How TV’s “Person of Interest” Helps Us Understand the Surveillance Society

The creative minds behind the show and The Dark Knight talk about Americans’ perception of privacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/poi-631.jpg)

“You are being watched.” This warning opens every episode of the hit CBS TV series, “Person of Interest,” created by The Dark Knight screenwriter Jonathan Nolan. In the wake of recent revelations about NSA surveillance, however, those words hew closer to reality than science fiction.

The “Machine” at the center of “Person of Interest” is an all-seeing artificial intelligence that tracks the movements and communications of every person in America—not through theoretical gadgetry, but through the cell phone networks, GPS satellites and surveillance cameras we interact with every day. The show’s two main characters, ex-CIA agent John Reese (Jim Caviezel) and computer genius Harold Finch (Michael Emerson), use this power for good, chasing the social security numbers the system identifies to prevent violent crimes, but they’re constantly fighting to keep the Machine out of the wrong hands.

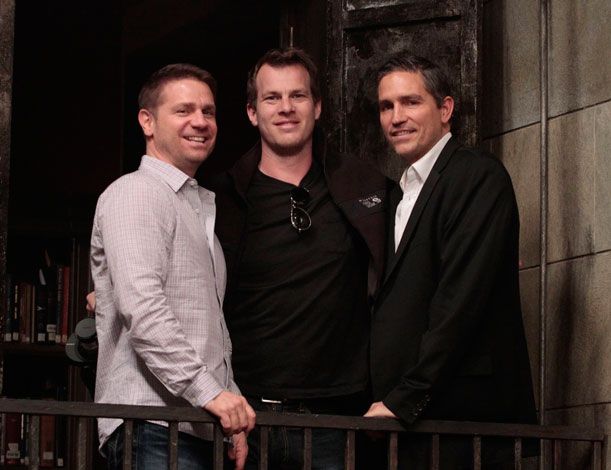

“Person of Interest” has been ahead of the curve on government surveillance since it debuted in 2011, but showrunners Nolan and Greg Plageman (NYPD Blue, Cold Case) have been following the topic for years. Both writers will appear at the Lemelson Center symposium, “Inventing the Surveillance Society,” this Friday, October 25, at 8 p.m. We caught up with the pair to talk about the balance between privacy and security, the “black box” of Gmail and the cell phone panopticon in Nolan’s The Dark Knight.

I want to start with the elephant in the room: the NSA spying revelations. Now that we have definitive proof that the government is watching us, you guys get to say, “I told you so,” with regard to the surveillance on “Person of Interest.” How did you react when you heard about the government’s PRISM surveillance program, leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden?

Jonathan Nolan: With a mixture of jubilation and horror. “We were right, oh, dear, we were right.” Shane Harris , who’s joining us on the panel on Friday, is the one we went to again and again for research, and PRISM was really the tip of the iceberg. Not to sound snobby, but for people who were carefully reading the newspapers, they weren’t revelations at all. William Binney, another NSA whistleblower who’s not on the run, has been saying this publicly for years, which points to this other interesting aspect—the fact that the general public may not care if there’s a massive surveillance state. As the story’s developed, there’s been a slow trickle of information from Glenn Greenwald and the Guardian and the Washington Post, in terms of the documents they have from Snowden, to try to keep the story on the front burner. Clearly the story has got traction. But to what degree the public will actually put up with it is actually a question we’re trying to deal with now on the show.

Were you surprised by the public’s response, or lack thereof?

Greg Plageman: Yeah, I really think the capacity for outrage has been mollified by convenience. People love their phones, they love their Wi-Fi, they love being connected, and everything that’s wired is now being pushed into the cloud. We use it all the time, every day, and we can’t imagine our lives now without it. What the president has been saying, how we have to strike a balance between privacy and security—the problem is they don’t. They never do. And they wouldn’t have bothered even paying lip service to it if Snowden hadn’t blown the whistle. So I think now people are reeling from the “OK, so what?” When you tell them the consequence is we’ll be less secure, or you lose some convenience in your life, that’s when people tend to become placated. I think that’s a scary zone where we come in as entertainers and say, let’s present to you the hypothetical, dramatically, of why you should care. That’s the fun of our show.

How do you personally weigh in on that debate? How much liberty do you feel we can or should sacrifice for security?

Nolan: There’s a reason why people send letters with wax seals. That sense of privacy, the conflict between the state and the needs of the citizens, has been around for an awfully long time. We’re quite distrustful, at least in the writers’ room, of anyone who comes in with an over-simplistic answer to that question. It’s all terrible or, in the name of security, you can have access to all of my stuff, is an answer that is only acceptable, if possible, in the immediate short term, where we’re not at war, and there’s no widespread suspicion of the American public.

