revival and a host of others.

Also on the list is “Black Betty,” known to many as a hard-hitting 1977 rock song by Ram Jam that became a sports arena chant and has been covered by Tom Jones.

Few of its fan would realize the origins of that hit as a prison work song, in which its relentless “bam de lam” is meant to simulate the sound of the ax hitting wood, says Place, who co-produced a five-disc boxed set on Lead Belly’s recordings out this week.

John and Alan Lomax, the father and son team of musicologists who recorded prison songs and found Lead Belly chief among its voices in 1933, wrote that “Black Betty” itself referred to a whip, though other prisoners have said it was slang for their transfer wagon.

Either way, it’s an indication of how much the songs of Lead Belly became ingrained into the culture even if audiences aren’t aware of their origins.

Today, 127 years after his birth, and 66 years after his death, there is an effort to change that.

On Feb. 23, the Smithsonian Channel will debut a documentary about the twice-jailed singer who became so influential to music, “Legend of Lead Belly,” including striking color footage of him singing in a cotton field and lauditory comments from Roger McGuinn, Robby Krieger, Judy Collins and Van Morrison, who just says “he’s a genius.”

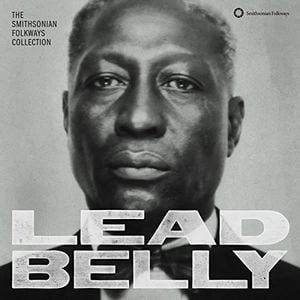

Then on Feb. 24, Folkways releases a five-disc boxed set in a 140-page large format book that is the first full career retrospective for the blues and folk giant. On April 25, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts will put on an all-star concert that echoes the original intention of the project, “Lead Belly at 125: A Tribute to an American Songster.”

The 125 milestone is meant to mark the anniversary of his birth to sharecroppers in rural Louisiana. But even if you believe some research that says he was born in 1889, that marker has still passed. “Had things happened quicker,” Place says, it all would have been completed for the 125th, who previously put together the massive “Woody at 100” collection on Woody Guthrie in 2012. The vagaries of collecting materials and photographic rights for the extensive book, and shooting the documentary took time.

It was a little easier to assemble the music itself since the Smithsonian through its acquisition of Folkways label, has access to the full span of his recording career, from the first recordings in 1934 to the more sophisticated “Last Sessions” in 1948 in which he was using reel-to-reel tape for the first time, allowing him to also capture the long spoken introductions to many of the songs that are in some cases as important historically as the songs themselves.

Lead Belly wrote dozens of songs, but a lot of the material that he first recorded were acquired from hearing them first sung in the fields or in prison, where he served two stints. He got out each time, according to legend, by writing songs for the governors of those states, who, charmed, gave him his freedom.

The real truth, Place’s research shows, is that he was up for parole for good behavior around those times anyway.

But a good story is a good story. And when the Lomaxes found in Lead Belly a stirring voice but a repository for songs going back to the Civil War, the incarcerations were such a big part of the story, it was often played up in the advertising. Sometimes, he was asked to sing in prison stripes to drive home the point.

And newspapers couldn’t resist the angle, “Sweet Singer of the Swamplands here to Do a Few Tunes Between Homicides” a New York Herald Tribune subhead in 1933 said. “It made a great marketing ploy, until it got too much,” Place says.

Notes from the singer’s niece in the boxed set make it clear “he did not have an ugly temper.” And Lead Belly, annoyed that the Lomaxes inserted themselves as co-writers for purposes of song publishing royalties. “He was at a point of: enough is enough,” Place says.

While the blues man was known to make up songs on the spot, or write a sharp commentary on topical news, he also had a deep memory of any songs he had heard, and carried them forward.

“Supposedly Lead Belly first heard ‘Goodnight Irene,’ sung by an uncle in around 1900,” Place says. “But it has roots in this show tune of the late 19th century called ‘Irene Goodnight.’ He changed it dramatically, his version. But a lot of these songs go back many, many years.”

While the young Lead Belly picked up his trade working for years with Blind Lemon Jefferson, his interests transcended the blues into children’s songs, work songs, show tunes and cowboy songs.

