How Soccer Is Changing the Lives of Child Refugees

Arrivals from war-torn countries find refuge at a Georgia academy founded by an immigrant

:focal(-91x-137:-90x-136)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/00/b9009afc-3113-46f8-ad30-03396cf6d4ec/15salazar-porziotroyanomanyvoicesvelasquezfig02.jpg)

The day after the 2016 presidential election was a stressful one in a school in Clarkston, Georgia. The students, all refugees from war-torn regions of the world, arrived in tears. Some of them asked, “Why do they hate us?” Hoping to reassure the students, soccer coach Luma Mufleh and the teachers held a special meeting to discuss the American political system. They explained that the American government, unlike those of the countries they came from, operated under a system of checks and balances that would review the president-elect's policies.

Though most middle and high school students would be familiar with this fundamentally American value, these students are recent immigrants, a status that puts them at the center of a political firestorm.

The students attend the Fugees Academy, a private school funded by the Fugees Family, a non-profit organization that Mufleh founded to support refugee children and their families in the Atlanta suburb.

Months have passed since that first post-election conversation and the topic of refugees continues to make headlines. Less than 24 hours after parts of President Trump’s “travel ban” went into effect, barring some refugees from entering the country, Mufleh and nine of her students traveled to Washington, D.C. to participate in the 2017 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, a theme of which focuses on youth, culture and migration. They presented soccer drills and spoke about their refugee experience in a story circle.

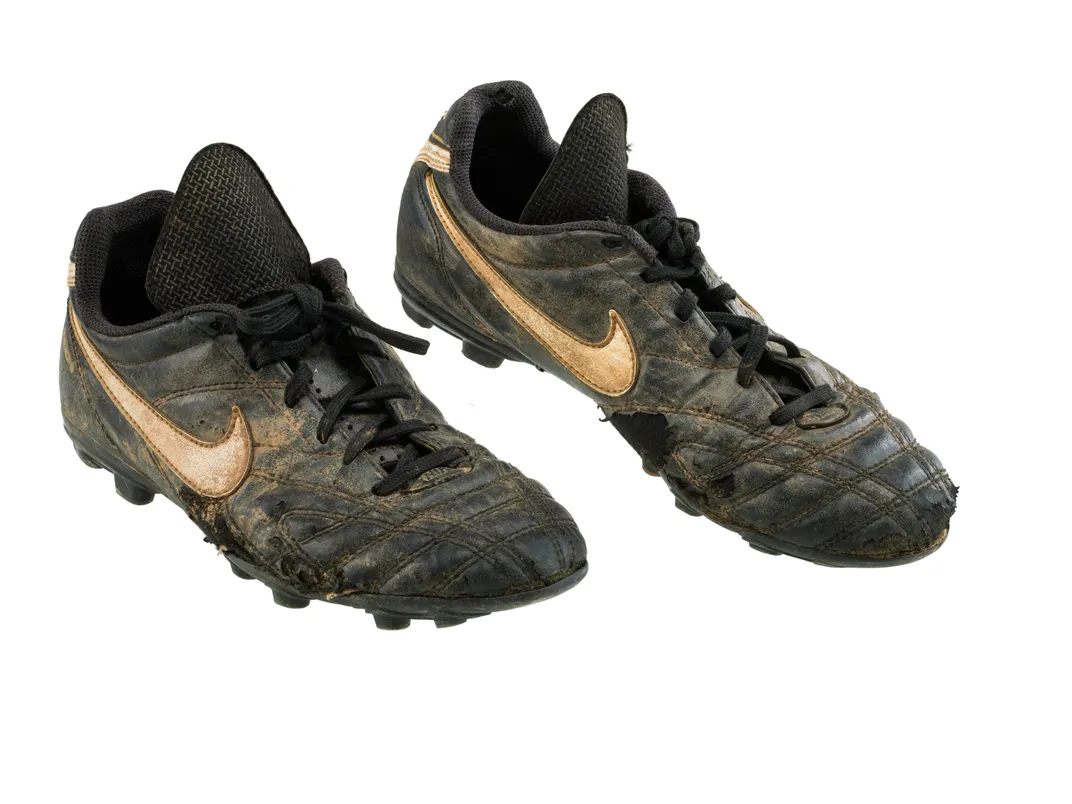

They also saw on display, for the first time, items from their soccer team, including a jersey, a soccer ball and a pair of cleats in the new exhibition "Many Voices, One Nation" now on view at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

