If Only Hollywood Would Show Us Lincoln’s Second Inaugural

Our pop culture curator Amy Henderson strolls the halls of the Old Patent Building imagining the scene of Lincoln’s 1865 inaugural ball

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/99/7299279a-5fd4-4eab-9917-d4151262a814/screen_shot_2021-01-08_at_40725_pm.png)

Editor’s Note, January 8, 2021: This article was written in 2013; in 2021, there will not be inaugural balls held in the Convention Center due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Inaugural fever is sweeping Washington, D.C. The “Official Inauguration Store” is now open down the block from the National Portrait Gallery, parade viewing stands have been constructed along Pennsylvania Avenue, and street vendors are hawking T-shirts and buttons that bark out the coming spectacle. The Inauguration Committee expects 40,000 people at the two official inaugural balls that will be held in city’s cavernous Convention Center.

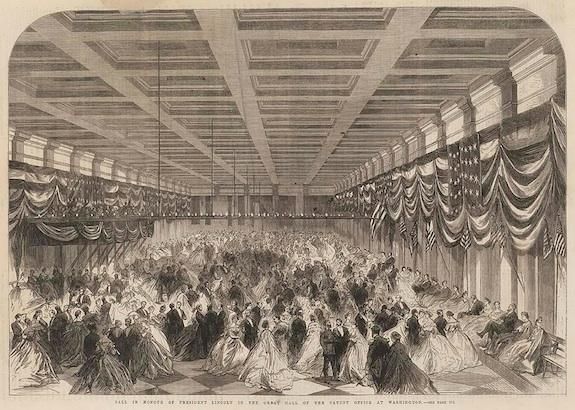

At the Portrait Gallery, I decided to soak up some of this festive spirit by imagining the inaugural ball held for Abraham Lincoln on the building’s top floor in 1865. The museum was originally built as the U.S. Patent Office, and its north wing was a vast space deemed perfect to house the grand celebration for Lincoln’s second inauguration.

Earlier, the space had served a very different purpose as a hospital for Civil War soldiers wounded at Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Poet Walt Whitman, who worked as a clerk at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Patent Office Building, had been an orderly who treated these soldiers. The night of the inaugural ball, he wrote in his diary, “I have been up to look at the dance and supper rooms. . . and I could not help thinking, what a different scene they presented to my view since fill’d with a crowded mass of the worst wounded of the war. . .” Now, for the ball, he recorded that the building was filling up with “beautiful women, perfumes, the violins’ sweetness, the polka and the waltz.”

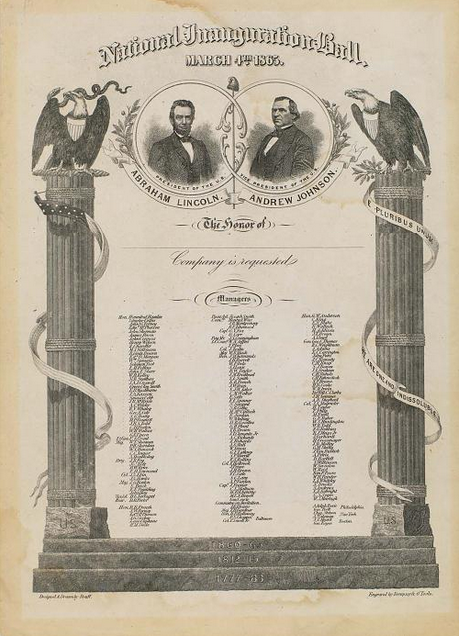

Engraved invitations were given to dignitaries while public tickets, admitting a gentleman and two ladies, were sold for $10. The day of the ball, according to Margaret Leech’s evocative Reveille in Washington, 1860-1865, the building bustled with preparations for the big event: a ticket office was set up in the rotunda, and the ballroom band rehearsed while gas jets were strung from the ceiling in the north wing to provide lighting. Workers were draping the walls with American flags and a raised dais was built for the presidential party and furnished with blue and gold sofas.