We’ve said this from the beginning, from the pilot onwards: privacy is different from what have you got in the bag. When the government takes your privacy, you don’t necessarily know that it’s been taken from you. It’s a fungible, invisible thing. That’s why this argument that has been hauled out into public view by Snowden is a very healthy one for the country to be having. If someone takes away your right to express yourself or your right to assemble or any of the rights in the Bill of Rights, you’re going to know about it. But when someone takes away your privacy, you may not have any idea until it’s far too late to do anything about it.

How did you develop the Machine in “Person of Interest”? Why did you make it work the way it does?

Nolan: We just use our imagination. We did research. Aspects of the show that at first blush, when the pilot first came out, people kind of dismissed as curios—like, why don’t they find out if the person is a victim or a perpetrator, why don’t they get any more information than a social security number? It’s a great jumping-off point for a nice piece of drama, absolutely. We’re not shy about that. But actually, a lot of the mechanism of the Machine was based on Admiral Poindexter and Total Information Awareness, which was the great-granddaddy of PRISM.

Poindexter is a really interesting Promethean figure who figured out a lot of what the general public is now just starting to get wind of. The tools were already here to peel back all of the layers of every person in the United States. It’s now become increasingly clear that there is no way to be sure that you’ve hidden your voice or email communications from the government. It’s almost impossible. If you want to communicate privately, it’s a person-to-person conversation and your cell phone is literally left elsewhere or broken, like we do in our show all the time, or handwritten messages. We really have stepped into that moment.

So the question was how do you go about this conscientiously? If we were to build this, how do you ensure that it can’t be used for corrupt purposes? How can you be sure that it isn’t used to eliminate political rivals or to categorize Americans according to their political profiles or their leanings, all that sort of stuff? It seemed like the simplest answer to that question was to make this thing a black box, something that absorbs all this information and spits out the right answers, which interestingly is exactly how Gmail works. That’s why we’re all willing to use Gmail—because we are promised that a human will never read our emails. A machine will read them; it will feed us ads, without invading our privacy. And that is a compromise we’ve been willing to make.

The show explicitly states that the Machine was developed in response to 9/11, that 9/11 ushered in this new era of surveillance. Right now, it seems we might be entering a new post-Snowden era, in which we, the general public, are aware that we’re being watched. How will the show respond to that new reality—our reality, outside the world of the show?

Plageman: In terms of whether or not we’re entering another era, it’s difficult to say when you realize that the assault on privacy is both public and private now. It’s Google, it’s Facebook, it’s what you voluntarily have surrendered. What Jonah and I and the writers have been talking about is: What have you personally done about it? Have you changed your surfing habits? Have you gone to a more anonymous email provider? Have any of us done any of these things? There’s a bit of a scare, and we all react and say, wait a minute, do I need to be more privacy-conscious in terms of how I operate technology? And the truth is it’s a huge pain in the ass. I’ve tried a couple of these web-surfing softwares, but it slows things down. Eventually, if you want to be a person that’s connected, if you want to stay connected to your colleagues and your family, you realize that you have to surrender a certain amount of privacy.

I also believe, just having a son who’s now entering his teens, that there’s a huge generation gap between how we view privacy. I think older generations see that as something that we’re entitled to, and I think, to a certain degree, younger generations who’ve grown up with Facebook see it as something that’s already dead or wonder if it really matters, because they don’t understand the consequences of the death of privacy.

Nolan: In terms of the narrative of our show, we’ve already started looking into the idea that there will be a backlash. Maybe this is wishful because we’ve looked at this issue for so long the slightly underwhelming response to the revelations by Snowden. We’re certainly not looking for people to take revolution in the streets. But you feel like it would be some consolation if there was an aggressive debate about this in Congress—and quite the opposite. You had both political parties in lockstep behind this president, who didn’t initiate these policies but has benefited from the extended power of the executive, in place for generations of presidents from the postwar environment, from Hoover and the FBI onwards. There isn’t much debate on these issues, and that’s very, very frightening. We’re very close to the moment of the genie coming completely out of the bottle.

One of the questions that Shane deals with most explicitly in his book is storage. It sounds like a banality, like the least sexy aspect of this, but storage in many ways may actually be the most profound part of this. How long is the government able to hang on to this information? Maybe we trust President Obama and all the people currently in power with this information. Who knows what we’ll think of the president three presidents from now? And if he still has access to my emails from 2013, in a different political environment in which suddenly police that are mainstream now become police, or people are sorted into camps or rounded up? It sounds like tinfoil hat-wearing paranoia, but in truth, if we’re looking at history realistically, bad things happen, fairly regularly. The idea that your words, your associations, your life, to that point could be cached away somewhere and retrieved—it feels very much like a violation of the system, in terms of testifying against yourself, because in this case the process is automatic.