The objects are located in the recently revamped and reopened second floor of the museum's west wing. The show's title evokes the sentiment of the Latin phrase e pluribus unum, which is found on the United States seal and roughly translates to “out of many, one.” Telling the centuries-long story of migration to the United States, the exhibition begins with the arrival of the Europeans in 1492 and follows the waves of migration through the early 2000s.

Some objects tell stories of cultural exchange, while others such as a Border Patrol uniform, reveal the legacy of measures to control migration. The imagery of the Statue of Liberty is prominent in the exhibition; most notably in the form of a paper mâché rendition used in a march demanding improved working conditions and higher wages for migrant workers.

The Fugees objects tell a slice of the particular migration story of refugee resettlement, and hint at the years Mufleh has dedicated to the refugees in her community. Mufleh arrived in the U.S. from her native country of Jordan in the mid-1990s to attend Smith College in Massachusetts.

After graduation, Mufleh moved to the suburbs of Atlanta where she opened a café that served ice cream, sandwiches and coffee. Though she lived and worked in the town of Decatur, she frequented a Middle Eastern store in nearby Clarkston, where she could find the authentic hummus and pita bread that reminded her of her home country.

But one afternoon in 2004, she took a wrong turn in Clarkston and found herself in the parking lot of an apartment complex where a group of young boys was playing soccer.

“They reminded me of home,” she says. Playing without referees or coaches and with a beat up ball, the scene was reminiscent of the streets where Mufleh played with her brothers and cousins. So compelled by these children, she hopped out of her car with a nicer ball and convinced the boys to let her in on the game. She soon learned they were refugees from Afghanistan and Sudan, and she bonded with them over their shared identity as Muslim immigrants.

Throughout the next few months, she continued to play soccer with them—some of them barefoot and using rocks as goal markers. Later that year, she founded an official competitive soccer team made up of refugees. They called themselves the “Fugees,” as in refugees.

But she soon realized that soccer alone could not address the many issues refugee children face. Upon arriving in the United States, these children are frequently enrolled in age-appropriate classrooms without consideration of their education level. Some of them, such as those from Syria and Iraq, have not attended school in several years due to conflict in their home countries. Others, such as those born in refugee camps in Ethiopia or Myanmar, the country also known as Burma, have never been to school and are illiterate even in their native languages.

“They’re expected to do algebra when they’ve never set foot in school and they don’t know how to add or multiply,” she remarks.

She began the Fugees Academy to educate students, no matter how far behind they are. Offering classes for sixth through twelfth grade, the academy has become so popular among the refugee community that Mufleh receives nearly three times as many requests for enrollment as she has space and resources.

But though the Fugees Family’s reach has expanded far beyond the soccer field, they’ve never neglected their roots in the sport. She and her staff coach several teams, some of which compete in a recreational league while the others compete in an independent school league.

“Soccer is the one thing that’s very familiar to them and the one thing that is normal,” she says. “It reminds them of home.”

In conversation in the days leading up to their demonstration at the Folklife Festival, Mufleh said she hoped the students would share their unique stories while reminding those who attend that they are not just refugees. They are children and adolescents, first.

“They’re just like most kids,” she notes. “Yes, they’ve had experiences that children typically don’t have. But they have so much to contribute to this country to make it great and to teach us all about how grateful we are to be here.”

"Many Voices, One Nation" is now on view at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian's 2017 Folklife Festival continues on the National Mall July 6 through July 9, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)