As I walked the path inaugural guests took to the ballroom, I appreciated the special challenge facing women in hoop-skirted gowns as they negotiated the grand staircase. At the top, people would have entered the ornate Model Hall, with its stained glass dome and gilded friezes, and then promenaded down the south hall past cabinets filled with patent models. Early in the evening, guests were serenaded by military music from Lillie’s Finley Hospital Band; after ten, the ballroom band signaled the official beginning of the festivities by playing a quadrille.

Just before 11 p.m., the military band struck up “Hail to the Chief” and the President and Mrs. Lincoln entered the hall and took their seats on the dais. Lincoln was dressed in a plain black suit and white kid gloves, but Mrs. Lincoln sparkled in a dress of rich white silk with a lace shawl, a headdress of white Jessamine and purple violets, and a fan trimmed in ermine and silver spangles.

Standing in what is today called the “Lincoln Gallery,” I found the vision of the 1865 spectacle elusive and hazy. Victorian culture had strict rules for everything, and the etiquette governing waltzes, schottisches, reels, and polkas was as carefully codified as knowing the proper fork to use at a formal dinner. It seemed a tough way to have a good time.

And what did the ball actually look like? Engravings of the event exist, but there are no photographs–and how could static images convey this spectacle’s electric sense of excitement? Moving images weren’t invented by the 1860s, but even later, movie re-creations of Civil War-era balls fared little better. Both Jezebel (1938) and Gone with the Wind (1939) use ball scenes to capture the idea of fundamental codes being flaunted: in Jezebel, Bette Davis’s character stuns the ballroom by appearing in a brazen red dress rather than the white expected of someone of her unmarried status; in GWTW, Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett—a recent war widow—shocks the guests by dancing a Virginian Reel with Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler. In each case, a highly-synchronized choreography shows people dancing beautifully across the ballroom floor. But the Hollywood vision is about as emotionally charged as porcelain figures gliding around the surface of a music box.

It wasn’t until I saw the new film Anna Karenina that I felt the dynamism that must have fueled a Victorian ball. Tolstoy published the novel in serial form between 1873 and 1877, setting it in the aristocratic world of Imperial Russia. The 2012 film directed by Joe Wright is a richly stylized, highly theatrical version envisioned as “a ballet with words.” Washington Post dance critic Sarah Kaufman has evocatively described the ball scene where Anna and Vronsky first dance, noting how their “elbows and forearms dip and entwine like the necks of courting swans.” For Kaufman, the movie’s choreography created a world “of piercing, intensified feeling.”

The Lincoln inaugural ball may have lacked a dramatic personal encounter such as Anna and Vronsky’s, but the occasion was used by Lincoln to express the idea of reconciliation. While he walked to the dais with House Speaker Schuyler Colfax, Mrs. Lincoln was escorted by Senator Charles Sumner, who had fought the president’s reconstruction plan and was considered persona non grata at the White House. In a clear display of what is today called “optics,” Lincoln wanted to show publicly that there was no breach between the two of them, and had sent Sumner a personal note of invitation to the ball.

The 4,000 ball-goers then settled in for a long and happy evening of merry-making. As Charles Robertson describes in Temple of Invention, the Lincolns greeted friends and supporters until midnight, when they went to the supper room and headed a large banquet table filled with oyster and terrapin stews, beef a l’anglais, veal Malakoff, turkeys, pheasants, quail, venison, ducks, ham, and lobsters, and ornamental pyramids of desserts, cakes, and ice cream. Although the president and his wife left about 1:30 a.m., other revelers stayed on and danced until dawn.

After nearly five years of a terrible war, Lincoln hoped that his inaugural ball would mark a new beginning. He also understood that for nations as well as for individuals, there were times to pause and celebrate the moment.

As I wrapped up my recreated vision of the ball and left the Lincoln Gallery, I smiled and whispered, “Cheers!”

A regular contributor to Around the Mall, Amy Henderson covers the best of pop culture from her view at the National Portrait Gallery. She recently wrote about Downton Abbey and dreams of a White Christmas, as well as Kathleen Turner and the Diana Vreeland.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)