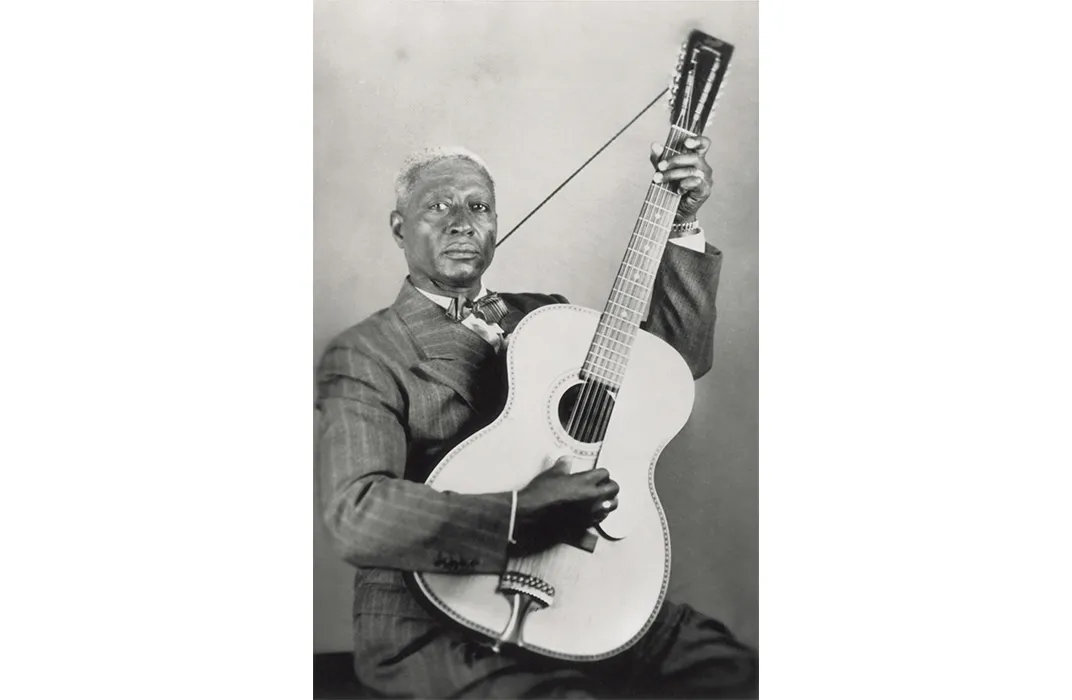

And he stood out, too, for his choice of instrument—a 12-string guitar, so chosen, Place says, so it could be heard above raucous barrooms where he often played. “It worked for him, because he played it in a very percussive way, he was a lot of times trying to simulate the barrelhouse piano sound on the guitar.”

He played a variety of instruments, though, and can be heard on the new collection playing piano on a song called “Big Fat Woman,” and accordion on “John Henry.” While a lot of the music on the new set was issued, a couple of things are previously unreleased, including several sessions he recorded at WNYC in New York, sitting in the studio, running through songs and explaining them before he came to his inevitable theme song, “Good Night Irene.”

One unusual track previously unreleased from the “Last Session” has him listening and singing along to Bessie Smith’s 1929 recording of “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.”

“Now that’s really cool,” Place says. “I’d play it for people who came through, musicians, and they’d say, ‘That blew my mind, man.’”

The legacy of Lead Belly is clear in the film, when John Reynolds, a friend and author, quotes George Harrison as saying, “if there was no Lead Belly, there would have been no Lonnie Donegan; no Lonnie Donegan, no Beatles. Therefore no Lead Belly, no Beatles.”

And even as Place has been showing the documentary clips in person and online he’s getting the kind of reaction he had hoped. “People are saying, ‘I knew this music. I didn’t know this guy.”

Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/2d/542d9972-bfd6-4c12-966f-fd8c5f8f431b/sfw40201_leadbellysfcollectioweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/c6/5ec610c3-5bbe-4a6b-a15f-f9b2726c6478/sfw40201web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)