These issues that we’re fascinated by are one part of our show. We presented our show as science fiction in the beginning—but, it turns out, maybe not as fictional as people would hope. Another science fiction component that we’re exploring in the second half of this season is the artificial intelligence of it all. We took the position that in this headlong, post-9/11 rush to prevent terrible things from happening, the only true solution would be to develop artificial intelligence. But if you were to deduce the motives of a human being, you would need a machine at least as smart as a human being. That’s really the place in which the show remained, to our knowledge, science fiction—we’re still a long way off from that. For the second half of the season, we’re exploring the implications of humans interacting with data as the data becomes more interactive.

Jonathan, you previously explored the idea of surveillance in The Dark Knight. How did you develop the system Batman uses to tap the cell phones in Gotham?

Nolan: The thing about a cell phone is it’s incredibly simple and it’s a total Trojan horse. Consumers think of it as something that they use—their little servants. They want a piece of information, they pull it out and they ask it. They don’t think that it’s doing anything other than that; it’s simply working at their behalf. And the truth is, from the government’s perspective or from private corporations’ perspective, it’s a fantastic device to get unbeknownst to the consumer. It’s recording their velocity, their position, their attitude, even if you don’t add Twitter into the mix. It’s incredibly powerful.

In The Dark Knight, riffing off of storylines from existing Batman comic books. There’s a shifting side to where he’s always playing on that edge of how far is too far. In the comic books, at least, he has a contingency and a plan for everyone. He knows how to destroy his friends and allies, should they turn into enemies, and he’s always one step ahead. In a couple of different storylines in the Batman comic books, they play with the idea that he would start constructing . In the comic books, it was mainly about spying on his friends and allies and the rest of the Justice League. But for us it felt more interesting to take existing technology and find a way someone like Bruce Wayne, who’s this brilliant mind applied to the utility belt. There are all these gadgets and utilities around him—why should it stop there? Why wouldn’t he use his wealth, his influence and his brilliance to subvert a consumer product into something that could give him information?

In the previous incarnations of Batman on film, it was usually the bad guys doing that—rigging up some device that sits on your TV and hypnotizes you and makes you an acolyte for the Riddler or whatever. In this one, we sort of continued the idea because Batman, most interestingly, is a bit of a villain himself—or at least is a protagonist who dresses like a villain. So he creates this all-seeing eye, the panopticon, which I’ve been interested in since I was a kid growing up in England, where they had CCTV cameras everywhere in the 1970s and 1980s.

would deploy those as a nuclear option in terms of trying to track down the Joker’s team, something that definitely spoke to the duality of the character. He does morally questionable things for a good end—hopefully. In The Dark Knight, as epic and long as it took us to make it, really only got to scratch the surface of this issue, the devil’s bargain of: What if someone built this for a really good, really singular purpose? What level of responsibility would they feel towards it, towards what they created?

It’s something you really hope the government is sitting around agonizing over. I hope the government spends as much time worrying about this as Bruce Wayne and Lucius Fox do in The Dark Knight, but I’m not 100 percent sure that that’s the case. Certainly if you look at the history of polity and the way that government interacts with checks and balances, you kind of need a crisis, you need a scandal, you need something to prompt this self-policing.

Plageman: Are you saying that the FISA court is a joke, Jonah?

Nolan: If it is a joke, it’s a joke on all of us. But again, we don’t want to sound unsympathetic. “Person of Interest” takes for granted the existence of this device and, potentially controversially, the idea that in the right hands, such a device could be a good thing. But I don’t think Greg and I or any of our writers are ever looking at this issue and reducing it to black and white.

We’ve occasionally read that the show is kind of an apologia for PRISM and the surveillance state, just as I had read, a few years ago, certain commentators looking at The Dark Knight and imagining that it was some kind of apologia for George Bush. All those ideas are ridiculous. We look at this show as a great mechanism for posing questions, not supplying answers. That’s where we hope it’s not didactic, and The Dark Knight was certainly not intended as didactic. I think where we were ahead of the curve when it came to “Person of Interest” was that the thing we were assuming was still a question for everyone else. We kind of started the show in the post-Snowden era, as you put it. The show’s premise is that the surveillance state is a given, and we’re not changing that, and you’re not stuffing the genie back in the bottle. So what do we do with all the other information? That I think will increasingly become the real quandary over the next 10 to 15 years.

Jonathan Nolan, Greg Plageman and Shane Harris will speak in a panel discussion on Friday, October 25, as part of the Lemelson Center symposium, “Inventing the Surveillance Society.” This event is free and open to the public. Seating is limited; first come, first seated.